This Passover, kosher pig’s on the menu

Modern Jewish life is filled with kosher pigs, utter inconsistencies we sometimes hardly notice; but they are there, and they are enlightening.

(RNS) — This year, Passover begins on a Saturday night, something we haven’t experienced since 2008. According to Rabbi David Golinkin, this anomaly occurs only 12% of the time.

And whenever it occurs, people invariably ask two questions: When should we stop eating hametz (prohibited leavened products)? And the corollary, by when should our house be completely clean for the holiday? On Friday morning or Saturday morning?

The standard response is the house should be ready on Friday, before Shabbat, instead of the morning of the Seder (this year Saturday), which is usually the case. For most Jews, who are secular in most respects, the premise is based on an utter inconsistency. Many will have their houses ready for Passover by Friday afternoon because they want to do Passover “right,” when in fact they’ll be rushing their preparations in order to keep Shabbat rules they don’t normally keep.

To be “consistent” with their normal practice, the non-Shabbat observer should consume leavened products until Saturday — not Friday — morning. Why should this Shabbat be different from all others?

The late Rabbi Richard Israel once wrote a book titled “The Kosher Pig.” The intriguing title stems from a story he tells about a pious Jew who was told by his doctor he had a rare disease that could be cured only by eating pork. Now, Jewish law states that in order to save a life, virtually any of the law’s requirements can — in fact must — be broken. But that wasn’t enough for this man. He determined the pig had to be slaughtered in the kosher way, painlessly, before he ate it. So he brought the pig to the local ritual slaughterer, who acquired a special knife that would never be used on a kosher animal. After slaughtering it in the “proper” ritual manner, the shochet examined the pig’s lungs to look for blemishes. He had no idea what he was looking at, but he finally concluded the lungs had no serious abrasions (and was therefore “smooth” or “glatt”).

“So, nu?” the man asked, “Rabbi, is this pig kosher?” The rabbi examined the lungs for some time and then declared, “It may be kosher, but it’s still a pig.”

Modern Jewish life is filled with kosher pigs, utter inconsistencies we sometimes hardly notice; but they are there, and they are enlightening.

Which brings me back to Passover. The same thing happens every year regarding dietary restrictions. On Passover, many Jews who otherwise do not keep the dietary laws in their everyday lives become fanatic about ridding their homes of leaven and bringing matzo sandwiches to the classroom or office. A ham-on-matzo sandwich is hardly an unthinkable scenario in this perplexing world of kosher pigs. It’s kind of like the guy who drives to synagogue on Yom Kippur but tells the policeman writing him a ticket he can’t put money in the meter on a Jewish holiday.

Some more gems from Israel’s book: “An observant Jew has just made a serious pass at me. Do you think he will want me to go to mikva (ritual bath) before I have an affair with him?”

And another: One commercial fisherman in California called his rabbi to see if it was kosher to use pieces of squid as bait when he goes fishing. An interesting question, because squid has no fins and scales and is therefore unkosher; but does it affect the Kashrut of the fish caught? A fascinating question, except he called the rabbi on Saturday morning to ask it.

Oy.

All of these people are, to some degree, serious Jews, and for that alone we must commend them. We might laugh at the inconsistency, we might even call it hypocrisy, but if they are hypocrites, we should all be so hypocritical. We all must learn the difference between pretending and striving, between going halfway in earnest and throwing it all away without giving it half a chance.

To be a hypocrite means at least we’ve set high, virtuous goals for ourselves, even if we don’t always live up to them. I’d rather do that, and fall short, than set no high standards at all. Most of us are so afraid of being called hypocrites we take the easy road. If we expect little of ourselves, we usually deliver.

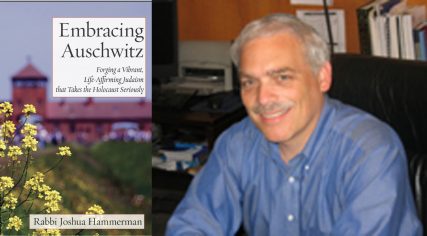

Right, Rabbi Joshua Hammerman and his book “Embracing Auschwitz.” Left image courtesy of joshuahammerman.com; right image courtesy of Temple Beth El

So as we approach this unusual alignment of Passover and Shabbat, let’s allow for a little kosher pigheadedness. For those Jews and others who’ve rarely kept Shabbat in this manner before, don’t feel funny about keeping it a little more meticulously this time. It’s OK to be inconsistent.

You might even enjoy it.

https://religionnews.com/2021/03/25/this-passover-kosher-pigs-on-the-menu/

(Rabbi Joshua Hammerman is the spiritual leader of Temple Beth El in Stamford, Connecticut, and the author, most recently, of “Embracing Auschwitz: Forging a Vibrant, Life-Affirming Judaism that Takes the Holocaust Seriously.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

No comments:

Post a Comment