Counting to One

Kol Nidre, 2023

Rabbi Joshua Hammerman

Five Jews were playing poker one night when Meyerowitz loses $500 on a single hand, stands up, clutches his chest and drops dead on the floor.

Bash looks around and asks "Now, who is going to tell the wife?"

They draw straws. Nordheim, who is always a loser, picks the short one. They tell him to be discreet, be gentle, don't make a bad situation any worse than it is.

"Gentlemen! Discreet? I'm the most discreet mensch you will ever meet. Discretion is my middle name, leave it to me.

Nordheim schleps over to the Meyerowitz apartment, knocks on the door, the wife answers, asks what he wants.

Nordheim declares "Your husband just lost $500 and is afraid to come home."

She hollers, "TELL HIM HE SHOULD DROP DEAD!"

Nordheim says, "I'll tell him."

Sometimes there are ways to soft pedal bad news. It’s not so easy today.

Today we are marking, on the Jewish calendar, the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. In Israel, this is a time of profound reflection and concern. In fact, there are some parallels between that week in 1973 and how Jews feel right now. Back then, as the war began, reports from the front were patchy, but word was getting around. Israel was in real peril. The Egyptians had broken through in the Sinai and the Syrians in the Golan. The Syrians had a clear path to cut the Galilee in two, which would have effectively been the end of Israel. It was only through the extraordinary courage of Israeli tank crews and some dumb luck that the state survived. Just long enough for the IDF to turn the tide and the Nixon administration to come through with much needed assistance.

Fifty years ago, Israel survived a truly existential threat. An external threat.

There’s another anniversary that we are commemorating this month. Thirty years ago, the first Oslo accord was signed on the White House lawn. At the time, many thought it would be a turning point in history. It was, but not in a good way. It led to another existential moment that nearly tore Israel apart from within - the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin two years later, followed by the second intifada. So, these are sobering anniversaries.

Especially because Israel faces an existential threat today as well. Several, really. But none more than the judicial reforms that are being promoted by the most extremist government in Israel’s history. There is legitimate concern that Israel’s future hangs in the balance. In the opinion of two thirds of the population, there is a real chance that this will end up in a civil war. In a survey this summer, fifty-eight percent of Israelis believe that 'Israel is on the verge of economic, social, and political collapse' because of the judicial overhaul.

And that’s where the parallels between now and 1973 diverge. Back then, the Jewish world rallied behind a slogan that would seem ludicrous now:

“We are One.”

Teach us to count our days, says Psalm 90, that we may attain wisdom. But right now, the Jewish people can’t even count to one. Who knows one? We certainly don’t. We don’t know it as Jews, and we don’t know it Americans either. The concept of “unity” has gone the way the dinosaur.

For the first time in all my years in the rabbinate, I see the real possibility of an irreparable rupture.

I don’t think most American Jews have any idea of what our Israeli cousins have been going through this year and how there is a real fear that they are teetering on the precipice of a non-democratic theocracy.

It truly is remarkable what this grass roots movement has accomplished, led by distinctly apolitical figures like Shikma Bressler, a physicist and mother of five, who has emerged as a symbol of defiance of the government’s judicial overhaul. She is decidedly not a politician. And she’s decidedly not left wing.

And neither are the protests, which have adopted as their rallying symbol, of all things, the Israeli flag. At these protests participants span the full diversity of the Israeli people – Jewish and Palestinian, religious and secular, gay and straight, Ashkenazi and Mizrachi. And everything in between. They all understand what this is about. An independent court is all that stands between a moral society aspiring to protect human rights, however imperfectly, and an extremist agenda supporting the visions of Meir Kahane, Baruch Goldstein and Yigal Amir, the three most notorious Jews in the history of the state, all of whom were celebrated with signs at a pro government rally this month.

When Betzalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben Gvir were invited into positions of power, it was the equivalent of bringing the KKK into the US cabinet. And then the decision was made to remove the one remaining obstacle preventing them from doing whatever they want. There is no real check on the government other than the judiciary.

In April, Justice Minister Yariv Levin admitted that elements of his plan would “end democracy” because it would essentially give the coalition unfettered power. Levin’s admission, with the country already seething, confirmed the suspicions of many that this had never been about fine-tuning the judiciary. It was a project much more nefarious. So that’s why these unprecedented protests are happening. Let me explain why they matter to us.

In the words of Yuval Noah Harari, the mega best-selling author of “Sapiens,” “Imagine a world in which “Judaism” becomes a synonym for religious fanaticism, racism and brutal oppression. Could Judaism survive such a spiritual destruction?”

That is the world that would inevitably result from the dismantling of judicial checks and balances.

Another columnist, B Michael, known as Israel’s most sardonic commentator, puts it in even more startling terms. Diaspora Jews, he writes, should not consider Aliyah.

My dear Diaspora brothers, the torch is being passed to you. From now on, you are the keepers of the flame. You are in charge of proving the existence of a sane version of the Jewish people. You are responsible for maintaining a rendering of Judaism that is not shameful.

Are you shocked yet? For the most part, unless you immerse yourself in Israeli media like I do, or read Thomas Friedman religiously, you can’t grasp how dire this moment is.

If you aren’t paying attention, you don’t realize that this is not a panic-stricken hyperventilation by Israel’s left. You just need to follow what this government is saying in Hebrew, where it talks less about Jewish security and more and more about Jewish supremacy. It cozies up to illiberal extremists in Romania, Hungary, Turkey, Poland and of course here. Even with Iran presenting a grave danger, setting up attack bases within several miles of Israel’s northern border, the government forges ahead with a plan to curb the courts and subvert the media, all with their eyes on a bigger prize of annexation, theocracy and driving the Arabs out.

But there is hope. And that hope resides in the spirit of the people, who have taken to the streets every week for this whole year. Thomas Friedman, who has witnessed all the great democracy protests of the past half century, from Beirut to Berlin, from Moscow to Cairo, from Hong Kong to Kyiv in 2014, wrote in Ha’aretz:

But I have never seen something like the Israeli democracy protectors’ movement. More than a half a year of tens of thousands of people – center-left and center-right – coming from a broad swath of the population, turning out every Saturday night to resist a judicial coup, and managing to appropriate the national flag and the national anthem as their symbols.

He prodded American Jews to do something we really don’t like to do, and that is choose sides.

Yuval Noah Harari speaks of two kinds of Judaism, symbolized by the two most noteworthy Jews alive today, whose paths crossed at the UN this week. There’s Netanyahu Judaism, and there’s Zelensky Judaism: Zelensky, who lives in a place where Jews have often faced grave danger, is never ashamed to call himself a Jew. But he's also proud of his Ukrainian nationality. Fearless, human, relatable, he looks at the world in a very Jewish way, pursuing justice and fighting corruption and hate.

Harari points to Huwara, the West Bank village attacked this year following a terror incident where two Jews were killed at a gas station - and it should be noted that there have been an increasing number of terror attacks perpetrated against Jews, many instigated by Iran. But the reprisal was shocking. Following the attack, Israel's new far-right Finance Minister, Bezalel Smotrich -- now with new authority over the West Bank -- stated "I think the village of Huwara needs to be wiped out. I think the State of Israel should do it." That is the quote. Scores of Israelis took revenge on the entire town in a night-long rampage, setting dozens of cars and homes on fire, and the police and army were nowhere to be found.

A video went viral, where a crowd of Jews stood in ecstatic prayer while staring at a building in flames.

It has been compared to a pogrom, and not without reason. And that Kaddish that they were reciting on the video - not the mourner's Kaddish, I should add - is the very definition of a Hillul Hashem, the profanation of God's name.

“It is a historical irony,” Harari wrote, “that just when in Huwara, Jews are behaving like Cossacks, in Ukraine the descendants of Cossacks have chosen the Jewish Zelensky to lead them at their moment of ultimate crisis. Zelensky’s Ukraine proves to the world that patriotism, democracy, Judaism and commitment to universal values get along fine together.”

Harari believes that Zelensky’s Judaism is closer to our Judaism than Netanyahu’s. I’m inclined to agree.

For one thing, only one of these two leaders is on trial right now for bribery, fraud and breach of trust and it ‘aint Zelensky, who is trying to root out corruption, even in the midst of a life-or-death.

But many in Bibi’s own party are now seeing the light and were elections held today, this radical right coalition would be booted out.

Israel belongs to all the Jewish people. It is ours to shape and critique and protect. For the first time, Israelis who typically have asked diaspora Jews to butt out of its internal affairs are begging us to come to be active participants. And we should. This is an internal struggle – and we are part of the family.

Last Rosh Hashanah I gave a sermon on how we need to love Israel as one would love a family member, indeed as we have always loved America, despite this country’s shortcomings. I talked about the song, “En Li Eretz Acheret,” “I Have No Other Country,” which was once again this year voted one of the top songs of Israel’s 75-years, and it’s become a theme song of these protests. It’s an all-purpose song for rough times and by singing it people are proclaiming that they are not giving up.

We cannot give up either. I’ve stood here countless times talking so lovingly about Israel, and I love it not one iota less than I did when I arrived. But when elements within the government of Israel are on the cusp of doing something so duplicitous, so dangerous, so hateful, so power hungry and so anti-democratic, we have to stop making excuses for it. And we have to insist that our American Jewish organizations stand up for democracy at the hour of greatest need. As Daniel Gordis, who has usually defended Netanyahu, said recently, one day, grandchildren will ask their grandparents what they did right now to save Israel’s democracy. We have to speak out.

Teach us to count our days, by teaching us how to stand up and be counted, to be courageous and never be afraid.

We have to love Israel – as well as the US – enough to want them to be better.

And we want them to be united. To be One. Teach us, O God, to learn how to count to One.

Who knows one? American Jewry has never truly been united, regarding Israel, or much of anything else. But sometimes we need to divide in order to unite.

We must cultivate our own brand of Judaism. Not the Netanyahu brand, to be sure. But not the Zelensky brand either, which out of necessity has lost much of its Jewish content, though we’ve begun to see a renaissance of Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

We need to be bold in cultivating our own brand of Judaism here in America – here at Beth El – a Judaism steeped in values of menschlichkeit, enriched by our history, inspired by the resilience of prior generations, humbled and steeled by the Holocaust, seasoned by American pluralism and religious diversity, challenged by intellectual honesty, and the clarion call for social justice. Very serious but also a whole lot of fun. And proud, proud, proud. That’s TBE Judaism as we have envisioned it over the decades. That’s the vision I’ve tried to propagate. And that’s the model that we still need to present to the world.

Gone are the days when Israelis smugly would say, as the Novelist AB Yehoshua once did, that American Jews only “play with Jewishness,” while Israelis live it every day. Yes, they do live it every day, and they aren’t doing a very good job of it. But we are no longer on the sidelines of the struggle to build a Jewish future. We’ve begun playing some home games in our own sandbox. And we’ve gotten pretty good at it.

By separating ourselves from a distorted, bizarro version of Judaism, we can help forge a Judaism that can help secular and traditional Israelis to see that Huwara is not the only option.

Israelis and American Jews need to understand that, by some miracle, the Jewish people returned to their homeland after 2,000 years and at the exact same time created the most successful diaspora community ever. And now we can help strengthen their vision by unabashedly proclaiming the vibrancy of ours.

And that’s how division will help heal the breach. By being two proud communities, we can forge one Jewish people.

One plus one equals one.

Despite all that has torn us apart, I remain optimistic. Here are some examples of why.

On a What’s App group, someone asks to borrow an Israeli flag for a pro-reform rally in Jerusalem to be held on a Thursday night. Someone replies, “Sure, no problem,” but he needs it back for the anti-reform rally to be held right after Shabbat. “Of course,” replies the guy and says thank you.

Only in Israel! Because beneath all the acrimony, we are family. And beneath all the seething anger, we are part of the same mishpacha.

One of the brilliant moves of the pro-democracy camp has been how it reclaimed the Israeli flag from the right wing. For years, the message to people on the center-left was that they were not true patriots. But as one protest organizer says, “Our flag is blue and white, and we’re not going to let anyone take it from us.”

Now everyone is patriotic. Everyone waves the flag; though for Palestinian Israelis it’s a bit more complicated. But unity is more conceivable when you are embracing the same symbols. Visually, you can’t always tell which side is marching.

And there was this other incident this summer that was widely publicized.

It was a brief but touching moment, captured in a video clip taken at Jerusalem’s Yitzhak Navon Train Station.

The clip showed protesters crowded on the long escalators at the station. Those who had been at the massive anti-reform demonstration in Jerusalem were descending to the platforms leading away from the capital, and those coming back from the large pro-reform rally in Tel Aviv were ascending on their way back.

There were more kippot among the government supporters and more T-shirts worn by the overhaul’s opponents. But the two groups resembled each other in many ways, including their passion and concern for the country – and everyone was carrying the Israeli flag.

Suddenly, as the two sides headed in different directions, people began reaching out across the divider and shaking the hands of those passing on the opposite escalator. How cool is that?

There is – in the end – hope that we can count to one – that there is much more that unites the Jewish people than divides us.

I’ve been focusing on Psalm 90 this week, but I’d like to take a quick look this evening at Psalm 133, which might have a familiar ring to it.

שִׁ֥יר הַֽמַּעֲל֗וֹת לְדָ֫וִ֥ד הִנֵּ֣ה מַה־טּ֭וֹב וּמַה־נָּעִ֑ים שֶׁ֖בֶת אַחִ֣ים גַּם־יָֽחַד׃

How good and how pleasant it is

that kinfolk dwell together.

The rest of this short psalm is filled with vivid imagery. It speaks of oil flowing on the beard of Aaron the high priest, and the dew from Mount Hermon falling on the mountains of Zion, a place where God ordains blessing and everlasting life.

Let's take a closer look:

First of all, what is the proper melody for the first line, Hinay mah tov? Some of you may know (slow melody). And there’s also… In fact, there are dozens and dozens of melodies for the same verse. I’ve collected over thirty YouTube clips into one posting - you can access the videos here. They span the spectrum of Jewish cultural expression through the ages and across the world, from Hasidic, to modern Israeli to Reform, to Renewal, to Sephardic and Mizrachi, to Leonard Bernstein’s classical Chichester Psalms, even Harry Belafonte, who passed away this year. What I couldn’t find online was my old USY call-and-response – great for long bus rides.

But here’s the point – the words are the same. Exactly the same. Our spirits are stirred by precisely the same three-thousand-year-old words, just with different melodies.

And the sentiments are the same. Jews really do idealize unity. We want to get along. I agree with very little that far right Israelis say, and they want to delegitimatize me as a Conservative rabbi – but I know that the Ultra-Orthodox are especially terrified of Israel being split into two countries, as is now being discussed – quasi seriously by some. It would not go well for their half, the half with no army, no economy and no allies. But God will provide…

Down deep, the people want unity, that’s half the battle.

But unity with whom? Achim, says the Psalm. Shevet Achim.

In modern Hebrew the expression Achi is like the English “Bro,” - a comrade in arms, someone who fought alongside you in a war. More than a friend; achi is someone you would lay down your life for, because in the IDF it's quite possible that someone next to you in the foxhole already has done that for you.

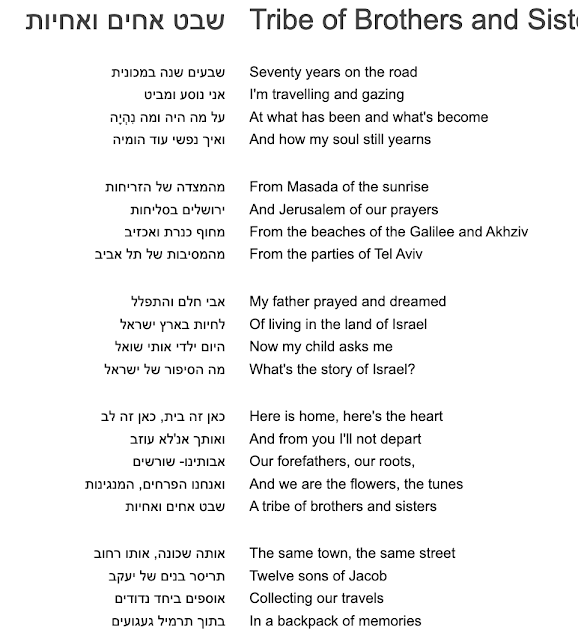

The word shevet means to dwell, but it evokes also the word for tribe. When Israel turned 71 a few years ago, a very popular song went viral, inspired by Psalm 133. It’s called “Shevet Achim V’Ahchayot,” “a tribe of brothers and sisters.” The song was written by Idan Raichel, who is Israel’s poster boy for diversity. And it’s sung by 35 of Israel’s best-known musicians.

A country that adores Idan Raichel - and Israelis do - is not a country headed for civil war.

I read a really nice Buddhist perspective on this psalm –The unity spoken of here transcends emotion, suggesting a belief that everybody counts, everybody matters, without your necessarily having to like them. We don’t always like our siblings, even as we love them.

As this commentary states, “The cultivation of lovingkindness leads to a bone-deep realization that our lives have something to do with one another, that the constructs of us and them, are just that: constructs. The deeper reality is ‘we.’”

Psalm 133 goes on to flesh out that notion of unity and love with distinct images. One is of Aaron, the high priest, being anointed with olive oil – the olive branch being a symbol of peace. It’s a reminder that Aaron himself is a symbol of peace in our tradition. He tried to find common ground at the Golden Calf and he was the middle man in Moses’ diplomacy with Pharaoh. Pirke Avot states, “Be like Aaron, who loves peace and pursues peace – rodef shalom.” It’s not enough to love peace in the abstract. You have to actively make peace, one person at a time.

According to a midrash (Kalah Rabati 3:2), when Aaron heard that two people were fighting with each other, he would go to one… and then to the other…. Shuttle diplomacy, long before Kissinger. When the two combatants would meet on the road, one would say to the other, "Forgive me for the offense which I did to you" and the other would say the same. Who knows what Aaron told them that could flip things so dramatically. Aaron is a role model for reconciliation.

The psalm also speaks of dew running from Mount Hermon to Mount Zion. This is one of the Psalms of Ascent, shir ha-ma’alot – sung by pilgrims heading to Jerusalem, to Zion. Mt. Hermon is at the northernmost point of the country, on the border with Syria and Lebanon, 250 miles away, about as far from Jerusalem as you can get and still be in the country. And so, in ancient times, as pilgrims made their way toward Jerusalem, they would start up near Tel Dan way in the northern Galilee and pick up more people along the route. This was a long trek. So, plenty of time for a very diverse group to iron out their differences. A brilliant way to bring people together.

And in ancient Israel, north and south were bitter foes, like the north and south in the US.

But here, together they would sing this song of love and sweetness, of dwelling in common quest, wending their way from the top of the country to the bottom, from one end of the land to the other, from Boston to Charleston, as it were. All the while, singing Hinay mah tov

I remember singing Hinay Mah Tov in late 1987, when I had just arrived here and I participated, along with a dozen bus loads that left from the JCC, in the great March on Washington for Soviet Jewry. It changed history and we were there - together - on pilgrimage to the capital.

The song, and the walk, in ancient Israel and modern America, brought opposing camps together, to become one tribe.

And then, they would arrive at Zion.

Rabbi Marc Gellman asks us to imagine being “on one of these holiday pilgrimages, thousands of pilgrims camped on the hillsides around the great Temple in Jerusalem. Thousands of campfires, and the sound of singing and dancing. All vengefulness forgotten. All tribal conflicts forgiven. Each family a part of a larger fire and a larger holiness. Such a gathering, such a vision is described by the psalmist as being both “good” (tov) and pleasing to the senses (naim). It is good because the highest being deserves the highest praise, and it is pleasing because just for a brief shining moment we are all one. We are not divided. We are not at war. We see in our neighbor the source of our fulfillments, not the source of our limitations. Such a dwelling together for God is both a memory and a dream.”

The ancient pilgrimage festivals were like a week of free therapy. A chance to come together and celebrate what unites us rather than what divides us. These days there are few events that can do that. Happenings like Burning Man or a Taylor Swift concert. In Israel, music a is real unifier. Israelis love a good singalong. And Hinay Mah Tov has served that purpose for three thousand years.

There’s one more question that jumps out about this Psalm. It has to do with the first word. Why doesn’t it just say “Mah tov?” “How good!” You don’t need the Hinay. It’s already good. It’s good for people to be together. But why “Hinay?” Behold! Lookie here!

Is God saying it?

OMG! Hinay - My kids! They are actually getting along! I love it when that happens!

Or maybe the psalmist is echoing what Abraham said when God called him to ascend to that same city. Henayni! I’m here! Abraham replied. Count me in! I am here for this pilgrimage. I’m not just a detached observer from the outside. I’m a participant. I’m here on Kaplan Street in Tel Aviv. I’m here before the Supreme Court and the Knesset. And I’m here at Temple Beth El on Kol Nidre night.

We are all in!

And, to quote the Leonard Cohen song, Who By Fire, inspired by the liturgy of the High Holidays: Who shall I say is calling?

A thousand generations are calling. We have a homeland. We have a vibrant people. We have two vibrant homes. And these homes have been entrusted to… us!

We have diverse ways of being Jewish, and of singing this song. The melodies are dramatically different. But the words are exactly the same.

Behold, isn’t it wonderful and pleasant for us to dwell here together, as one. Even if the Jewish people are not really one, we can still imagine it. Sometimes a hopeful vision is all we’ve got.

And sometimes, a hopeful dream is all we need.

Thirty years ago, the tribes of Israel and the tribes of Ishmael met on the White House lawn on a beautiful mid-September afternoon. As Eric Alterman put it in his book, We are Not One, many “Jewish tears were shed, including my own, on the White House lawn that day, when, during Rabin's speech, The usually blunt, unsentimental, ex general, cried out to the Palestinian people.

We say to you today in a loud and clear voice: Enough of blood and tears. Enough. We have no desire for revenge. We harbor no hatred towards you. We, like you, are people who want to build a home, to plant a tree, to love, to live side by side with you in dignity, in empathy as human beings.

A far cry from Betzalel Smotrich and the incitement of Huwara Judaism.

And where have I heard those words before? Live side by side…. Shevet achim gam yachad. We’ll dwell as brothers and sisters – we’ll live alongside you – but not just as estranged neighbors, not in a cold peace, not to burn down your villages and chase you away – but in empathy, in dignity, as human beings. And you will treat us the same way. GAM yachad. Also in unity. Also, GAM, also, you and also me.

We’ll live as neighbors, as family, in unity, as One.

It takes two to become one.

One plus one equals One.

Those words of Rabin’s may have been naïve, and they may have been illusory, not because they could not have borne fruit in a better world, but because bad actors were determined to make sure they wouldn’t. Many people would die after Oslo, on Egged buses, at the Dolphinarium disco, at Cafe Moment and Cafe Hillel and Hebrew U’s cafeteria and Sparro pizza and in Jenin, Ramallah and Palestinian refugee camps. And Rabin himself, like Sadat before him, became a martyr to hope, with a bloodstained song of peace in his pocket. And every time someone makes a bold move for peace and unity, someone else tries to blow up those dreams.

But we can never stop dreaming. For these dreams reflect the real Israel that I grew up believing in, the real Israel of the protesters today, the real Israel that can yet come in to being – the real Israeli government that existed just a year ago and can again – a true unity government. It reflects the real Judaism that American Jews and Israelis can share. And it reflects the real America too.

As divided as Israelis seem to be, and Americans too, the people are not as divided as the politicians. In both countries, the vast majority cherishes democratic values. We can build unity from that foundation.

“We can either fall into a very dark, extreme, racist place where the Israel that we know, in all its social and economic aspects, will be destroyed,” says Shikma Bressler, one of the leaders of the movement, the physicist who is not a politician. “Or we can build a new, stronger, better democracy for the good of all the people.”

As Elie Wiesel said in a speech delivered a couple of months after the 1973 war and a half century before the current Russian war on Ukraine:

Never before have Jews been so organically linked to one another. Shout here and you will be heard in Kiev. Shout in Kiev and you will be heard in Paris. When Jews are sad in Jerusalem, we are moved to tears everywhere. Thus, a Jew lives in more than one place, in more than one era, on more than one level.

Wiesel’s vision may never have been realized, except perhaps for those days and weeks in 1973, when Jews everywhere came together – including in this newly-opened, carpet-less sanctuary, and spontaneously emptied their hearts and their pockets. It happened then, and it may be happening right now, this year, in the streets of Israel. A true unity might yet be forged. We cannot give up that hope. Nor can we afford to be late to the game. Hinay Mah Tov – how wonderful they are – our Israeli achim, who have taken to the streets in song and dance, and even are capable of reaching out to those who oppose them, who for now are still on the other side of the escalator. And they are waiting for us to join them.

Who knows One? We know One. Teach us, O Adonai, to count to One.

No comments:

Post a Comment