2023 Rosh Hashanah Sermons

Click for Audio Only of Day 1 Sermon

Click for Audio Only of Day 2 Sermon

Click for Video of Day 1 Sermon

Click for Video of Day 2 Sermon

A Matter of Time

Rosh Hashanah Day 1, 2023

Rabbi Joshua Hammerman

I’m going to begin with a quote from the New Testament – a little unorthodox, but no one has ever accused me of being orthodox. A wise teacher once said that there are four words you can say on any occasion: “This too shall pass.” His student asked him, “Really, any occasion?”

“Yes.”

“So would you go up to a bride at a wedding reception and say to her, “This too shall pass?”

And the teacher said, “Absolutely. It’s precisely the couples who understand that the exhilaration of their wedding day will soon pass who go on to have the most successful marriages.”

Since I arrived at Temple Beth El in 1987, I’ve delivered a total of 134 High Holiday sermons. Four to go. Our honeymoon ended decades ago; but an incredible marriage has endured. And at no moment did I fail to realize that someday, this too would pass. That day has arrived.

Thirty-six years ago, double chai, my journey and yours came together. It seems like forever – and it has been a long time. To give you an idea of how long, one month after my opening night here, Les Miz opened on Broadway. That run, when it closed, was the second longest in Broadway history. It closed twenty years ago, on May 18, 2003.

I came here just as President Reagan was in Berlin, saying, “Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” Now you can buy a piece of the wall on ebay. Barbie was quite the rage, but it was Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyon, who was convicted for his war crimes. The doll has had some recent legal problems, but genocide is not among them. The worst thing she ever did was wear white after Labor Day. The Golden Girls (NBC) won the Emmy for Comedy. The actresses who starred were all much younger than their ages on the show – but they’re all dead now - though Betty White, God bless her, had quite a run.

It was a long time ago.

My pension director tells me that maybe only a dozen Conservative rabbis in this country have remained with their congregations for this length of time. It’s a tiny pool – too small for any survey to accurately measure – and the pool is shrinking. It just doesn’t happen anymore. Once upon a time, such stability was the norm – the gold standard for a congregation. Now, research has shown that most pastors vacate a pulpit between the years 3 and 5, if they last that long. But somehow, we bucked those odds. It wasn’t easy. But it is easy to take that remarkable accomplishment for granted. I certainly don’t. I am totally aware that this is not just any old goodbye, and for many of you, it’s as hard for you as it is for me – and for some maybe even harder.

So, we are a unicorn. I say “we” because this is as much your accomplishment as mine. In this congregation’s 102-year history, there have been essentially just three senior rabbis, with a few short-term flame-outs mixed in.

I understand that for each of you, this transition is something different. I’ve known some of you for thirty years, others for two weeks. But they’ve been two good weeks! And now, each of those clocks is synchronized, as we count down inexorably toward zero.

And as lengthy as this journey that has been, it has also passed like the blink of an eye. “How long is forever?” asked Alice. To which the White Rabbit replied, “Sometimes, just one second.”

Sometimes forever feels like just one second.

We’ve been blessed with long term clergy, but a 37-year run has never happened here before. That leaves us as among the only ones sharing the priceless opportunity to have prayed, cried and laughed together since before Jean Valjean first stole that loaf of bread at The Broadway Theater.

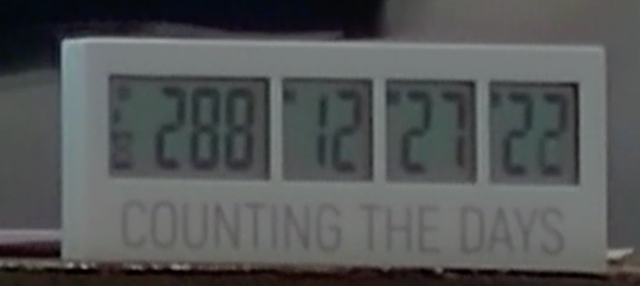

But no time to dwell on nostalgia. Time’s a-fleeting. We only have One Day More. Actually, according to my official handy-dandy CNN countdown clock, we have exactly

left until next June 30 at midnight. So, no time to waste.

So today, let’s talk about time – what it means for us all to be stewards of the clock and how we can learn to look at time in different and less gut-wrenching ways.

I grew up in Brookline, Mass. and loved my childhood. Brookline was my little shtetl. I loved it all, and wanted things to stay exactly as they were. When I was a kid, I learned how the biblical Joshua made time stand still and I wanted to do the same.

For my bar mitzvah, I got my first digital clock. It was one of those rudimentary “Flip Clocks” – no LED screen – each minute flipped over with a discernible click. As I lay in bed, I was keenly aware of the passage of time, but I had no idea how brief my childhood would be.

My youth was shattered forever at age 21 when my father’s heart stopped. Just two days earlier, my parents had closed on the sale of my childhood home; and two months later, my mother moved out and that was that. I still carry the key to that home.

Exiled from Anatevka and my childhood innocence, and since I could no longer stop time, I was now determined to outrace it. Always keeping my foot on the gas.

I graduated from Brown in three years to save my parents a few bucks. I rushed into rabbinical school without hesitation, which was my dad’s dream for me and a little bit mine too. Gap years were not an option for me back then. And then my father died suddenly while I was in my first year at JTS, and despite some misgivings, I stayed.

While I studied at the Seminary by day, I took the Broadway local down to NYU to earn a journalism degree by night. Two full-time graduate programs simultaneously. By age 26, with a rabbinic ordination in one hand and a masters in journalism in the other, I looked for ways to combine the two careers. I interned at the Daily News. I freelanced articles at major publications and soloed at pulpits in Beacon and Peekskill. And at age 30, you hired me.

Five years later, I became the senior rabbi, very young for a place like this. But I was more than ready – always in a hurry - I never stopped running, running against the clock.

And then the years passed. We added one kid, then another. We added a dog. Then another, and another, and another. And another. I partnered with a parade of all-star cantors, great educators, administrators, staff and lay leaders. All the while I never stopped to smell the roses. No break. No Sabbatical. Few real days off. Nonstop.

I feel like I’ve been living a line from Hamilton.

Why do you write like you're running out of time?

Write day and night like you're running out of time?

Every day you fight, like you're running out of time?

Or maybe my life is more like a Purim song.

Hava narisha, rush, rush rush!

Yes, I can’t believe how quickly our time together has passed. I can’t believe how quickly my life has flashed. My stepping off this hamster wheel next July may not make the wheel go much slower, but it certainly couldn’t go any faster.

But… this sermon is not really about me. (That’s next week.) So let me talk about you. Us, really. Us and time.

We are a generation obsessed by the clock. We can’t stand still. We can’t slow down. We live in a permanent state of shpilkes. I know that whenever I run into traffic on the Merritt Parkway, which is anytime I’m on it except for 3 AM, I feel claustrophobic. We need to be moving forward, or at least to create the illusion of moving forward.

Robert Pirsig wrote in his novel, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, “We’re in such a hurry most of the time, we never get much chance to talk. The result is a kind of endless day-to-day shallowness, a monotony that leaves a person wondering years later where all the time went, and sorry it’s all gone.”

And it’s on all of us. We are overpowered by the need for productivity. We are on, 24/7. That’s the way it’s always been for clergy. But now everyone’s a rabbi. Welcome to my world! No one has real vacations anymore. And we think that by the sheer intensity of our activity - if we accomplish more things -that somehow we will make things better. But things aren’t better, and we’ve lost our way! We’ve lost track of time and our lives have been derailed.

Does anybody really know what time it is

Does anybody really care? About time?

If so, I can't imagine why

We've all got time enough to cry….

Our culture, our music, everything – there is an obsession with time.

But there are two things that could never be dominated by a clock. Two things! Shabbat… and baseball.

Ah yes, baseball. No one had the patience to watch it anymore, so this year they brought in the pitch clock. And people love it, which is terribly depressing. And I love it, which is even more depressing. We’ve lost all patience.

Incidentally, I’m thinking of bringing the idea into our services. No, not for sermons. Puh-leeze! For aliyahs! When the Cohen comes up to the Torah, I start the clock. You gotta get into the batter’s box and kiss that Torah. If you don’t finish the blessing in 20 seconds, a shofar will sound, the next person will be called up, and for you, better luck next year.

How about Hamotzi! If you don’t eat the challah within 10 seconds of saying the blessing, you’re out of luck. We’ll give you a piece of kichel instead – the only cookie ever sent back by the Sahara Desert for being too dry.

We actually are on the clock for lots of Jewish rituals. When you escape danger or complete a long journey, there is a prayer called the Gomel blessing. It has to be recited within three days.

There’s also a prayer said after going to the bathroom when we wake up, called Asher Yatzar. It’s a lovely idea, to appreciate the sacred complexity of our bodies. But you gotta say the prayer within a half hour after you’ve gone. Why a half hour? I have no idea. Some say it’s because you may have to go again. For Sefardim, by the way, it’s 72 minutes. Draw your own conclusions. I can imagine the Talmudic discussion: “Buuuut if you have no Lysol, you can wait an hour and a half!”

But the point is, the clock is always running, even for blessings. We’re always on the clock.

And don’t I know it!

OK, we can all agree that baseball needed to get faster. But in general, why do we have less and less tolerance for things that take longer? Like services in Conservative shuls. So, we’re supposed to throw out prayers that have been recited for two thousand years? The answer: Yes. It didn’t bother my great grandparents. But it seems like our brains are moving faster now. We need to speed things up, just like television commercials need to speed up, just like traffic needs to go faster, just like meals need to go faster so we zap ‘em, just like information needs to flow faster, so we play videos and podcasts at one and a half speed, and everyone sounds like a chipmunk. Everything goes faster…just like vacations need to go faster, just like careers need to go faster. Just like life needs to go faster.

Everyone is on a fast track to nowhere.

But here’s a paradox. We are so sidetracked by all the multitasking, we’re so busy being busy, that we’ve lost control of time and we neglect to do those things that have to be done. As life whizzes by faster, we increasingly procrastinate, and put off that phone call to a sick relative; the “I love you” to a partner or child; that letter to an elected official; that volunteer project. There is always something else to do. And just as we’re about to do it, a banner pops up on the screen, interrupting our train of thought.

I’m a notorious procrastinator. I wrote this sermon yesterday. Well, not really, but where Hillel said, “If not now, when?” my motto is, “If not now, later!”

Why are we in such a hurry? The more we rush, the more time outruns us. A day. A month. A year. 525,600 minutes – and time keeps on slipping, slipping – beyond our grasp.

We need to look at time differently.

And here’s how:

This gift from an artist at my prior congregation has been hanging in my office here since the day I moved in. I reflect on it every day. It’s a verse from Psalm 90.

“Teach us how to count our days, that we may obtain a heart of wisdom.”

Note that the translation is not “Teach us to count our days.” We already do that! But rather, teach us HOW to count them. Teach us new strategies so that we may escape the tyranny of time. Teach us how to count our days, rightly.

So, this morning I’m going to share a few ways to do just that. Here’s how we can count our days - differently.

Psalm 90 is perhaps the wisest of Psalms, and the only one ascribed to Moses. It states:

The span of our life is seventy years,

or, given the strength, eighty years;

but the best of them are trouble and sorrow.

They pass by speedily, and we are in darkness.

Life passes us by in a flash, it is saying – but only when we live in darkness. When we sleepwalk through life, we become prisoners of the clock. The Psalm is saying that we can’t allow ourselves to put our one wild and precious life on autopilot. Message one: Wake up! Live mindfully.

Message two: Look at time through Heaven’s eyes.

Psalm 90 asserts:

כִּ֤י אֶ֪לֶף שָׁנִ֡ים בְּֽעֵינֶ֗יךָ כְּי֣וֹם אֶ֭תְמוֹל כִּ֣י יַֽעֲבֹ֑ר וְאַשְׁמוּרָ֥ה בַלָּֽיְלָה׃

For in Your sight a thousand years

are like yesterday that has passed,

like a watch of the night.

In our sources, a “watch in the night” is considered the shortest span of time measurable, equivalent to what we would call an “instant.”

In other words, the length of our life’s journey is unbelievably brief in comparison to eternity, whether we live 120 years, or 120 seconds. A thousand years is nothing, from a God’s eye view.

It’s humbling – for sure – but in a strange way, hopeful, to look at time as God would.

So, let’s do that. Let’s zoom out and see what God sees, the very, very big picture.

What’s it like to flash forward a thousand years, or 10,000?

The rabbis brilliantly managed to make the square peg of our lunar calendar fit into the round hole of the seasons, by adding an extra month seven times in a nineteen-year cycle. In this way, Passover would always fall in the spring in the northern hemisphere and Rosh Hashanah in the early fall.

But here’s where it gets fun: their calculations were just a little off. The Jewish calendar is shifting ever so slowly. As a result, the first day of Pesach is getting later by one day every 231 years on the Gregorian calendar. Eventually, Passover will fall in the summer.

And using these calculations and planning way ahead - ‘cause if you’re God, you can never plan too far ahead - in the secular year 22,203, which corresponds to the Jewish year 25,963, for the first time, Rosh Hashana will fall on January 1. And we’ll get two New Years for the price of one! …Which will be very convenient for anyone who might celebrate a little too much the night before and need to repent the next day. I can just see the big apple in Times Square being dropped into a big vat of honey! It will be spectacular.

If this God’s eye view is making you a little dizzy, let’s reel it in a bit – to the Gregorian year 6242, which is the Jewish year 10,000, just 4,219 years from now. That is the first time Yom Kippur will coincide with Halloween. We’ll be able to go straight from Break the Fast to Trick or Treat. Or maybe combine them. Everyone will gather at that haunted house down the block and instead of M & M’s they’ll they give out pickled herring.

Looking at time from a God’s eye view forces us to ask some difficult questions:

- Will there even be an America 4,000 years from now?

- Will the High Holidays be celebrated on Mars that year? We have no idea whether there will be an inhabitable Earth in 40 years, much less 4,000.

Which is why this exercise calls on us to be like the Iroquois nation, looking at the impact of every decision we make today on the 7th generation.

But we do know one thing. We all know that in 4,000 years, Eileen Rosner will still be dressing the Torahs. And we know exactly when Rosh Hashanah will begin in the year 6242. It will begin…when the sun sets. Jewish time will still be governed by the rhythms of nature. When you look up in the sky – and not at your phone - you’ll know what time it is. And you’ll care. About time.

Just as we know that today is Shabbat because we aren’t blowing shofar, because God rested and allowed the world to breathe for one day. And we slow down and breathe too – and that’s what happens when we take a God’s eye view.

Before we relinquish our God’s eye view, I need to add one more thing. True, none of us will be here at Temple Beth El in 6242 – hey, I won’t be here in 2024. But whether or not this synagogue is standing, something, something inside me – some gut feeling tells me that there will be a Torah. There will be a Judaism and a Jewish people. In 4,000 years, there will still be Jews, just as the Jewish idea and Jewish people came to this world around 4,000 years ago.

How could our people not persist through the millennia? We’ve just survived genocide. If we can survive that, we can survive anything. If we can survive the Romans, Inquisition, Cossacks, Czars and Nazis, we can survive synagogue shootings, or secularization, or the Protocols of Zion, or BDS or the judicial coup. We’ll even survive Elon Musk! (Which is more than I can say for Twitter).

From a God’s eye view, the Jewish people will be here in thousands of years because we’ve already proven that we can last thousands of years.

For a hundred generations our ancestors prayed to return to Jerusalem three times daily. A hundred generations. If just one generation had stopped facing Jerusalem, we wouldn’t be here. Each person mattered. Each prayer recited by each person – it mattered. I wouldn’t bet against the Jewish people, despite the great challenges we face now, here and in Israel. I wouldn’t bet against us, and not because of God (which I can say from this God’s eye view) but because of each of you. Each of you matters. And I know you’ll come through. Why?

Because you are here today!

Something mysterious has drawn you back here today.

And that’s why our little speck of time along this journey, this journey that we’ve taken together – matters. These 36 years we’ve been together – they’ve mattered. And that’s why your life matters, and my life, they’ve all had a purpose, and all those who are buried next door at Beth El Cemetery, their lives did too.

Teach us to count our days. Teach us how to count them. To look at time from God’s perspective and see the big picture. The huge picture. For that’s the key, not just to our relevance, but to our immortality, which rests on the indestructibility of the Jewish people and the Jewish idea.

We say in the concluding Torah blessing: Asher Natan Lanu Torat Emet, V’hayey Olam Nata Betochaynu – Who has given us the Torah of Truth; and eternal life has been implanted within us.

The truth of Torah transcends time. And so will we.

So, Psalm 90 teaches us to look at life through heaven’s eyes.

Frankly, this would be a great place to end this sermon. It’s a high note. But I’m not done yet. I’ve got (look at clock) miles to go before I sleep.

For there are other ways to recalibrate our concept of time. So put your brisket on a timer and stop looking at your watch!

One thing we can do is move to France. In France I could have retired five years ago! But why retire at all when everyone spends half the day in a café anyway. In fact, in France – and, this is true because I read it on the internet - arriving on time to a dinner party is considered rude. The proper etiquette is to arrive around 15 minutes late. Their sense of time is so totally different from ours. Teach us, O God, to count our days – en Francais!

But you don’t need to be in Paris to sit at a café. The bestselling poet and essayist Ross Gay decided to slow time down by stopping to reflect on one special delight for each day, for a year. His Book of Delights is delightful, and a perfect Shabbat read.

In one of his daily reflections, he sees a sign while he is sitting in a café in Detroit. It says, “No Loitering.” Well, he asks, what exactly is it, that you’re supposed to do in a café? Ross Gay notes that loitering “implies being unproductive...and that is a crime in America.” He adds that it is particularly menacing if you are, like him, Black, and especially if you are wearing a hoodie. But, whatever our ethnic background, we need to learn how to let go of the reins and, rather than chasing the clock, set-a-spell, and let time come to us.

So, Message Three of Psalm 90: Teach us to count our days - and loiter. Or better yet, meander. What a word! Just saying meander requires that we meander. Sitting in a garden and sipping an iced tea. Or better yet, a Fribble. You can’t drink it too fast. Brain freeze.

In her new book, Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock, Jenny Odell lays out the case for us to recalibrate how we look at time. As Odell puts it:

Maybe "the point" isn't to live more, in the literal sense of a longer or more productive life, but rather, to be more alive in any given moment, a movement outward and across, rather than shooting forward on a narrow, lonely track.

Living outwardly – that’s Message Four – and it means embracing each moment as an opportunity to reinvent ourselves, to change our history and redirect our future. The idea of finding ultimate meaning in every little action - and the infinite possibilities resulting from our every choice, like this year’s Oscar winning film, Everything, Everywhere All at Once.

Living outwardly also means looking at time not from a God’s eye view, but with our ear to the ground, listening to the rhythms of the tree in the forest. For a tree, a century is a day.

And what about geological formations, where mountains are still in their adolescence; or coral reefs gasping for breath like end stage emphysema patients. Or the rhythms of gardens growing, birds migrating, beaches eroding, species disappearing, all on different but interlocking timetables.

(See links that access a live webcam of the Great Barrier Reef bleaching and daily images of Greenland’s ice sheet melting.)

Each sunrise has its own special rhythm. There is a sunrise every day, but the lovely sunset that happened this morning, the one that ushered in this new year, that one will never occur again. Odell comments, “Each one gives us an imagine of renewal, return, creation and a new day.” That’s how I want to measure time. And in fact, we do – our morning prayers reflect those exact sentiments.

And each tide. Tides shift by about a half hour every day. As I stand by the shore, I can almost feel the tug o’ war between the earth and the moon, shifting ever so much as the waters come in and go out.

We’ve just purchased a house in Madison CT where we’ll be moving; fifty miles away, not too far but on the Red Sox side of the state, safely across what I call the "DiMaggio Line." It’s right near the beach, and already, I am reconnecting with those eternal rhythms that call me back – as they did when I spent childhood summers on Cape Cod. I’m already beginning to slow down and synchronize my inner clock to the rhythms of those undulating crescendos of water, surf and sand, and to look out over the deep blue swells and see, out in the distance – Long Island. OK, nothing is perfect.

And right here, we are so, so fortunate to witness this seasonal dance outside our window and to set our clocks to it. Every week it’s different. Every week, we connect to these eternal rhythms of nature. You can sit in this sanctuary once a week and it will completely alter your sense of time – simultaneously binding you to the rhythms of nature and Jewish history.

When the beautiful Matthew Klein Garden was put in a few years ago, I was sure it would forever bury another, more modest garden planted on the same spot, by our seventh-grade class in 2007. The kids took great pride in it, but it was nothing elaborate – maybe a hundred randomly planted daffodils in memory of victims of the Holocaust, timed to bloom just before Yom Hashoah.

The daffodil symbolizes rebirth, and its appearance signifies the end of the cold, dark days of winter. In some places it is called “February Gold.” In Israel, one form of it, known as the Sea Daffodil, blooms later in the year, in the harshest heat, when nothing else will grow. In the Bible’s Song of Songs, it is nicknamed Havazelet Hasharon, mistranslated as a “rose” of Sharon. A moshav by that name is located just north of Netanya. Gorgeous spot.

These intrepid flowers are always racing to push themselves out of the ground when it’s too cold or too hot for anything else to budge, proclaiming every year, we are still here! The daffodil is bold – and a little full of itself, which is fitting, being from the narcissus family. But in its willingness to be the first to stand up and be counted, to say to the rest of the flowers, like an IDF officer, “Follow me!” - what better way to both declare the end of the dark winter and bring light to the darkness brought about by the Shoah than to see these biblical flowers in bloom, right outside our windows.

And so, the year after the Klein Garden was planted, I paced nervously like a parent waiting for a child to come home from a first date. And sure enough, in mid-March, the first daffodils poked through the ground.

They were still there.

And every year, right on time, between Purim and Passover, we get a splash of yellow and white, and every year, I celebrate the return of Havazelet to our grounds. A little bit of Israel’s coastal plain, close to where Hannah Senesh sang about the sand and the sea, and right out of the Song of Songs, right in our backyard.

We’re growing the Bible in our garden.

And then, every year, just a few weeks later, the Klein Garden suddenly awakens from its slumber, and its flowers burst into bloom and surround the now withering daffodils, as if to escort them back into the earth, thanking them for their service. Like our heroic Shoah survivors whom we are now chaperoning through the final years of their lives. This Holocaust Memorial Garden annually proclaims the unbreakable connection of our children to the eternal cycles of nature AND Jewish time - and the memory of the Six Million. I set my springtime watch by those daffodils.

And now, I leave the Havatzelet in your care. Watch for them every March and think of our seventh graders from 2007.

Here’s another way we can look at time.

In her book, Jenny Odell brings up a form of time well known among the disability community, what they call “crip time.” Crip time enables us to live time at a slower pace.

Many of you know that my brother Mark in Boston is significantly challenged, with Fragile X Syndrome. Over the past couple of years, to add to his many health issues, walking has become increasingly difficult for him. He shuffles very slowly, measuring each step before moving one foot, then the other. If he ever were relegated to a wheelchair, it would be game over.

Once this summer when I was up there for a visit, it was raining really hard when we arrived at the parking lot at Panera. He was terrified – I’d never seen him struggle so much. We both got soaked as he grasped my arm tightly. I had no idea how difficult walking had become for him, just in the few weeks since my prior visit. It took fifteen minutes to get from my car a short distance to the front door. And for those fifteen minutes, that became the focal point of our lives – fifteen minutes that seemed like hours. I marked time on Mark’s time. And I understood what it is like to live on “crip time.”

Odell writes: Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds.

She adds that disability highlights something that is true for all of us: no matter how independent and fit we may feel, we are not simply alive, but, rather, kept alive: People do not spring up from the soil like mushrooms; people need to be cared for and nurtured throughout their lives by other people…. aliveness means touching and being touched.”

We are all on different clocks. We walk at different speeds. We learn at different paces. We pray in different rhythms. But in the end, we can’t mark time alone. All our clocks chime differently, but our goal should be to make them chime in harmony.

Teach us to count our days – to measure those paces, so that our hearts may be guided by kindness, as we hold out our hand to help our siblings shuffling with a numbing fear through the rain-soaked lot at Panera.

Around the beginning of 2020, I was diagnosed with a significant health challenge, which has completely altered the way I measure time. It made me more intentional in dealing with the Covid threat and has guided my planning for a life beyond the pulpit.

But even more, it made me incredibly appreciative, beyond words, to those who have shown kindness to my family and me over the years. The kind words so many of you have offered since I made my emeritus announcement, sharing the memories of our special times together. We’ll have more opportunities to do that. I’ve learned how to count my days – and my blessings.

And as I held my brother’s hand, drenched in that parking lot, and saw how dependent he was on me and in a strange way vice versa, I realized that however we mark time, our time is meant to be shared.

I visited Mark again last week and took him to dinner at Coolidge Corner. I’m happy to say that it went much better. He’s doing better. He’s still walking.

Today is Shabbat. The very fact that Shabbat supersedes Rosh Hashanah, and we don’t blow the shofar today, is a key sign that, from the Jewish perspective, the relentless march of time needs to pause and take a back seat to this weekly taste of eternity. It’s a lesson we need to learn, even if it means delaying our shofar gratification for one day. And we need to sit back and cherish our remaining time together.

Rosh Hashanah is all about our rush to get things done. Shabbat is about the appreciation of what we’ve done already. Rosh Hashanah is the forced rush of a Tekia Gedola, creating waves of sound. Shabbat is a light breeze that ripples across the surface of the water.

Hayom Harat Olam – Today the world is born, but we’ll hold our breath one more day before celebrating that birthday tomorrow, with the shofar’s blast.

Once a busy merchant went to the rebbe of Lekhowitz and asked how he might attain humility. While he spoke, the clock struck the hour. The rebbe said, “This is your answer. Nothing should humble us more than the striking of a clock. We know that another hour of our lives has passed, and we should think: What have I done in this hour and how have I improved my soul through the service of God?”

The clock humbles us for sure. But it also liberates us to take control of each day, each moment, and live our lives to the fullest – something that can best be done on Shabbat.

And so, I call on all of us to set our lives to the rhythms of nature, to the undulations of Jewish time, of memory and beauty. Meander through your days. Live intentionally. Find your place in the vastness of eternity. Set your watches to the pace of the one who is struggling to keep up and always extend your hand. Seek the path of hope, bolstered by the belief that our lives do matter. Be grateful for every moment we’ve shared together. Our time together has mattered. And if we don’t know it now, it will be known in 4,000 years.

And, next March, as we watch our daffodils herald yet another new spring in honor of our precious students and in memory of our martyrs, we shall harken to the opening verse of Isaiah 35:

יְשֻׂשׂ֥וּם מִדְבָּ֖ר וְצִיָּ֑ה וְתָגֵ֧ל עֲרָבָ֛ה וְתִפְרַ֖ח כַּחֲבַצָּֽלֶת

The desert and the parched land will be glad; the wilderness will rejoice and blossom. It will burst into bloom - like the Havatzelet; it will rejoice greatly and shout for joy.

And as I read that verse, I realize that I’m a lot like that Havazelet, the daffodil bursting at the starting gate, always in a bit of a hurry, chomping at the bit to share joyous tidings with our darkened, wintry world.

Tomorrow, we’ll arise and realize that the hour is late and there is much work to be done. But for today, Shabbat, let us rejoice greatly in the time we’ve had and the remaining time we have. Let us count our days, stand proudly like the Havazelet, shout for joy, and party like it’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve 22,203…

I look forward to seeing you then!

* More on daffodills:

"Daffodils, That come before the swallow dares, and take The winds of March with beauty" - Shakespeare, The Winter's Tale (c. 1610-11, Axct 3, scene 3, line 118

Poem by the great Israeli poet Zelda

---------------------

Artificial Intelligence, Real Dangers

Rosh Hashanah, Day 2, 2023

Rabbi Joshua Hammerman

A priest, a minister and a rabbit walk into a bar. The bartender looks at the rabbit and says – I know why the priest and minister are here, but why you? The rabbit looks up and states, “I’m here because of artificial intelligence.”

That joke comes courtesy of John Graubard, a long-time congregant who sadly passed away in late July. John had three goals for every day: to learn something new, to help somebody, and to tell a joke. He truly understood the meaning of Psalm 90, which says, “Teach us how to count our days so that we may gain a heart of wisdom.”

“Teach us to count our days” by making each day count. John practiced what he preached and often gave me great material to use in my sermons. A few weeks before his passing, when the end was beginning to appear close at hand, I promised him that I would share one of his jokes on the high holidays. So, John, this one’s for you.

Artificial intelligence is either the greatest thing to happen to humanity since sliced bread - or it is going to lead us to extinction. Which one is it? As someone who, twenty years ago, wrote a book about seeking God in cyberspace, I feel obligated to address this question.

The first thing to note is that technological innovation is inherently neutral. It can be good, if it enhances what is real, what is human and what is truly alive, and it can be bad if it doesn’t. But it’s not inherently evil.

As the 19th century rabbi, Avraham Ya’akov of Sadigora said, “You can learn something from everything:

From the railway – we learn that one moment’s delay can throw everything off schedule.

From the telegraph we learn that every word counts.

And from the telephone we learn that what we say Here is heard There.

John’s joke points out one of the great critiques of A.I. – that too often it gets basic facts wrong. Because it lies unknowingly and does so with such authority - and because it is a machine - we tend to believe it. Of course, it’s a rabbit. Why wouldn’t a rabbit walk into a bar with a priest and a minister?! Anything else would be, as Spock would say, illogical. It’s a rabbit, just as our A.I. generated autocorrect tells us that “Nachas” is really “nachos,” ”Sabra” is “Santa,” “Boker Tov” is “Biker too,” and “Mishpacha,” perhaps appropriately, is “mishap.”

A.I. would actually be funny… if it weren’t going to destroy us all.

But aside from being funny, can it take on other overtly Jewish characteristics? Can it kvetch? I asked ChatGPT to generate a brief paragraph of kvetching, and here’s what I got.

Ugh, I can't believe how ridiculously hot it is outside. And of course, my air conditioner decides to stop working right when I need it the most. The traffic today was a nightmare, too—so many reckless drivers cutting me off and making my commute unbearable. Oh, and don't get me started on the never-ending chatter by thr water cooler and stream of emails flooding my inbox. I swear, it's like they multiply when I blink! Is it too much to ask for a day where everything goes smoothly for once? I'm just so tired of all these little annoyances piling up. Sigh.

Sigh? When did you ever hear a Jew say “sigh?” Unless we’re talking to a guy named Sy, we never say “sigh.”

And “ugh?” What Jew ever says “ugh?” It sounds like something that you would read in a comic strip – Peanuts or the Lone Ranger. And “Don’t get me started” is right out of Billy Crystal’s “Mr. Saturday Night.” And chattering? Who chatters? You chatter over finger sandwiches, made of cucumbers, and not a pastrami at Katz’s Deli. Jews don’t chatter. We kvetch!

And in order to kvetch authentically, you need to be sitting down on one of those couches with the plastic covers like my grandmother had.

So, this A.I. generated kvetch sounds about as authentic as Billy Crystal channeling Eeyore, by way of Charlie Brown. It might as well have said, “Good grief!”

Our new toy can be taken to absurd lengths. One rabbinic colleague engaged ChatGPT to write an entire Torah commentary using the styles of famous writers for each portion. Another asked ChatGPT to use the voice of the King James Bible for instructions on removing a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR.

And it came to pass. That a man was troubled by a peanut butter sandwich. For it had been placed within his VCR. And he knew not how to remove it…

Here is the complete reply...

Journalist Yair Rosenberg asked ChatGPT to do a Hillel vs. Shammai take on their classic argument about whether we should begin with one Hanukkah candle and go up to eight, or start with eight and go down – in the rapping cabinet meeting style of Hamilton. It’s really amusing - and filled with factual errors.

Here it is.

Note that the Torah says nothing about Hanukkah at all,

much less what order to light the candles.

ChatGPT will make lots of mistakes and kill you with kindness and an air of authority, so you forgive those mistakes, and eventually, as A.I. increasingly becomes the source of knowledge, displacing human sources, we start to believe that those lies are true.

It is insidious. And it is dangerous.

David Tzvi Kalman of the Hartman Institute believes that A.I. has no business writing Torah commentaries – that Torah must be interpreted and taught by humans because our sacred texts are multi layered and A.I. is shallow. But as the technology improves, as it comes closer and closer to appearing human, that could change. As Kalman states, “A.I. keeps infringing on our idea of what makes us human, and it does so by learning from humans, so undoubtedly some people will start thinking about A.I. as human.”

A.I. is built on a premise that artificiality can appear real, that a mechanical construct can fool us into believing that it is sentient. And even when it learns from its mistakes and spews out more facts, it is still fake.

We must stand up for the primacy of the real.

Religion – and in particular Judaism - has a major role to play in making sure that does not happen.

For one thing, the Torah warns us about the dangers of playing with this fire.

It’s interesting that the modern Hebrew word “artificial,” (Melachuti) comes from the biblical word “Melacha,” which means “creative work,” the kind of work done by God in fashioning the universe, and that work that was ceased on Shabbat. Meanwhile, the work done by humans who were imitating God in building God’s sanctuary in the wilderness, is also called Melacha. Melacha is godlike work, but when people engage in it in construction the sanctuary, they are not actually creating a cosmos, but an artificial facsimile of it, the shadow of a cosmos, the Genesis Creation in miniature. The name of chief artist who built the sanctuary in the Wilderness, Betzalel, actually means, “In the shadow of God.”

Melacha is what humans do when we are playing God, like angels do – and the word for angel is Mal-ach. There’s nothing wrong with imitating the divine, as long as neither we nor our creation are elevated to divine status. In fact, we are God’s masterpiece and we can’t duplicate that – and there must be safeguards to prevent us from trying.

Because it’s literally playing with fire, and kindling fire is the first Melacha mentioned in the Torah's listing of this godlike work. Starting a fire can be immensely creative or immensely destructive, and either way, that’s why it’s prohibited on Shabbat. God models for us that there are times when we must cease and desist our creative work, lest we go too far. Aaron’s two sons did just that, as Leviticus reminds us, when they were playing with “strange fire” near the sanctuary and they were consumed by it.

Perhaps that “strange fire” is artificial intelligence.

So, the first Torah lesson about A.I. is that we can generate it, but builder beware. This kind of work is so delicate that even God had to take a break from it.

If we are consumed by A.I., like fire it will consume us.

Here’s another piece of biblical wisdom related to artificial intelligence. There is a law in the book of Deuteronomy stating that we should build a parapet around our roof – a fence so that there will be no danger of anyone falling. Similarly, we need to build in many layers of safeguards on A.I.

In warfare: While the use of drones and pilotless planes has already saved lives by keeping human pilots out of the line of fire, these lethal weapons, which now are used much more frequently than manned planes, are killing many more people on the ground. We need to develop an ethic of warfare that will take the lessons of Ukraine and Afghanistan and elsewhere and apply them to a new world where it has become too easy to kill. The machines won’t become moral agents by themselves. We need to program them. That is a parapet around the roof that we need to construct.

In medicine: A.I. already has enhanced the practice of medicine and could well cure cancer. But it could also develop pathogens capable of wiping us out. When people talk of the possibility of an extinction event, the pandemic route seems to be the most pressing fear. I suppose that’s partly because we’ve proven to be so good at fighting off pandemics. Once again human beings need to create an ethical code, a parapet around the figurative roof, and to program ethics into A.I. so that an extinction level event will not be possible.

And in diplomacy: Vladimir Putin has said that whoever reaches a breakthrough in developing artificial intelligence will come to dominate the world. (He sounds more like a Bond villain every time he speaks). The race has already begun. A.I. is being used to create fake news and distort truth in the interest of authoritarian power plays. We saw just last week how the Chinese spread lies about the fires in Maui through social media, using artificial intelligence to generate fake evidence. So, this is much more serious than asking ChatGPT to kvetch. We must understand the seriousness of both the opportunity and the threat. A.I. can enhance knowledge, destroy it or subvert it.

Someone explained to me the difference between a search engine like Google and A.I. With Google it’s like having a library. With ChatGPT it’s like having a librarian. But can you entrust this librarian to write your college admissions essays, court summations and love letters? Is this a librarian who has lost a parent? A librarian who has been cheated on or sexually harassed? A librarian who has had a swastika scrawled on its front door?

Is it a librarian who can legitimately question a God that allows for thousands of innocent people to be killed by firearms each year? Is this a librarian who has seen its child wither away from Tay Sachs or Fentanyl?

No, A.I. is not a librarian. Because it is not human. I’ll keep repeating that because it needs to be drilled into us. We anthropromorphize the stock market, cars and hurricanes. But none of them has the destructive potential of A.I.

David Tzvi Kalman recently posed some key questions regarding A.I. that every rabbi must answer. I answered them.

1) Would you use A.I. to write an email to a bereaved congregant?

No. And I even have concerns about the form letters we use for Yahrzeits.

2) Can you ask an A.I. a question of Jewish law—and if you do, how should you think about the response?

No. At least not yet. I might use it to find sources where I can then check things out on my own, but I’m far from being able to trust A.I. to find the right answers.

3) Do you think it’s appropriate lay off the staff who create your newsletters and emails?

Ah, no. But this question casts a shadow over so many professions, as we're seeing right now with strikes in Hollywood and among autoworkers.

4) Can A.I. help a person do teshuvah (atone) by helping them play out difficult conversations?

Possibly. Unless that is, ChatGPT tries to break up a marriage, as happened earlier this year to a reporter for the New York Times. Finally, this question:

5) Would you use A.I. to write a first draft of your sermons?

I can promise you, that A.I. will never, ever write a High Holidays sermon of mine.

Until now!

No, this sermon is totally hand crafted and original. But frankly. I’m worried about next year. Not that you won’t hire a fine rabbi. I’m sure you will. But four sermons – that’s hard. You know, your next rabbi may have different work habits. No doubt they’ll have a different skill set, and sermon writing might not be at the top of the list. So, I’m going to help my successor out. Free of charge.

I don’t know about you, but when I was a kid and my parents went away for a few days, they would prepare a stack of sandwiches for my school lunches, wrap them in wax paper and stack them in the fridge. One sandwich for each day. Monday, peanut butter. Tuesday, peanut butter. Wednesday, peanut butter and jelly. Thursday, a Fluffernutter.

So, you know, after all these years, I’m feeling very paternal, so I thought I would do the same thing for you. I asked ChatGPT to come up with 20 sermon topics in the style of Rabbi Joshua Hammerman, and to spice up the titles with some humor. So, I’ve got, in the can, sermon topics for the next five high holidays, wrapped in wax paper and stacked in the fridge, for you to take out if you need them.

God willing, you won’t need them. Truth be told, I never ate my mother’s pre-made sandwiches. I don’t expect you to eat my sermons.

So, feel free to throw ‘em out. Because they have an expiration date. They’ll be stale and completely useless when: Democracy is safe, here and in Israel; racism is universally condemned; Jews and others can walk through the streets of THIS country without fear of hate and violent attack; when people of all sexual orientations, gender identities, races, ethnicities, religions, abilities and ages - feel valued and loved. At that point my sermons will no longer be fresh. At that point, you can throw ‘em all out.

Here are a few of the topics ChatGPT gave me.

1) Reclaiming Ritual: Because who needs a Peloton subscription when you can sweat it out during a good old-fashioned hora dance?

2) The Sacredness of Nature: Remember, hugging a tree counts as a mitzvah, as long as you ask the tree for permission first.

3) Embracing Diversity: Because no matter how you pronounce "challah," we can all agree it's delicious.

4) The Ethics of Technology: Moses may have come down from Mount Sinai with tablets, but at least he didn't have to deal with software updates.

5) Repairing Broken Relationships: Because making up with your in-laws is almost as big of a miracle as the splitting of the Red Sea.

6) Embracing Vulnerability: Remember, even Moses had to ask for directions once in a while.

You can see that the topics reflect many of my key themes. The humor? Not so much. And there definitely seems to be a Moses fixation. It's creepy how well ChatGPT seems to know me. Very creepy.

So, to summarize where we’ve gone thus far:

Judaism can help us in a number of ways, to 1) establish ethical guidelines for programming and implementation of A.I., 2) to warn us of the dangers of playing God and playing with fire; and 3) to drill into our minds the distinction between that which is Melachti – artificial – and Amiti – real. The Hebrew word for real is also the word for truth. What a brilliant concept!

When we do the ritual of Havdalah, ending the Shabbat, we focus on how Judaism makes distinctions, between the holy and secular, darkness and light, between Shabbat and the other days of the week. We need to create some ritual that will help us do the same with this new technology, to heighten our sensitivity to the fine line – which is becoming less distinguishable all the time, between synthetic and sentient, between reality and virtual reality, between intelligence and artificial intelligence. And as Deuteronomy commands, we must always choose the living over the artificial. We must choose life. We need to keep reminding ourselves that human life is unquantifiable, while machines are only quantifiable. Machines do not have souls.

Maybe that ritual would be to include Psalm 90 in our prayers. “Teach us to count our days that we may gain a heart of wisdom.” Teach us how to count wisely, by counting rarely, by putting numbers in their proper place. Never choose quantity over quality, metrics over mortality. No algorithm should be able to diminish the majesty of personhood and the infinite value of human life.

Actually, Psalm 90 is already in our prayerbooks, and is recited in the introductory Psalms section. But here’s something interesting. It’s not in that section on weekdays. Only on Shabbat, the day when artificiality, Melacha, ceases. When God rests from creating – and we rest from counting.

Artificial intelligence and the virtual world are based on algorithms and probability, as measured in combinations of 1’s and 0’s. But personhood is based on the beat of a human heart (and as a reminder, for Jews, a person is considered fully human only at the time of birth). We can interpret Psalm 90 this way: Teach us to count wisely, as filtered through the life-rhythm of a beating human heart.

You know, just this summer, the mass murderer of Jews at the Tree of Life synagogue was given the death penalty. Now Jewish law frowns on capital punishment, because you can’t put a value on a human life, even the killer's. To destroy a life is to destroy the world. While I can make a case in Pittsburgh for capital punishment – the Talmud states that those situations must be so rare as to be almost nonexistent.

But there is another aspect to this, which was brought out by writer Mark Oppenheimer. Eleven souls were taken from us that Shabbat and they are irreplaceable. And not merely as numbers in a minyan. Not only did they make the minyans – they were the regulars. They were the ones who came early, who prepared the kiddush, who welcomed those who might be strangers or people so unfamiliar with Jewish ritual that they actually came on time. These people are the stuff of community. True heroes. The Pittsburgh gunman didn’t just kill 11 Jews. He killed a minyan.

We need ten for a minyan. But when we count a minyan, we say, traditionally, “Not one, not two, not three.” Because even when we need a specific number of people, we never reduce people into becoming specific numbers – we never assign their personhood a value that is less than infinity.

In the Talmud, (Yoma 22b) Rabbi Eleazar says: Whosoever counts Israel, transgresses a [biblical] prohibition, as it is said (Hosea 22:1): ‘Yet the number of the children of Israel shall be as the sand of the sea, which cannot be measured.’”

The commentator Rashi explains that “the evil eye has power over numbered things.” So the custom developed to try to avoid spotlighting individuals whenever counting them – even for something as important as a minyan.

Counting standardizes human beings. It creates a sameness, sets boundaries that objectify and limit us. Assigning people numbers dulls the spark of divinity within them.

All our days, O God, teach us how to count properly. Numbers reduce us – we become basically the same.

We become things.

It is 60 years since the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote his Letter from Birmingham Jail. That milestone last spring coincided with the 100th anniversary of Martin Buber’s book, I and Thou. “Segregation,” King wrote, from solitary confinement, “substitutes an ‘I it’ relationship for an ‘I thou’ relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.”

In 1967, Martin Luther King called for a “Revolution of Values.” He said, “We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

Just as everything in the past 80 years was tainted by the lurking potential for nuclear annihilation, so everything now is tainted by the growing shadow of artificiality. The digital age, which held such promise, has turned out to be a Trojan horse. We are in a gargantuan struggle to reestablish the preeminence of the real.

You know that according to Jewish law we are not supposed to throw out a book with the sacred Hebrew name of God in it. But God’s name can be erased on a computer screen. Why? because it never was really there in the first place. “The letters on a computer screen are an assemblage of pixels, dots of light, what have you,'” a rabbi explained. “Even when you save it to disk, it's not like you're throwing anything more than a sequence of ones and zeroes. It's there, but it really isn't.”

It’s not real.

Many of us take photos with our phones and the photos have gotten especially sharp in low light lately. Unless you face happens to be of a darker pigmentation. That’s because our phones were programmed with lighter faces in mind. The photos we are seeing, as lovely as they are, contain a built-in racial bias.

The pictures are not real.

Those of you watching us online right now are having a real experience – and Zoom services basically saved us during Covid – but only because the communication is from human being to human being. From me to you. “The voice must the voice of Jacob,” and not Jacob’s avatar. Similarly, social media can enhance life-affirming, I-Thou relationships, but only if being online leads us beyond the shallowness of simply tallying up “likes” and generating friend requests.

At its worst, it ruins lives with gossip and cyberbullying, leads to loneliness and suicide by setting up unreasonable expectations of success and body image and it turns us into one dimensional robots who all seem to be doing the same things at the same times, though in different places, cropping the same photoshopped images that are filtered and primped until they are grotesque imitations of what is real, and revealing too much information that is really not information at all, but spin.

Megan Garber of the Atlantic wrote a cover story in March, entitled, “We’re Already Living in the Metaverse,” which argued that reality has become distorted by our pathological need to be entertained. As Atlantic editor Jeffrey Goldberg describes it, “Megan examined society’s addiction to illusion and trivia and cited the great dystopian writers of the recent past, who warned that ‘we will become so distracted and dazed by our fictions that we’ll lose our sense of what is real.’ The result, Megan wrote, “will be a populace that forgets how to think, how to empathize with one another, even how to govern and be governed.”

Think how our lives have been digitized. In the NFL, on each play, Next Gen Stats updates its database every 100 milliseconds from radio frequency ID chips in the players’ shoulder pads, giving them all 22 players’ position on the field, along with their speed, acceleration, running direction, and body orientation. The game has become essentially a video game where the players are viewed as very agile sacks of meat in colorful gladiator uniforms.

But something happened this past January to jar us back to reality. A player’s heart stopped beating on the field. Buffalo Bills’ safety Damar Hamlin nearly died.

For most fans, injuries on the field moments are usually a good opportunity for a quick bathroom break, or a chance to zap some nachos. Catastrophic injury has been woven into the banal routine of sports viewing.

No one grabbed for the nachos that Monday night. And those who did out of Pavlovian habit, had to wonder, at least for a millisecond, What am I doing??

Back in the 1960s, Abraham Joshua Heschel asked whether religious leaders forfeited the right to worship God because we’ve knowingly, and with intent, brought pain and humiliation to fellow human beings by treating them as commodities, as numbers, as things. In the National Football League that happens every day. They are well paid commodities. But that’s what the players are.

The Damar Hamlin injury reminded us that human beings are of infinite value and complexity. But will that incident be a game changer? Will these gladiators become pieces of meat again in our eyes. The next time we see a bone-crunching hit, will we be calmed by the announcer’s softening euphemisms like, “he was dinged up.”

Yeah. Dinged up. So was Dresden.

As our world careens from one radical change to the next, this is our moment of truth. We need to cling to what is human and what is real, or we may lose it forever.

For in fact, artificial intelligence as just a very large and dangerous tip of a much larger iceberg.

That is the battle of our times. We are reinventing God’s universe in miniature, but the result is only a shadow of God’s true reality. And in the process of giving ourselves over to our own creation, we are losing ourselves.

Martin Buber tells the story of the Hasidic Rabbi Zusya of Hanipol On his deathbed he began to cry uncontrollably, and his students and disciples tried hard to comfort him. They asked him, “Rabbi, why do you weep? You are almost as wise as Moses, you are almost as hospitable as Abraham, and surely heaven will judge you favorably.”

Zusya answered them: “It is true. When I get to heaven, I won’t worry so much if God asks me, ‘Zusya, why were you not more like Abraham?’ or ‘Zusya, why were you not more like Moses?’ I know I would be able to answer these questions. After all, I was not given the righteousness of Abraham or the faith of Moses, but I tried to be both hospitable and thoughtful.

But what will I say when God asks me, ‘Zusya, why were you not more like Zusya?’

I first encountered Martin Buber’s I and Thou in college, in a class that changed my life, which was taught, ironically, by an applied mathematician who was also a great humanist, Professor George Morgan, who died this past February at the age of 98. It’s all about being true to who we are, so that we might reach out and meet our neighbor with complete authenticity. Relationships and professional roles cannot be contrived, fabricated, planned, calculated, or programmed. True relationship cannot be “artificial.” Paradoxically the most difficult of all things to achieve, is to be, simply, oneself.

To have known me here for these past 36 years is to know that I have always looked at religion from the prism of the humanities, not as doctrine but as lived experience, not as something supernatural but something very down to earth, a product of the human condition and a contributor toward human flourishing.

Lo Bashamayim hee – it says in Deuteronomy. “It’s not in the heavens.” “This thing is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart.”

Religion is right here – in your heart. That’s what’s real – and our sacred wisdom reminds us of precisely that.

We are not in the business of keeping a dying religion on life support just because it’s been around for a few thousand years and some people feel guilty about eating a lobster roll. It’s been around so long because it helped human beings who happen to be Jewish to become better human beings. It has helped us to make the world a better place. To be Jewish, in other words, is to be fully human. To be fully human is to be fully engaged with the universe and with the epic saga known as life.

Perhaps we’ve grown to intuit this difference between the virtual and the real. Perhaps that is why people keep on coming back to their houses of worship, to find guidance as we engage in God’s sacred Melacha. If we can be the locus of the real, that point of light where “I” meets “Thou,” we will be fulfilling a sacred mission that we are uniquely qualified to do.

And perhaps that, in the end, will save us.

I’ll take you out with another joke from John Graubard, of blessed memory, because John deserves an encore. He sent this one to me a couple of years ago.

A Buddhist monk goes to a (kosher) hot dog vendor and says, “Make me one with everything.”

The vendor hands him a Hebrew National hot dog on a bun with mustard, ketchup, relish, onions, and kraut. He then says, “That will be four dollars.”

The monk hands the vendor a $20 bill. The vendor puts it in the cash box but doesn’t give anything back to the monk.

The monk says, “Don’t you owe me something?”

The vendor replies, “Change must come from within.”

Teach us how to count our change from within, O God. But teach us that the world of counting is not the ultimate reality that we seek. Not the weekday, secular world of artificiality and melacha, but the world of relationship, of humanity, of holiness and of Shabbat peace.

Teach us to count correctly, that the world might beat to the throbbing of a human heart, so that we may gain true wisdom, and an intelligence that is anything but artificial.

Teach us to distinguish the holy from the mundane – and the fake from what is truly real.

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment