"Maybe Jesus will save her from those Buddhists!"

Eastern spirituality grabbed center stage in "The White Lotus" and there was no chaplain in "The Pitt." But as Passover & Holy Week arrive, the faiths of Jesus and Moses still share powerful messages.

Yep. Spoilers ahead.

With Holy Week and Passover upon us, let’s take a look at two HBO series that have monopolized conversations at water coolers both real and virtual this month - The White Lotus and The Pitt, both of which celebrate spirituality in their own way while giving short shrift to what people call “organized religion.”

Spiritual, not Religious

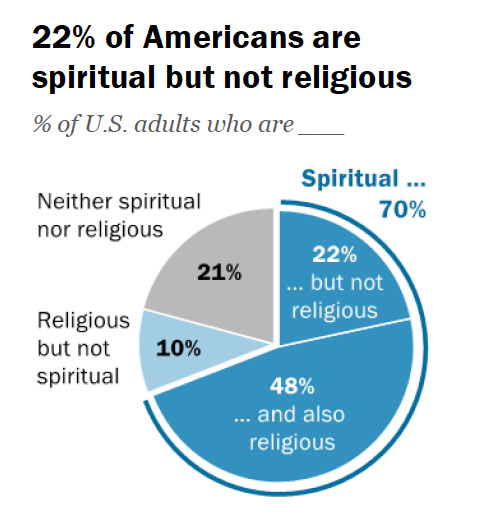

Let’s begin with a key question: Is there a difference between “spirituality” and “religion?” I’ve spent decades trying to prove that there isn’t. Apparently not everyone agrees. See this Pew survey from 2023.1

I can recall how years ago, the theologian Arthur Green wrote of his dismay over a personal’s ad written by a woman who described herself as a "DJF, 34. Spiritual, not religious."

What does that even mean?

It means that this divorced Jewish female felt alienated from her place of worship and may have been turned off by membership dues or a bad experience with clergy. But no doubt she felt uplifted by a walk along the shore and was outraged by injustice and cruelty. She undoubtedly felt a deep connection to the world around her - and beyond her - which in my mind means she was quite religious.

We in the religion biz have long had a bad image problem. But while mainstream faith groups bicker and back-bite and fail to be welcoming and inclusive, there is an unquenchable thirst for meaning out there. There's passion for encounters in nature. There’s a passion for morality. For a purpose-filled life. And for God. That may be spirituality, but in my mind it’s also religion.

So why does popular culture still have so much trouble with organized religion in America? Unless of course, the rabbi is hot and dating Kristen Bell.

Of Thais and Tides

I suppose that if The White Lotus is to be believed, we prefer our gods to be bald, pudgy, half naked and ascetic and to take our families halfway around the world to see them. But in the end, the message from the Buddhist monastery is not that different - in its essence - from the one we get in that dusty building right here in America, right down the street.

Yes, Victoria, your daughter Piper Ratliff was saved from the Buddhists, though not by Jesus so much as her own addiction to a comfy bed and central air. But the key question of the final installment of The White Lotus’s third season, for Piper and the whole cast, was who will save them from themselves? Will their grounding in faith - to the extent that they had one - buoy them as they navigate the churning waters of temptation, jealously, greed, vanity and rage? For almost all of them this season, the answer was no, but seeds of redemption were planted for those that survived.

Piper was saved, then, not by Jesus, then but by her own vanity. And to add insult to injury - when Lochlan, the youngest son, claimed that he thinks he “saw God” in his near-death experience in the final episode, the divine being he imagined as he gazed, submerged in the hotel pool, looked suspiciously like the Buddhist monks that he had just encountered. Not Jesus. Not Abraham. Not Morgan Freeman and not George Burns.

It was left to Belinda’s son Zion, the last-minute interloper into the cast (whose fling with Piper was unfortunately left on the cutting room floor), to invoke the Christian deity when pleading for his mother’s safety as he heard gunshots being fired. But even that happened only while he was looking up at a statue of the Buddha. He then cursed at the idol2.

For a season where spiritual themes reigned supreme, Jesus had the smallest of bit parts - primarily as the defender of Victoria’s and Kate’s status quo of wealth and entitlement3 and as Zion’s last resort. Other Abrahamic faiths didn’t fare any better. I don’t think Jesus, Moses and Mohammad would have been happy to be cast in the role of temple moneychanger or a shill for tax breaks for billionaires in an Austin megachurch.

Lots of mixed messages here about faith, but the characters’ infatuation with Eastern religion was not so much a failure as a missed opportunity, a blown chance to see in their own faith traditions the same things they were seeking elsewhere.

I’m a big fan of Buddhism, but if only the suicidal Tim had a minister back home he could have contacted. That minister would certainly have already known about Tim’s financial scandal and - if it were me - would have been trying to reach him. If only Rick had had a way to process his grief over his father. If only Kate, the country club wife from Texas, had found more from her church than validation of her wealth and MAGA conversion, she could have found better ways to support her friends than by gossiping about them.

Religion - that old time religion - could have provided that way.

I suppose that if The White Lotus is to be believed, we prefer our gods to be bald, pudgy, half naked and ascetic and to take our families halfway around the world to see them. But in the end, the message from the Buddhist monastery is not that different - in its essence - from the one we get in that dusty building right here in America, right down the street.

The (Pul)-Pitt and the Sh’ma

Meanwhile, in the excellent new medical series, also on HBO-Max, “The Pitt,” which depicts with life-and-death realism a Pittsburgh emergency room, profound questions abound. In a moment of extremis, the main character, Dr. Michael Robinavitch, played by Noah Wyle, muttered a central Jewish prayer, the Sh’ma.

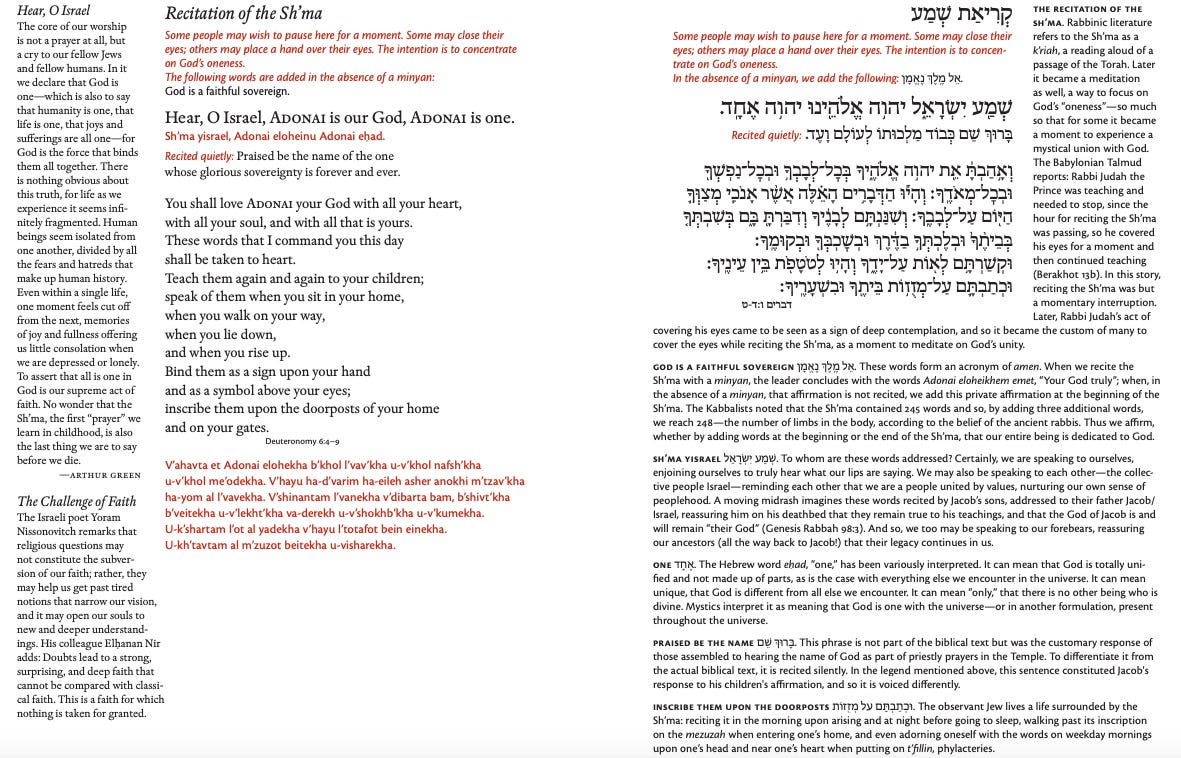

Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, The Lord is One4

When the most extreme moment of the entire series demanded an ancient and powerful response, Dr. Robby (who could pass for a rabbi in name and appearance, probably not an accident) knew the Sh’ma by heart.

But when he realized his “lapse” was being watched, he told another character, apologetically - with an acute embarrassment that he carried with him through the end of the final episode - that he was reciting it only because he had spent lots of time in his childhood with a religious grandparent.

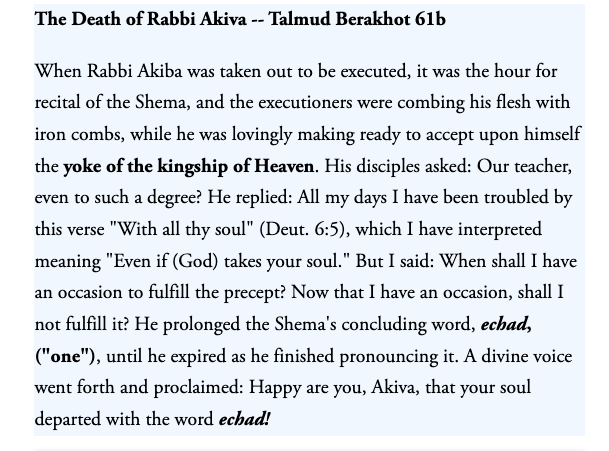

What he may not have realized is that his gut reaction it was the right response. The Sh’ma plays many roles in Jewish tradition, but one of them is that it serves as a “last rites,” a deathbed confession and declaration of faith, recited either by those dying or on behalf of those recently deceased. This prayer has been on the lips of martyrs for two thousand years, following the example of Rabbi Akiva.5 Robby was, in effect, reciting last rights for the shooting victims alongside him in that makeshift morgue. It was a cleansing, healing moment - but treated by other characters, and Robby himself, as a mental breakdown.

I can’t emphasize enough how incredible that moment was. The most cathartic scene of the most powerful medical series ever, centered around a prayer and a ritual that I’ve performed with the dead and dying hundreds of times. And yet, in The Pitt, where first responders routinely display raw emotion and are provided unlimited transfusion bags filled with grace - somehow this moment of totally appropriate religiosity was treated as a panic attack, “a complete meltdown” in Dr. Langdon’s accusatory words.

Other than that, the mainstream religious community is primarily absent from this series. How can a place where so many lives are on the line every day not have a chaplain? Even during a mass shooting crisis? There were more rats in that E.R. than clergy. A rabbi in the room could have recited the Sh’ma with Robby and helped him process his enormous grief.

Someone should tell that administrator who keeps threatening to shut things down. Don’t run from religion! Many emergency rooms have chaplains.

The only time clergy were called in was at the request of a patient to discuss organ donation. That was handled well by all parties. But so many opportunities were missed to apply timeless wisdom to contemporary crises, to learn from teachers like Rabbi Simkha Weintraub, who wrote in the periodical Sh’ma, “Our generation, as those before and after us, will be judged by how we listen to those who are sick and vulnerable and to those who care for them. In the end, there is no them. There is only us."

Moses, Jesus and Mohammad

For those kvetching about how Moses, Jesus and Mohammad seem to have no place in two profoundly spiritual shows, maybe we’re looking at things the wrong way. Maybe those shows - and they are excellent - are reflecting a societal bias against institutional religion, preferring other instruments of salvation, be they spiritual or secular. Who needs Western religion when you have a spiritual feast from the East, and who needs a chaplain in a hospital when you have a highly skilled social worker?

Interestingly it must be added that White Lotus included, of all things, a hit Jewish song that evidently is very popular in Thailand. Not only that, but Thais seem to think they invented it!6

That’s a great lesson for us. Jesus and Moses need not fret, because everything that seems to be unique to Eastern spirituality in this White Lotus season can actually be found in our own Western traditions.

And everything brought to the table by the mental health professionals and caring first responders of The Pitt, the compassion they show for the living, the dying and the dead, has its roots in those very same traditions.

The social worker in the show is great. It’s just that a trained chaplain could have provided a manner of care that combines needed handholding with deep wisdom and the perspective of eternity.

To give you some examples, below is a packet filled with Jewish sources regarding the commandment of “Bikkur Holim,” visiting the sick.7

If I were to start a curriculum for rabbis on how to care for the sick, however, I’d start by assigning them to watch the full first season of “The Pitt.”

The Ocean and the Wave

The prevailing metaphor for life and death in this season’s White Lotus is the notion that each of our lives is like a drop of water8 which flies upward, but then we die, our drop becomes one with the Ocean again (see it on this video about 1:40 in). A similar metaphor that I’ve often encountered is that each individual is a wave crashing against the shore, which then receding back into an ocean of Oneness.

These beliefs are not unique to the religions of the East, nor are they fully representative of Buddhism’s approach to the afterlife9. They are found in the Abrahamic traditions too.

In other words, Piper (I can’t say it without imagining her mother saying “PAH-Purr”) didn’t need to go to such extensive (and expensive) lengths to drag her family to Thailand to learn that lesson. It could be found back in her classroom at U.N.C. or in her local church pew. Jesus could indeed have saved her from the Buddhists because there is not that much difference in how the different faiths employ these same metaphors. He could have directed you to Psalm 77:19 or Matthew 14.

Jews and Christians have been dabbling in that wave-ocean imagery for centuries. Water is one of the prime metaphors used for God in the Hebrew Bible.10

And so have Muslims. The great Sufi mystic Rumi wrote, “You are not a drop in the ocean. You are the entire ocean in a drop.”

I am in a boat made of myself by myself, no light and no land, I try to stay just above the surface, yet I'm already under and living with the ocean.

When you surpass the human state, your angelic nature will unfold beyond this world. Surpass the angels then enter that timeless ocean.

In his 1970 book Morality and Eros, Rabbi Richard Rubenstein wrote a passage that has influenced my own thought greatly:

God is the ocean and we are the waves. In some sense each wave has its moment in which it is distinguishable as a somewhat separate entity. Nevertheless, no wave is entirely distinct from the ocean... The waves are surface manifestations of the ocean. [Even as] our knowledge of the ocean is largely dependent on the way it manifests itself in the waves.

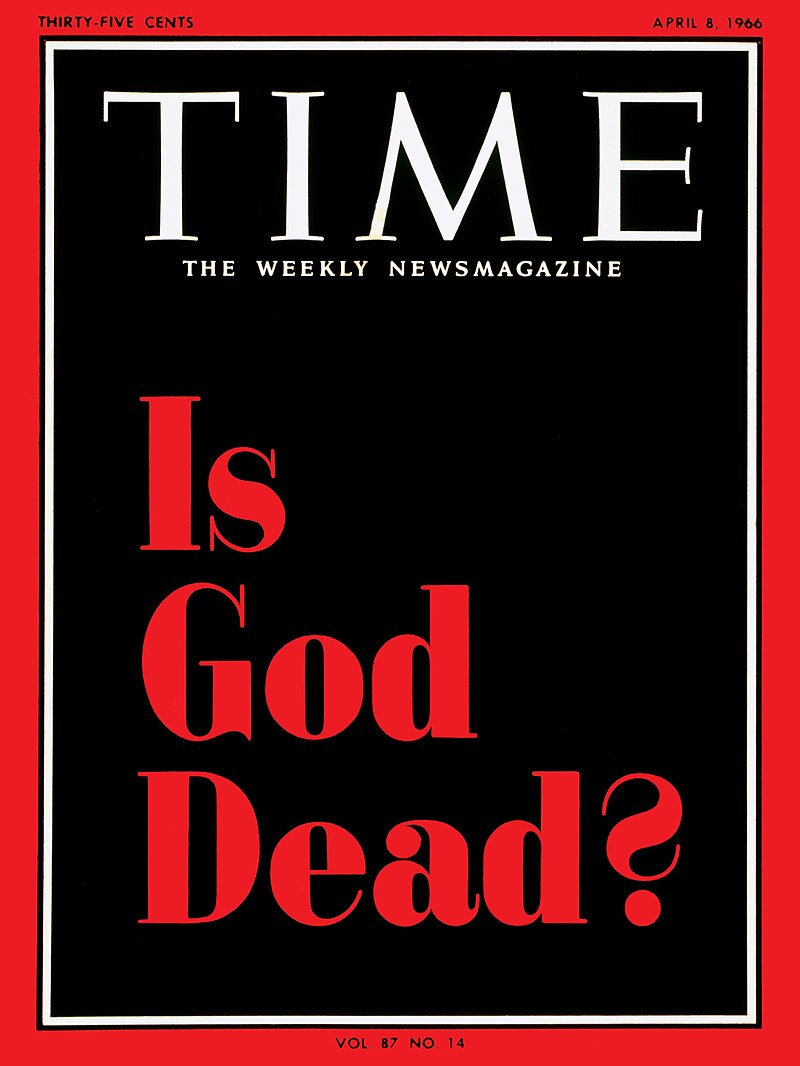

Rubenstein’s focus on that and other unorthodox metaphors drew the attention of Time Magazine following the publication of his book After Auschwitz in the mid-‘60s. That interview echoed Time’s classic cover story proclaiming the “Death of God” - meaning the death not of God but the traditional metaphors for God that had prevailed in Western thought for many centuries - until the Holocaust made them untenable.11

For a Christian’s perspective on this ocean imagery see this posting:

“They say that whenever the theologian Paul Tillich went to the beach, he would pile up a mound of sand and sit on it gazing out at the ocean with tears running down his cheeks. Maybe, what made him weep was how vast and overwhelming it was, and yet at the same time as near as the breath of it in his nostrils, as salty as his own tears.”—Frederick Buechner in Beyond Words (HarperOne, 2009).

Speaking of oceans of Oneness, click on footnote 12 for some wisdom from Hinduism, where there is a belief that different religions are simply different paths toward the same spiritual goal. 12 I can definitely relate to that.

There is so much that different faith traditions share. Piper, as a religious studies student, could have taught that to her parents and siblings. Maybe someday she will.

Which brings me back to my original question. Given how exceedingly deep and spiritual all our traditions are, accumulating so many centuries of wisdom, is there really a difference between spirituality and religion?

It's easy to put down all these spiritual leanings as neo-pagan fads, which, like so many over the centuries, will have their day and depart. But as we saw in The Pitt, long after the fads have come and gone, people will still be chanting the Sh'ma in times of trouble. They just need to be reminded what our faith traditions stand for. Not incessant fundraisers or politicized governance meetings. Not timid sermons and frosty fellowship. But something much better. Something Piper might like and Robby might need.

For religion, whether Western or Eastern, all points us toward that same “ocean of divinity,” one wide and deep enough to guide us toward enlightenment, to include all images of God - and to be God.

A sweet Passover and blessed Holy Week to all who celebrate! May our world be filled with new light and renewed hope!

…a scene that was censored by India’s largest streaming platform.

Kate and Victoria’s similarities don’t end with their reliance on church affiliation for status. Their social circles actually intersect.

First paragraph of the Sh’ma, from Siddur Lev Shalem (click here for a larger version)

And here’s another excellent packet, if you are in the mood to go deeper.

See also this posting of Buddhist wisdom

See What ‘The White Lotus’ gets wrong about the meaning and goals of common Buddhist practices (The Conversation)

Water is one of the most common metaphors for God in the Hebrew Bible, and is used to convey a range of experiences: being nourished by life-giving rain; being swept along by a powerful river; joining in the flow of justice. Just as a body of water can buoy us, refresh us, and sustain us, it can also become fearsome in a storm and overwhelm us. This can be a powerful metaphor for our own experiences of the sacred. Sometimes we seek spiritual nourishment; we long to drink from Peleg Elohim—the “God River.” At other times we feel buffeted by the waves of our life’s ups and downs, and seek reassurance, as in the words of the prophet Isaiah: “When you pass through the Waters, I am with you.” Water is life-giving, essential, and powerful; sometimes beautiful and sometimes scary. Just like life. Just like God. (from Reconstructing Judaism)

Some Biblical water names for the Divine include:

Wells of Liberation – May’anei Hayeshua – מַּעַיְנֵי הַיְשׁוּעָה

Deep – Tehom – תְּהוֹם

Fountain of Living Waters – M’kor Mayyim Chayim – מְקוֹר מַיִם חַיִּים

Source/Wellspring of Life – Ain Hachayim – עֵין הַחַיִּים

Time wrote this about Rubenstein’s metaphor: Ocean & Waves. Rubenstein, who has an M.A. from Jewish Theological Seminary and a doctorate in psychology of religion from Harvard, expressed his disbelief in Judaism’s traditional deity in After Auschwitz, a collection of essays published in 1966. There he argued that Hitler’s Holocaust was deathly proof that the “transcendent, theistic God of Jewish patriarchal monotheism” was no more. Strongly influenced by the late Paul Tillich, Rubenstein nonetheless concludes that there is a “Holy Nothingness” as the source of all being. This Holy Nothingness is totally beyond human comprehension or categorization, and he compares its relationship with man to that of an ocean and its waves: “Each wave has its moments in which it is discernible and distinguishable as a separate entity. Nevertheless, no wave is really separate from the ocean, which is its substantial ground.”

For those interested in going deeper (you’ll get LOTS of extra credit!)….

“Holy Nothingness“ is what the medieval Kabbalsits called “En Sof.” The clearest explanation can be found in Rabbi Lawrence Kushner’s interview with Krista Tippett for “On Being,” where he says:

I think the best way to understand it, Krista, is to remind you of two Hebrew words that are in kabbalistic language much more important than their normal definitions. The first word is “yaish.” And it’s sort of untranslated. If you held my feet to the fire I’d say it translated as is-ness. Being-ness. And “yaish” refers to virtually everything in creation: anything that has a beginning or an end, that has the spatial coordinates, that has a definition, that is bordered by other things. And it’s not just material reality. I mean, love has a beginning, it has an end. Beauty can have a definition. And it’s not bad. It’s not something to be renounced. Anybody who has tried to live in the world knows that it is the world of yaish. You and I are yaish. Our microphones are yaish. The room, the city of San Francisco is yaish. Everything is yaish. Yaish is not bad. It’s only bad if you think that’s all there is.

Turns out there is only one thing that’s not yaish. It has no beginning, it has no end, it’s not bordered by anything, it has no definition, it has no spatial coordinates. You probably can’t say as much about it as I’m about to try to say. It is the opposite of yaish. It is called ein sof: without end. Literally it means nothing. But with a capital N. Because if I said it was something — you’ve got to stay with the logic here — if I said “something,” then you will say “oh, well, it’s next to another thing.” And the Kabbalists, being serious about logic also, they are very logical, say “No, the only way we can talk about this non-yaish thing is to call it no-thing or nothing.” And that becomes ein sof, and that has something to do with God, the source of everything of yaish.

Everything in the world is made of ein sof. Everything in the world is the wave of which the ein sof, or God, is the ocean. And our knowledge of the ocean is largely based on the way it manifests itself in the waves, that is, the yaish. So my closest I can come to learning about ein sof and God is by talking to you or looking at a tree or planting one.

See also: Was the Universe Designed? Drops in the Ocean (L Kushner)12

Speaking of oceans of Oneness, here is some wisdom from Hinduism, where there is a belief that different religions are simply different paths toward the same spiritual goal. Sitansu S. Chakravarti, wrote in "The Hindu Perspective" (1991).

Thus, although spirituality is a necessary quest for human beings, the religion one follows does not have to be the same for everyone. [...] The first Hindu scripture, the Rigveda, dating back to at least 4.000 years, says: "Truth is one, though the wise call it by different names." The Mahabharata, which includes the Gita, is replete with sayings meaning that religious streams, though separate, head toward the same ocean of divinity.

Thank you so much for your words. God bless you.

Once I start reading here, I can’t stop! Such beautiful writing thank you.

❤️☮️