MORE ON “FLIPPING THE SCRIPT”

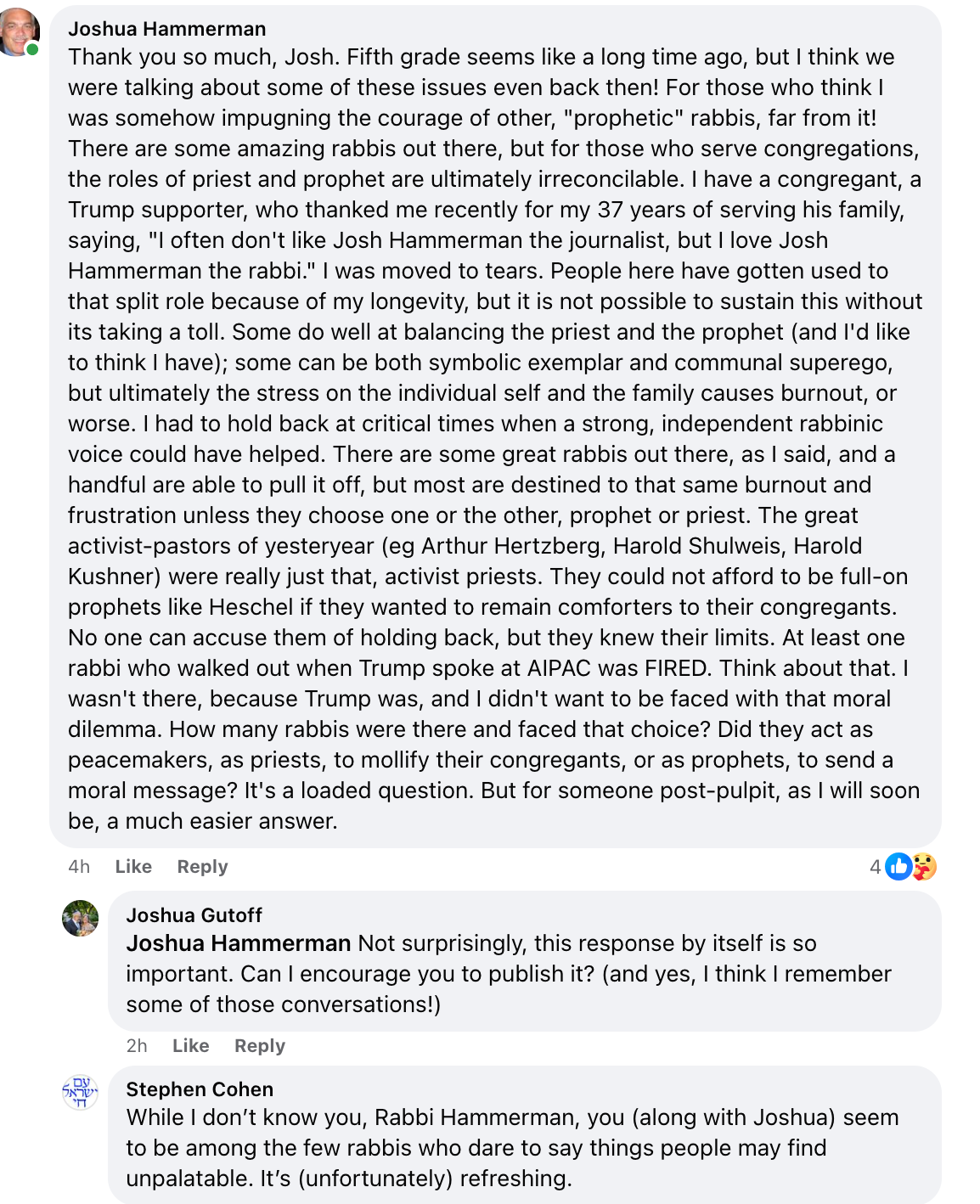

Some follow up from last week’s essay, ”Flipping the Script.” It has received inordinate attention over the past few days, including an exchange on Facebook when the article was shared by an old friend, Rabbi Joshua Gutoff, who wrote this:

What follows is a dialogue of the precise sort I was hoping to inspire, with some of Josh’s friends, including rabbis, discussing my claims that the two main roles of a rabbi, priest (pastor) and prophet, are at their core irreconcilable.

So here’s what I wrote to respond to those comments and others along the same vein. Although just a Facebook post, I believe it’s an important addendum to what I wrote last week and helps clarify the issues.

AFTER AUSCHWITZ: DO RABBIS MATTER?

After Auschwitz (also the title of Richard Rubenstein’s most famous book), everything changed for Jews, only it may have taken time for those transformations to appear. I discuss this in detail in my 2020 book Embracing Auschwitz: Forging a Vibrant, Life-Affirming Judaism that Takes the Holocaust Seriously, published by Ben Yehuda Press.

Now those changes are clear to see, as the trauma of the Shoah has blended with other social, economic and environmental forces to forge a Judaism that is almost unrecognizable in comparison to the ways Jews lived just a generation ago. And this cuts across the board, from secular to Haredi. Unrecognizable and irreconcilable. The center cannot hold.

And it begins with the role of the rabbi, which has changed dramatically since I was ordained in 1983.

Two weeks ago, a famous rabbi died. His name was Fred Neulander, and 25 years ago he was convicted of hiring a hitman to murder his wife. Actually two hitmen. He died while serving a 30 year prison term in Trenton, N.J., not far from where he was a celebrated and successful pulpit rabbi, in Cherry Hill.

In 2000, I wrote about Neulander and what his story tells us about the American rabbinate. Why was his story such a cause célèbre, to the point where an author received “a significant six figure” advance for the book about the crime? Is it because ostensibly he was the first rabbi ever to be charged with murder? Or is it because people look for ways to erect pedestals to build up their rabbis, only to secretly seek any opportunity to knock them down?

For in fact, by the turn of this century, rabbis were already becoming stunningly irrelevant to people. I quoted a June, 2000 study by Bethamy Horowitz showing that only 5% of American Jews saw their rabbis as a positive influence in their life, while 10% said rabbis had negatively influenced them. The remainder of those surveyed didn't mention rabbis as an influence at all, positive or negative. For rabbis that was a striking indictment: It meant we were 85% irrelevant. That statistic screamed out for some major rethinking of the rabbi’s place in modern Jewish life. Personally, if my work was to be irrelevant to 85% of American Jewry there was no reason for me to be missing my kids’ school plays and Little League games. If I was to be an invisible rabbi, I might as well have tried to be a better father.

Now, a quarter century later, I can look back at my years in the pulpit and feel some satisfaction that, at least in my little corner of the sky, my relevance score was quite a bit higher than 15 percent. I know that anecdotally, and also intuitively, and if not, I shudder to think about what a waste of time this all was.

But none of us should be fooled. After Auschwitz something broke in the soul of American Judaism. All the old types were there, save for perhaps Yenta the Matchmaker. But the rabbi, the secular leadership, the law, prayer, community, peoplehood, even God (especially God) - everything needed to be redefined.

Perhaps Fred Neulander’s story netted six figures because we wanted to read about a rabbi who was a murderer. Perhaps it gave license to the ambivalence we were felling about it all - about religion, rabbis, God, and this people called the Jews that evertyone hates. Perhaps the rabbi represented all that we hate about ourselves. And after Auschwitz, perhaps we hated it more than ever before.

For those who are looking for some fascinating background material on the psychological underpinnings of the rabbi-congregant relationship, I highly recommend the essay by the late Richard Rubenstein, “A Rabbi Dies.”

No comments:

Post a Comment