"WE" Pluribus Unum

Despite all our differences, Americans need to recover the power of “we.” And today is a little-known Jewish holiday that can help us to do just that.

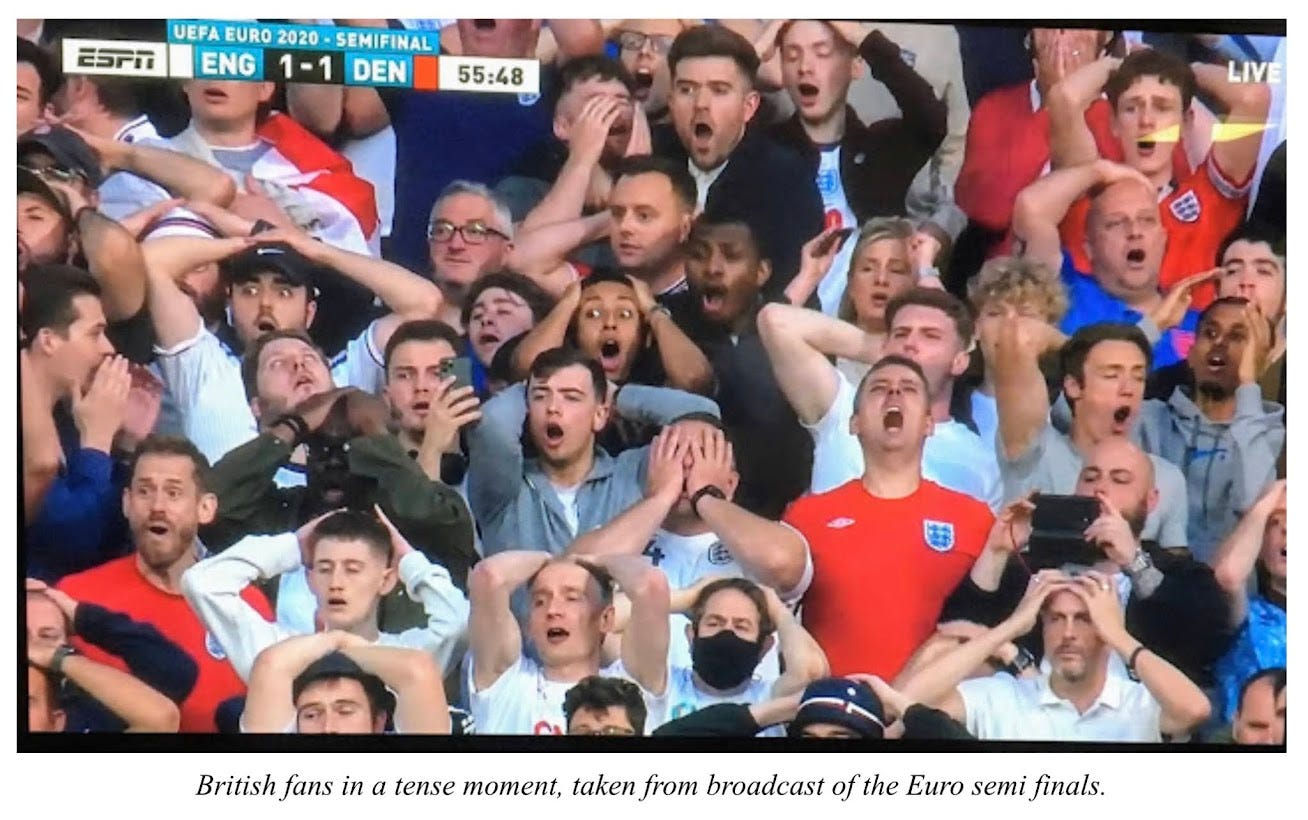

Back in 2020, I took this screen grab of a group of English fans after a near-miss against Denmark in a Euro soccer match.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, this one gives us a thousand ways to express absolute agony…except for that one guy in the glasses, who is either frozen in disbelief or a Danish fan in the wrong section - and why is he the only one wearing glasses? Each face tells a story - a different story about the same thing, the same shared pain.

Agony is agony, but there is something very comforting about it being “our” agony and not just my own, to be sitting among thousands who know exactly how we feel, who will be there to comfort us afterwards.

Sharing life’s roller coaster ride is important, but so is sharing responsibility when the ride is over.

The Talmud states (Shabbat 54b):

"Whoever can stop the people of his city from sinning but does not is responsible for the sins of the people of that city. If that person can stop the whole world from sinning and does not, they are responsible for the sins of the whole world."

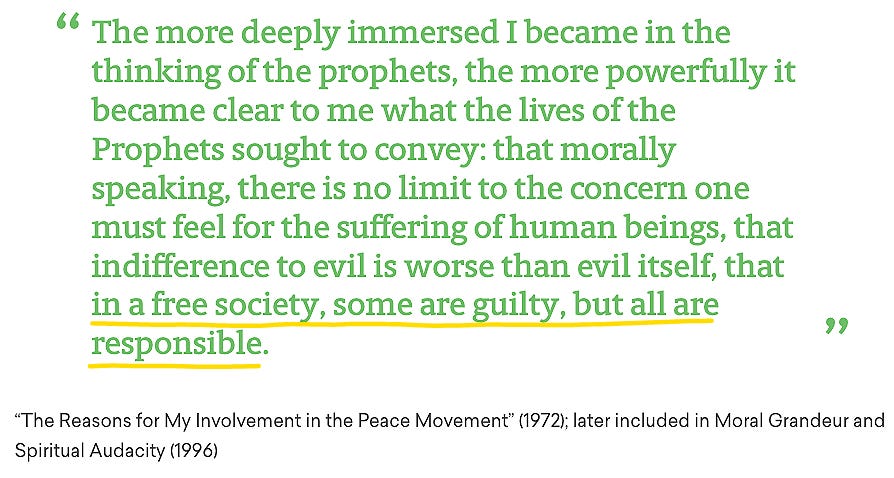

The rabbis felt that each of us, with each deed, can tip the scales one way or another, for ourselves and for the world. We are utterly and hopelessly interdependent and responsible for the actions of those around us. Not just for all Jews, but all of humanity. As Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote:

Another Talmudic verse, which does speak specifically about Jews, states, (Shevuot 39a):

"All Jews are responsible for one another."

The word for "responsible" here, ay-ruvin, means to stand in one's place, as surety, the way Judah was willing to become a prisoner in Benjamin's place in the Joseph story. It points to our interlocking fates.

On Yom Kippur, Jews repent in the first person plural. The sins of one are the sins of all, and the destiny of one is the destiny of all. In fact, nearly all of the standard liturgy is written in the plural, directed to a singular God “You,” from a collective, “We.”1

Why? Because, as Sharon Weiss-Greenberg writes:

Plural language in prayer helps to invoke a sense of collective responsibility. No matter whether we’re praying alone or in community, we are prompted to think about the whole of humanity when we pray, not only of ourselves.

We can achieve harmony with multiple tracks

And at this fraught moment in American history, that’s how we have to be thinking. Despite all our differences, Americans need to recover the power of “we.”

In my last posting, I called for boldness in standing up to the threats to our democracy and world order, saying that “the time for opinions has passed. It’s time for Burning Conviction. It’s time to counter Big Lies with Big Truths.”

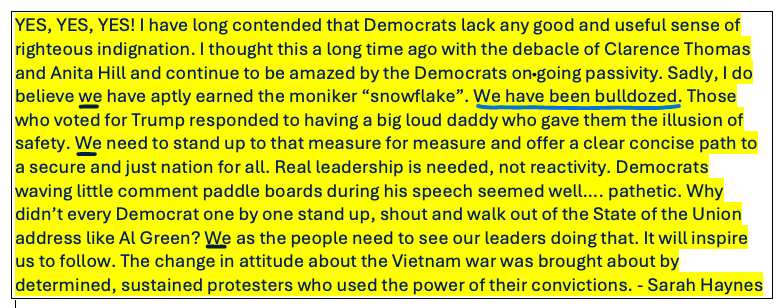

A reader replied by expressing the frustration we’ve been hearing from many Democrats this week:

I replied to Sarah that, as important as her ideas were to share, I was most impressed that she made her point so powerfully without personal attacks - and in fact she included herself when she wrote, "We have been bulldozed" and “we” have earned the moniker snowflake and need to stand up to that. The operative word is “we.”

So much of what we heard last week, which has been coming to a head since the election, was the blame game. In some ways an “autopsy,” can be helpful, and we’ve seen countless attempts at that coming from all sides, many on display in this week’s Economist. “After any major loss,” the article states, “political parties often go through a warring-factions period.”

Today’s autopsy by Ezra Klein in the Times is also helpful. In claiming that right-wing populism thrives on scarcity and that progressives have failed at providing abundance, he then advises the Democrats, “If they are going to marginalize MAGA, they need more than a resistance; they need new answers that admit past failures.”

As a journalist, it’s appropriate (though old school) for him to not utilize the language of “we,” but it also lacks the humility of Sarah’s comment, and fails to acknowledge the complexity of the question. True, it is more expensive to live in some states than others, but is that really why Trump won, when other Democrats won down-ballot in those same states? And didn’t Biden’s legislation provide an abundance of goodies for the middle class?

Is the root of Trump’s victory the cost of living? Excessive wokeness? Passivity? Apathy? Big Money? Corrupt judges? Russia? Racism?

And is the solution to aim for the middle? The left? Roll over and play dead, as James Carville would have us do? Take to the streets? Go to Trump’s speech in Congress? Boycott it? Walk out? Play nice with his supporters? Excoriate them? Genuinely listen to them? Or all of the above?

Respectfully, we don’t have time for warring factions to sort things out. The kind of blame game we’re seeing does not help Democrats, but more to the point, it does not help America.

That little turn of phrase, taking “they” and turning it to “we,” THAT is what can make all the difference.

Say “we” and we immediately understand that having a big tent isn’t just about ends, but means. It’s both a strategy to be inclusive and unifying, as well as the ultimate goal.

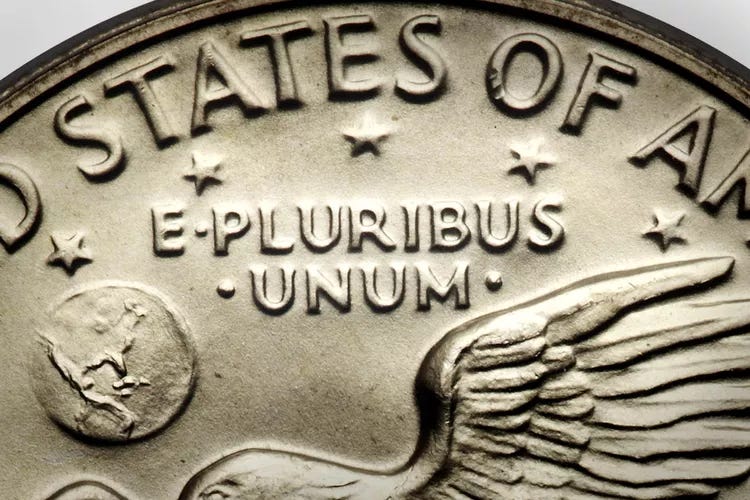

But unity of means does not mean uniformity. Rep Green got into “Good Trouble” last week, and Senators Murphy2 and Sanders turned up the volume, while ten Democrats, voting against Green, tried to preserve at least the illusion that we live in a rule-based world. I’m fine with all of it, even though it seems contradictory, but a Big Tent allows for people to have different approaches. For what does E Pluribus Unum mean but “From Many, One.” We need many approaches - judiciary, legisltative, grass roots, Good Trouble and Good Boy (and Girl) Scout - to get to that ultimate goal of being a truly United States, perhaps for the first time. We can achieve harmony with multiple tracks.

And “we” also includes Republicans.

We know that lots of people split tickets in swing states like Michigan, Wisconsin, North Carolina and Arizona. The Wall Street Journal reports that sixty-nine percent of Republican voters who support President Trump consider Russia an aggressor, while 83 percent do not support Vladimir Putin.

“Contrary to stereotypes, Republican voters have nuanced views about America’s place in the world and Russia’s war. Their opinions on Ukraine are considered, internally coherent and broadly well-informed,” the report states.

That is not a prescription for a campaign of “us vs. them.”

The path to reunifying the Democratic party, and ultimately most Americans is through a singular message above all - and that message is E Pluribus Unum3.

It can be done.

Say “we” and we immediately understand that having a big tent isn’t just about ends, but means. It’s both a strategy to be inclusive and unifying, and it’s the ultimate goal. But unity of means does not necessairly imply uniformity.

A little-known Jewish holiday

Today in the Hebrew calendar is Adar 9, a date that has a peculiar and not well-known place in Jewish history.

Adar 9 is the day on which approximately 2,000 years ago, the initially peaceful and constructive disagreements between two dominant Jewish schools of thought, the Houses of Hillel and Shammai, turned destructive over a vote on 18 ideologically charged legal matters4, leading, according to some sources, to the death of 3,000 students. (And you think things are bad now!) The day was said to be as tragic as the day the golden calf was created. Today some Jews observe the 9th of Adar as a day to explore the potential of constructive conflict to strengthen relationships, communities and societies.

Why don’t we all take a little time out of our contentious lives to do that today? The 9 Adar Project of the Pardes Institute gives us some recommendations on how to promote constructive dialogue. I’m sharing two guides from the institute, one explaining the day and the other with rabbinic source material. And below that, some advice from Pardes, based on the Moral Foundation Theory of Jonathan Haidt:

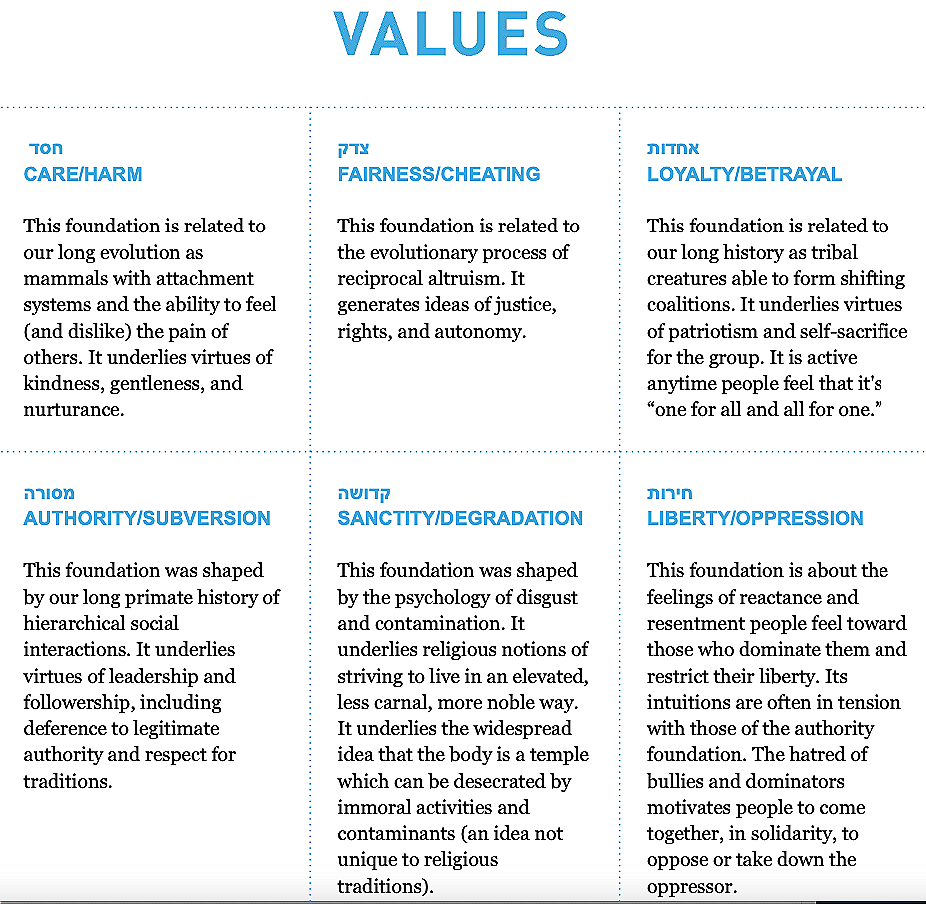

One of the most effective ways of fostering a more productive style of dialogue, is to reframe the way we see each other. Rather than simply labeling and judging those with whom we disagree, social psychologists like Jonathan Haidt offer a tool that can help us see each other in a more nuanced way. These social psychologists argue that all people are born with six innate moral foundations or values, which they coined the Moral Foundations Theory. They argue that like tastebuds, these six moral foundations are something that all people share, however each value gets prioritized differently by each individual, depending on their particular life experience. By studying these six moral foundations (they’ve since added a couple more), we can approach a dispute with the necessary nuance and self-awareness that lends itself to healing broken discourse. We have listed these six values and paired them with their equivalent Jewish value (see the values below by clicking on the footnote5)

Here’s a video summing up the lessons of 9 Adar:

To get to “we” we need to have the courage to stand alone.

One more point.

There is so much to be gained in looking at our neighbors as part of an ever-expanding “we.” We are ultimately responsible for their sins, as they are for ours. We’ll all have to clean up the mess together some day.

But sometimes, in order to bring people together, it takes an incredible act of courage by individuals willing to stand alone. That’s the ultimate paradox here. In order to find comfort, real comfort, in unity, it will take a willingness to stand apart.

For Republicans, that needs to happen soon. Someone needs to say “enough is enough,” regarding Elon Musk, or the cruelty toward immigrants or LGBTQ - or transgenic mice, for that matter. It means brushing aside the ferocious bullying and political pressure Trump applies6. But most likely, and most urgently, it will be about Ukraine and Russia. Someone will have to pull a Howard Beale and not take it anymore.

But it needs to happen for Democrats too, for whom standing apart for the sake of unity might just mean not getting quite so pissed every time someone with the best intentions doesn’t handle things the way you would. It might just mean not repeating blindly something someone angrily said on a podcast and thereby follow the herd off the cliff.

I close with a quote from someone who knew how to stand alone when the moment demanded it, whose legacy is now being tarnished by his namesake.

In 1966, Robert F Kennedy said this in apartheid Cape Town to a group of South African students.

“Let no one be discouraged by the belief that there is nothing one person can do against the enormous array of the world’s ills, misery, ignorance and violence. Few will have the greatness to bend history, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events. And in the total of all those acts will be written the history of a generation. It is from numberless, diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a person stands up for an ideal or acts to improve the lot of others or strikes out against injustice, he or she sends a tiny ripple of hope. Crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples can build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

Listen to this speech: 7

There is no better way for us to bring our community, our nation and our world together than by pledging to have the courage to, when necessary, stand alone.

May this be a meaningful Adar 9 for us all.

See MyJewishLearning: Why do Jews pray in the plural? Sefer Hasidim, a 13th century work of teachings about the practices of German Jewry, explains that prayer was instituted in this way because God only listens to the requests of those who are also conscious of their fellows’ needs. This idea echoes a comment Rashi makes on the talmudic discussion about Tefillat Haderech: We pray on behalf of others to increase the chances that our prayers are answered. Plural language in prayer also helps to invoke a sense of collective responsibility. No matter whether we’re praying alone or in community, we are prompted to think about the whole of humanity when we pray, not only of ourselves. Because the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, we pray in this way no matter where we are physically — both to improve the receptivity of our prayers and, perhaps, to deepen our empathy for others. Even when we do not sit in the same room or walk in another person’s shoes, still we pray for them.

Senator Murphy told the Hartford Courant in Sunday’s edition: (Connecticut’s senator leading national resistance against Trump: ‘We’ve got to flood the zone’)

There is obviously a debate inside the Democratic Party. There are some people who want to sit back and wait for Trump to fumble and then activate when the moment is right. I do not subscribe to that model of using and exercising power. I think (Republicans) flood the zone every day, and we've got to flood the zone. I think people won't trust you if you run a campaign saying that if Donald Trump is elected, he's an existential threat to democracy, and then you retreat. If he's such a threat to democracy, then you need to be fighting every day.

Some history of E Pluribus Unum:

The U.S. Continental Congress first proposed the motto E Pluribus Unum in 1782, for use on the Great Seal of the United States. Gentlemen's Magazine, an important men's magazine published in England beginning in the early 18th century, is thought to be the immediate inspiration for the term. The magazine was extremely influential among the intellectual elite; every year, it would publish a special issue comprised of the best of the year's articles. E Pluribus Unum appeared on the magazine's title page to explain that the publication became "one issue from many previous issues."

Pierre Eugene du Simitiere originally suggested E Pluribus Unum as a motto in 1776. Historically, several significant authors used the phrase or a variant of it. The motto's early sources are thought to be a poem attributed to Virgil, Confessions by St Augustine, Cicero in his De Officiis, and several other pieces of writing. Given its rich history, it's appropriate that the U.S. founding fathers chose this to be our motto. (It no longer is, since 1956, when it was replaced by “In God We Trust.”)

Fun Facts

Just as the U.S. has thirteen original colonies, E Pluribus Unum has thirteen letters.

The phrase ex pluribus unum goes back to ancient times, and Saint Augustine used it in his c. 397-398 Confessions (Book IV.)

It has been used by the Scoutspataljon, a professional infantry battalion of the Estonian Defence Forces, since 1918.

E Pluribus Unum still appears on U.S. coins even though it is no longer the official national motto! The United States Congress gave that honor to In God We Trust in 1956 by an Act of Congress (36 U.S.C. § 302).

In the 1939 film The Wizard Of Oz, the Wizard gives the Scarecrow a Diploma from The Society of E Pluribus Unum.

E Pluribus Unum was first used on the 1795 Liberty Cap-Heraldic Eagle gold $5 piece.

Read all the details about those 18 laws and what happened that day in this account. It was a nasty power grab by the School of Shammai, not unlike what’s happening today. If you are really interested and have a little background, you can hear all the details in this lecture:

Values chart for constructive dialogue, followed by an updated listing from Moralfoundations.org

Care: This foundation is related to our long evolution as mammals with attachment systems and an ability to feel (and dislike) the pain of others. It underlies the virtues of kindness, gentleness, and nurturance.

Fairness: This foundation is related to the evolutionary process of reciprocal altruism. It underlies the virtues of justice and rights.

Loyalty: This foundation is related to our long history as tribal creatures able to form shifting coalitions. It is active anytime people feel that it’s “one for all and all for one.” It underlies the virtues of patriotism and self-sacrifice for the group.

Authority: This foundation was shaped by our long primate history of hierarchical social interactions. It underlies virtues of leadership and followership, including deference to prestigious authority figures and respect for traditions.

Purity: This foundation was shaped by the psychology of disgust and contamination. It underlies notions of striving to live in an elevated, less carnal, more noble, and more “natural” way (often present in religious narratives). This foundation underlies the widespread idea that the body is a temple that can be desecrated by immoral activities and contaminants (an idea not unique to religious traditions). It underlies the virtues of self-discipline, self-improvement, naturalness, and spirituality.

In our original conception, the Fairness foundation was skewed toward concerns about equality, which politically left-leaning individuals more strongly endorse in different cultures. In 2011, based on new data, we emphasized proportionality, which is often endorsed by everyone, but is slightly more strongly endorsed by politically right-leaning people. In 2023, based on a decade of empirical work, our team led by Mohammad Atari decided to split the Fairness foundation into Equality and Proportionality, making the case for six main foundations (Atari et al., 2023):

Equality: In our theoretical reformulation of MFT in 2023, we defined Equality as “Intuitions about equal treatment and equal outcome for individuals.”

Proportionality: In our theoretical reformulation of MFT in 2023, we defined Proportionality as “Intuitions about individuals getting rewarded in proportion to their merit or contribution.”

Since MFT was first described in 2004 (Haidt & Joseph, 2004), we have tried to identify the candidate foundations for which the empirical evidence was strongest. We proposed five criteria for foundationhood (Graham et al., 2013): (a) being common in third-party normative judgments; (b) automatic affective evaluations; (c) being culturally widespread though not necessarily universal; (d) evidence of innate preparedness; and (e) a robust pre-existing evolutionary model. We think there are several other very good candidates for “foundationhood,” especially:

Liberty: This foundation is about the feelings of reactance and resentment people feel toward those who dominate them and restrict their liberty. Its intuitions are often in tension with those of the authority foundation. The hatred of bullies and dominators motivates people to come together, in solidarity, to oppose or take down the oppressor. In 2012, we reported some preliminary work on this potential foundation, on the psychology of libertarianism and liberty (Iyer et al., 2012).

Honor: This foundation is about one’s self-worth based on their reputation and assessment of what others think. In 2020, we made the case that honor (more accurately, “Qeirat” in Middle Eastern cultures) can be an additional foundation wherein a man is expected to protect his kin and family, and under some circumstances, be ready to violently retaliate against anyone who insults his family’s reputation (Atari et al., 2020).

Ownership: This foundation has been on the radar of moral psychologists for a long time, and yet it remains one of the least studied constructs in this literature. In 2013, we maintained the importance of ownership as an additional foundation.Ownership intuitions are “fast” and it is ubiquitous in human societies. Human intuitions about ownership have obvious parallels in other animals, and respect for property is an evolutionarily stable strategy. In 2023, we argued that Ownership may meet the entire set of criteria to be an additional foundation (Atari & Haidt, 2023).

The theory was first developed from a simultaneous review of current evolutionary thinking about morality and cross-cultural research on virtues. The theory is an extension of Richard Shweder’s theory of the “three ethics” commonly used around the world when people talk about morality (Shweder et al., 1997.) The theory was also strongly influenced by Alan Fiske’s relational models theory (see Rai & Fiske, 2011)

Here (attached below) is some fascinating background to this RFK speech from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s memoir, An Unfinished Love Story:

No comments:

Post a Comment