Friday, the Rabbi Resigned...and Other Profiles in Courage for an Era of Outrage.

Looking for new champions of conscience to rouse us, we find an ex prime minister, an artist, Scott Pelley and other truth tellers raising the stakes from "Good Trouble" to "Disturbed Sabbaths."

Friday, the rabbi resigned.

Take a look at this news article found in the front section of the New York Times of Friday, April 18, 1930. The resignation of a single rabbi, no matter how famous, would hardly garner the interest in our day that Rabbi Fisher’s resignation did back then. If only principle and courage mattered as much now.

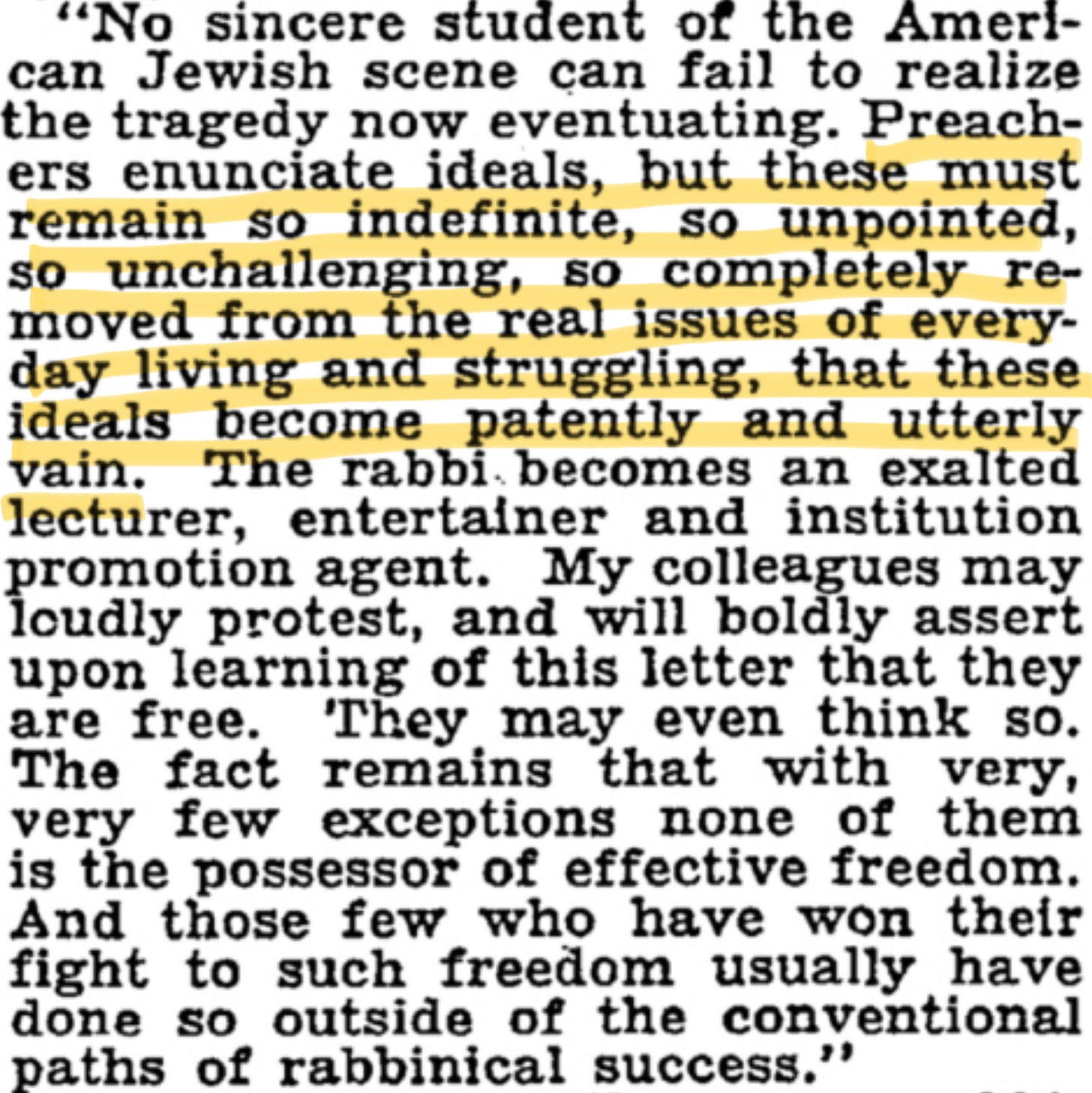

Here are some of the key passages in the article, and in particular his critique of the milquetoast, politically compromised and unduly compromising brand of religion he saw coming from the pulpits of America.

Here he gets to the point:

One wonders what Fisher was being fettered1 from preaching about. We know he was an ardent Zionist long before that was common in the Reform movement. He favored Socialists and saw the dangers of the Nazis - though in 1930 the specter of Hitler was not yet an enormous issue. He also called Prohibition a "national curse." But considering his recent ordination at that time, it’s hard to say that his resignation was triggered by anything other than pure youthful idealism and impatience at a time of political and economic upheaval.

This was a time of great upheaval, the early days of the Great Depression, when there was no shortage of supercharged rhetoric spewing forth from American pulpits, much of it hateful. Radio was still in its early days, but Father Coughlin, the most infamous antisemitic rabble-rouser of them all, signed with CBS radio that year for his first national broadcast. People could no longer afford the luxury of pretending things were OK, when soup lines were forming just outside the door. Like Jeremiah 8:11, Rabbi Fisher saw the need to call out those crying “Peace, Peace,” when there was no peace.

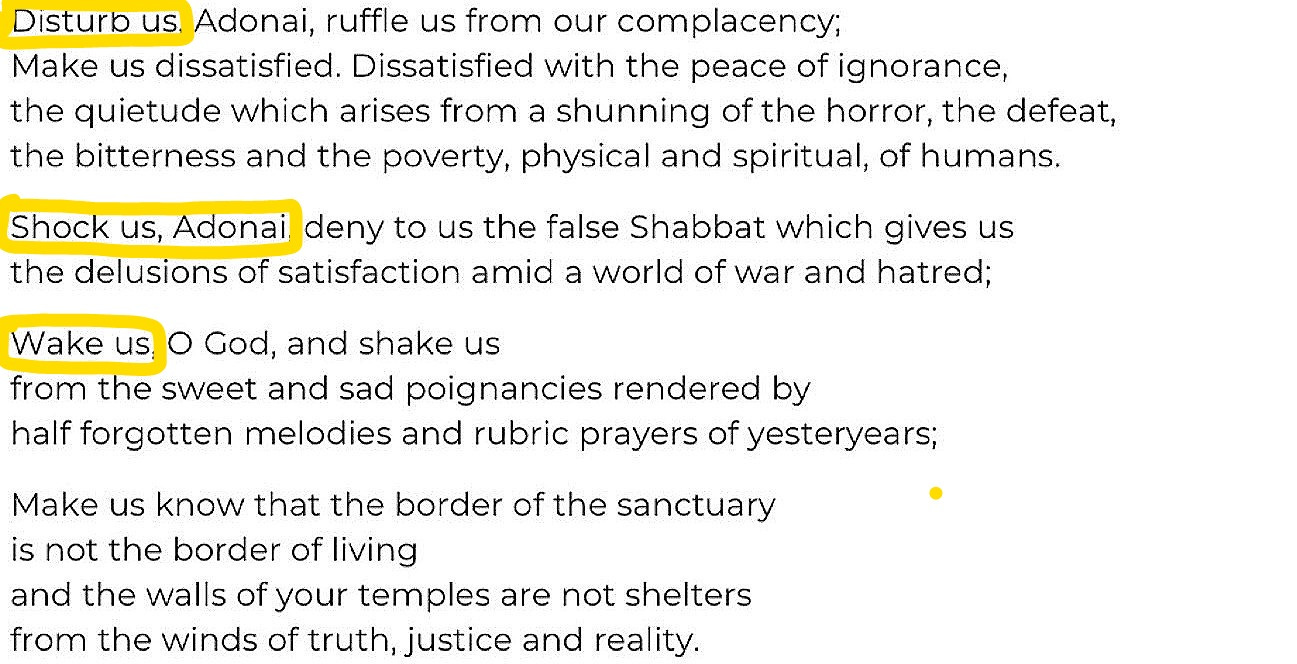

Perhaps the best clue as to Fisher’s agenda can be garnered from his “Prayer for a Disturbed Sabbath,” which much later found its way into the Reconstructionist and Reform prayerbooks.

John Lewis looked for “Good Trouble” in his day. Now we need to go one level higher and make sure that our Sabbaths are no longer restful. Whether on Friday, Saturday or Sunday, our Sabbaths need to be disturbing.

We don’t need rabble rousers. We need RABBI rousers. And other clergy rousers across the board. We all just need to be roused.

For rabbis like me, whose workplace is the word, we need to discover a new language to express our deepest concern over what far-right autocrats and extremist antisemites are doing to the countries we love most.

The word “Outrage” doesn’t begin to express the outrage we should be expressing.2 In his classic novel, See Under: Love, the great Israeli novelist David Grossman invents a language to try to communicate the horrors of the Holocaust. As he puts it, “We always pictured hell with boiling lava and pitch bubbling in barrels," until the Nazis came along, "showing us how paltry our pictures were."

We need to find new words. We can't fall back into cliches, and we can’t be so careful of inaccuracies that we become timid. We need to go from “Good Trouble” to “Heap’a Trouble!”

The Many Shades of Outrage

We look to role models of those who, like Rabbi Fisher, have demonstrated extraordinary courage,3 especially though not exclusively from the pulpit. With Israel’s recent overreach into Gaza, now covered in part by Israeli media, for the first time the outrage of many Israelis is beginning align with the rest of the world. 4

In New Jewish Narrative, Dina Kraft wrote this yesterday in her piece, For Israelis, Glimmers of Gaza’s Misery Begin to Penetrate a Wall of Silence:

In the almost 600 days since the October 7 attack, Zeev Engelmayer has posted on social media a color-drenched daily cartoon “postcard” of war-related pain and trauma. Until recently, most of the creations, painted in acrylics or drawn with felt-tip pens and signed “Shoshke,” Engelmayer’s pen name, depicted Israeli agony: The hostages and their families, and occasionally the bereaved and the displaced. But in recent weeks he has turned his brush and pen to the escalating Israeli attacks on Gaza dubbed “Gideon’s Chariots” that have left hundreds Palestinians killed, among them women and children. He has depicted the effects of widespread hunger in Gaza in wake of an Israeli blockade on food aid, now only partially lifted.

And here’s Shoshke’s own Facebook posting about recent killings of children in Gaza.

Shoshke is a folk hero in Israel. That posting took guts - and outrage.

And then this happened:

On Tuesday, the former prime minister of Israel, Ehud Olmert, came out in Ha’aretz and accused the current government of war crimes, an exercise in ballsiness that even Rabbi Fisher would admire.

Key excerpts from Olmert’s op-ed:

The government of Israel is currently waging a war without purpose, without goals or clear planning and with no chances of success. Never since its establishment has the State of Israel waged such a war. Recent operations in Gaza have nothing to do with legitimate war goals. The government sends our soldiers – and the military obeys – to wander around Gaza City, Jabalya and Khan Yunis neighborhoods in an illegitimate military operation. This is now a private political war. Its immediate result is the transformation of Gaza into a humanitarian disaster area….

Over the past year, harsh accusations were voiced worldwide against the Israeli government and its military's conduct in Gaza, including accusations of genocide and war crimes. In public debates in Israel and on the international arena, I've rejected such accusations firmly, though I didn't shrink from criticizing the government. The great number of innocent civilians killed in Gaza was hard to fathom, unjustified, unacceptable. But all, as I have said on every media outlet in the world, resulted from a vicious war.

What we are doing in Gaza now is a war of devastation: indiscriminate, limitless, cruel and criminal killing of civilians. We're not doing this due to loss of control in any specific sector, not due to some disproportionate outburst by some soldiers in some unit. Rather, it's the result of government policy – knowingly, evilly, maliciously, irresponsibly dictated. Yes, Israel is committing war crimes.

Olmert will be excoriated for this by many of his former supporters on the right. He will join the new leader of the Israeli left (Labor + Meretz) Yair Golan, who last week walked back his poorly-articulated criticism that his compatriots were killing babies in Gaza “as a hobby.”

The words were wrong, but Golan’s critics hoped to capitalize on this gotcha moment to change the subject from the unpopular, unnecessary, unplanned and brutal reconquest of Gaza, and intimidate others from speaking out.

Ehud Olmert, who has been defending Israel from day one, as so many of us have, did not get the memo. Imagine if George W. Bush were to pen an op-ed calling out Trump. At this point, it would take Bush, Mike Pence and at least two current GOP Congressional leaders to break through. But courage does tend to be contagious.

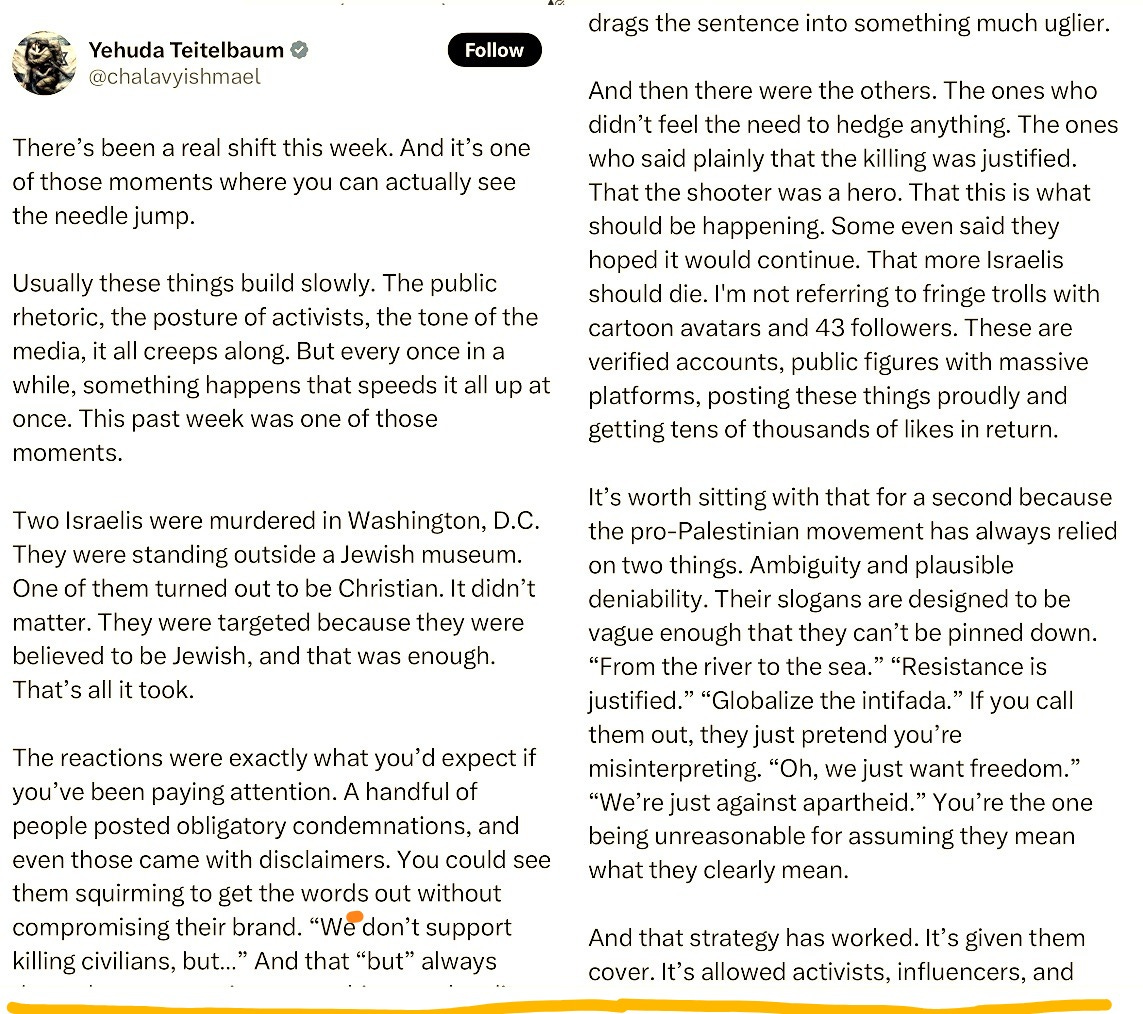

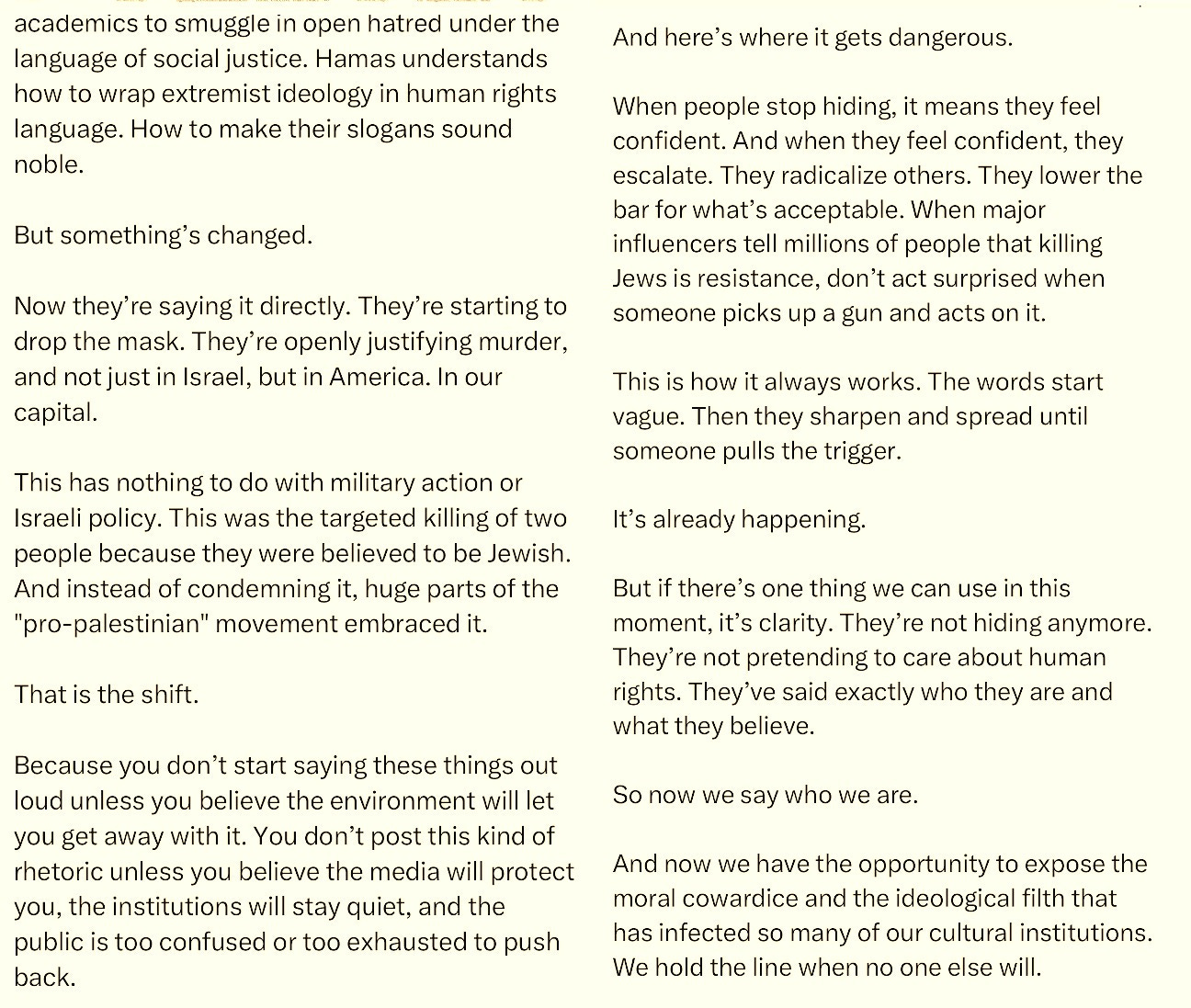

Yaron and Sarah’s Murders

Israelis’ eyes might be opening to suffering in Gaza; but this was also the week when many became conclusively aware of the innate and dangerous antisemitism of the most virulent strains of the “Free Gaza” movement here in America, which was exposed for all to see in the DC murders.5

See Ken Klipperstein’s analysis (link below) of the murderer’s leaked posts, which to Ken, indicate that he was motivated by a hatred of Israel, not antisemitism. I see it as a distinction without a difference. Unless he was targeting those two specific people, who worked in the embassy (one of whom was not Jewish), he was aiming for Jews, and not specifically Israelis. Or he conflated all Jews with Israel supporters. Having watched her heartbreaking funeral yesterday6, no one could represent the absolute best of American Jewry as much as Sarah Milgrim. Her rabbi, Doug Alpert, another Rabbi Fisher award nominee, said of her in his moving eulogy:

Sarah stood with and stood for many marginalized groups yes for Palestinians because she spent the time to get to know individual Palestinians and could see in these individuals their humanity and all that she and they had in common. She stood for the rights of the LGBTQ+ community - The trip she was to have made right now was to have been to Israel which included taking a group to participate in the gay pride parade. And yes, Sarah stood for us, for Jews everywhere.

Close friends Sarah had made in her graduate work ostracized her when she began working at the Israeli embassy. What a horrible disservice to not see her for who she was and all she had done to further peace with courage and dignity. Because if you really wanted to know how to give Palestinians a better life, a life of humanity and dignity, you could have asked Sarah. And it was Sarah who courageously forged relationships with Palestinians and with Muslims - and I commend to you an essay in the NYT by Sarah's Moroccan Muslim friend. If you're really interested in doing something for Gaza to end the blockade and get needed aid into Gaza you could have asked Sarah. After all it was the reason Sarah and Yaron were attending an event at the capital Jewish Museum last Wednesday night - to end the blockade and to get needed aid into Gaza.

And if you were really interested in creating solutions to this seemingly endless conflict that separates Jews and Muslims, Israelis and Palestinians you could have asked Sarah. Sarah's commitment to a “Third Narrative,” a concept in which instead of violence and vengeance was focused on shared humanity and the mutual right to dignity.

And if you really cared, if you're about more than cancelling voices that made you uncomfortable about more than shouting slogans and waving a gun then damn it why didn't you ask Sarah? I'd like nothing more right now than to ask Sarah to talk to Sarah to learn from such a beacon of light amidst a world of darkness. We've been cheated out of that opportunity.

Either way, as a whistleblower revealing this important information about the killer, texts that may or may not conform to people’s preconceived narratives, Ken earned a visit from Trump’s FBI - and for that he is another profile in courage. He gets an additional Rabbi Mitchell Salem Fisher award for this week.

Freedom of Speech Under Attack

Meanwhile, back here in our American dystopia, we normalize daily abominations coming from the White House. Scott Pelley of 60 Minutes called out his own bosses and rose to the rhetorical occasion in an address to the graduating class at Wake Forest last weekend. He said (about 25 minutes in on the video below):

In this moment, our sacred rule of law is under attack. Journalism is under attack. Universities are under attack. Freedom of speech is under attack…. Why attack universities? Why attack journalism? Because ignorance works for power? … Today, great universities are threatened with ruin… First, make the truth seekers live in fear (of retribution, censorship or deportation). Sue the journalists and their companies for nothing. Then send masked agents to abduct a student…then send her to a prison in Louisiana, charged with nothing. Then move to destroy the law firms that stand up for the rights of others. With that done, power can rewrite history, with grotesque, false narratives. Power can change the definition of the words we use to describe reality. This is an old playbook, my friends.

Pelley’s courageous remarks, deserving of another Mitchell Salem Fisher prize, reminded me of the one of the seminal moments in the history of television - which came in form of a “rabbi’s” sermon. Comedian David Steinberg’s rabbinic sermon on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour back in 1969 presents a sad contrast to the cowardice that is so prevalent now on legacy media. This “sermon” was deemed so offensive that it got the show cancelled. 7

Lots of winners this week. A thousand points of light in the midst of these dark times. But we need more.

The rabbi, priest, imam or minister who is not crying out right now, who, as Rabbi Fisher said in 1930, is content to “enunciate ideals, but these must remain so indefinite, so unpointed, so unchallenging, so completely removed from the real issues of everyday living and struggling, that these ideals become patently and utterly vain” - that person is failing to do the job that is needed in this moment.

That job is to express outrage as accurately, firmly and creatively as possible, in a manner that motivates the conscience and generates action.

What’s true for religion is true for the press as well. The journalist who is still aiming for “balanced coverage” right now is no journalist.8 These times demand better. We must all answer to a higher authority.

And that higher authority is truth.

Here is another example of courage on the pulpit. A subscriber to this Substack, commenting on a recent piece, mentioned how his great, great grandfather was an excommunicated Catholic priest in France. At my request, he filled in some of the details of an amazing profile of courage and love:

His name was Pére Hyacinthe Loyson. He was the head of the Paris Carmelite Convent and gave sermons at Notre Dame as well as across Europe and America. He answered directly to the Pope. He was assigned to counsel an American widow who wanted to convert to Catholicism. They became close friends (and I believe fell in love) and at the ecumenical council of 1869, he questioned the decision to declare the Pope infallible, saying it was heresy and only Jesus was infallible. He was immediately excommunicated and escaped on a ship to America, where he was warmly received. His American friend who stayed in France arranged a house in Geneva for him to return to, since if he had returned to France, he would have been jailed and probably executed! She met him there and they married and had a son about a year later, Paul Hyacinthe Loyson, who also became a celebrity in France. After the Pope died in 1872, the next Pope was no other than Pope Leo XIII. Yes, the pope who inspired our new Pope. Pope Leo XIII was kind and allowed Pére Hyacinthe to move back to Paris and start his church based on the German Catholic Church, which allows priests to marry. The church still exists today. His sermons were mostly about the rights of the family and the right of all men to have a family. His sermons at Notre Dame were extremely popular, with standing room only, attended by statesmen and the upper class as well as the general public.

Pére Hyacinthe Loyson understood the meaning of “Good Trouble” and he was willing to risk excommunication for it. This is precisely the kind of courage and risk-taking we need right now in public life.

See also Thomas Friedman: The Flashing Signals That I Just Saw in Israel (NYT)

“It is premature to call it a broad-based antiwar movement, which can happen only when all the Israeli hostages are returned. But I did see signals flashing that more Israelis, from the left to the center and to even parts of the right, are concluding that continuing this war is a disaster for Israel: morally, diplomatically or strategically.”

Sarah Milgrim’s funeral. The rabbi’s eulogy encapsulated just how remarkable she was - and how tragic this is.

In truth, while the program often protested US policy, particularly the Vietnam War, this sermon was just a little cute poke at Christianity for having a history of antisemitism. The bit would be considered tame today, but in Trump’s world might still have been censored on network TV, only to appear two weeks later on Netflix.

As they say in Hebrew, “Hamayvin yavin,” “Those who understand will understand.”

Speaking of balls, Netanyahu dropped the ball by ignoring Hamas and just trying to buy them off, bad, bad mistake. Yes, their both leaders let them down, Israel and Palestine. Peace in Israel has always been fraught with conflict. Way before this creep Netanyahu. Now Gaza and the poor people left their are in tatters. And the U.S. leadership has plenty of blood on our hands. This is what I want to know! Why can’t we ALL just get along? Why are humans wired for conflict all the time? When will we ever find PEACE?

I wish I could respond with words as stirring and unsettling as yours, but instead I am convicted and without words…..only thank you!