From Greenland to Gaza to the Gulf - Teaching Trump About "Thou Shalt Not Covet"

The world is now subject to the whims of the world's most rapacious man, now completely unfettered, able to grab anything his heart desires. Perhaps a little lesson on the tenth commandment might help

After three weeks in office, it has become clear that, even more than his first term, President Trump’s decision-making process is guided by one thing above all - his insatiable urge to possess. “I want, therefore I am,” is his credo, and whereas Donald the child might have simply wanted a train set - or just not to get slapped in the face in military school - and Donald the playboy collected women and casinos, Donald the occupier of the Oval Office collects countries and large bodies of water with lots of bad weather.

He is the world’s most rapacious man. And let me throw in a few synonyms, because the word rapacious has multiple meanings that all apply here, including greedy, predatory and mercenary, as well as a four-letter derivative that sounds like rapacious that a number of women have accused him of (though I am not). You can see the synonyms here1.

Want Greenland? Me take Greenland. Want Gaza? Me take Gaza. Canada and Panama too. Jealous of France’s military parade? Me have what Macron’s having. Want access to everyone’s personal information? Take it. Want unfettered power to bypass Congress? Take that too. Ignore the courts? Sure, why not? Me take it all. Tomorrow belongs to me.

No one is stopping him. He takes and he takes and he takes.

Why does he want beachfront property in Gaza? Isn’t Palm Beach enough? Why Greenland? Aren’t the vast mineral riches of the US enough? Why Canada? Aren’t hockey players from Massachusetts and Minnesota enough?

And what is the big deal about the Gulf of Mexico? America? (Maybe just call it “The Gulf” and save the mapmakers a ton of money). Why take possession of a body of water best known for oil spills and horrific hurricanes? And changing the name changes absolutely nothing, except it screams to the world, “Me want! Me own! Me take!” When did our country’s sacred symbol transition from the bald eagle to Cookie Monster?

In the end, our president is nothing more than a toddler at an ice cream stand. If his first words weren’t “I want,” that’s because he was speaking to a father who would never give him what he really wanted anyway. All his “I wants” to his dad came down to “I want to be loved.” If only he had procured that love while a child, Greenlanders wouldn’t be forced to ponder a future under new management and Canadians wouldn’t have to bear the thought of having to matriculate in the US electoral college (I’m actually salivating over that possibility, but don’t tell Donald).

So from my profoundly simplistic perspective as a rabbi, I’ve come up with a solution to our problem. And yes, I am aware that The Golden Girls did come up with the solution of moving Gazans to Greenland decades ago.

That’s not the solution I’m looking for. My main question is not how to solve the Middle East (though I’ll get into that below), but how do we get Donald Trump to stop grabbing for things that don’t belong to him?

The answer…

Get him to read the Bible.

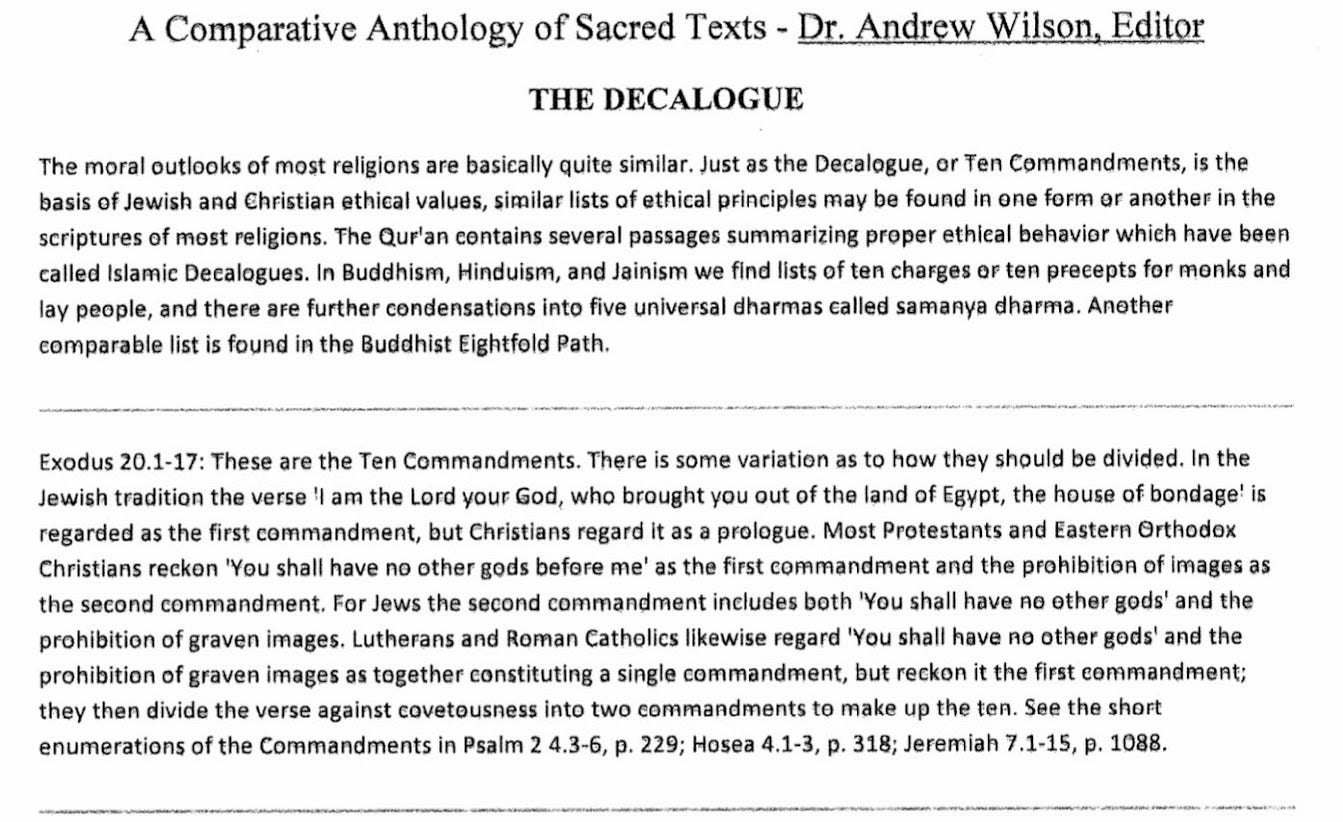

I’ve written about the Ten Commandments often in these pages, usually expressing my concern for their being fetishized by a Christian right wishing to obliterate that precious line separating church and state. But in this case, I want to focus on the commandments’ content, not their symbolism, and in particular the tenth, the one about not coveting. It so happens that Jews around the world will be reading the Big Ten this Shabbat as part of the Torah reading cycle.

Now Trump has made it clear that he wants to be a champion of religion, and the Bible in particular, which he has called his “favorite book,” even though he had trouble naming his favorite verse.

So let’s put that to the test. Maybe he never got as far as the tenth commandment. Maybe he got stuck on 7 and 8, about stealing and adultery, and never made it to coveting. After all, coveting seems so innocuous, the only one of the bunch that involves intent rather than action.

So for President Trump’s benefit, I’d like to give a quick primer here about the tenth commandment, why it is so important not to covet, why this commandment is so universal, how it ties into what is happening right now. And why you can’t claim the mantle of God’s Chosen if you are choosing the Panama Canal over God.

Seven things about the tenth commandment:

1. The tenth commandment teaches us to be satisfied with what we have and not always to want more.

“Who is it that is truly rich?” Benjamin Franklin once asked. “He who is content.” And who is that? Franklin asked. “No one.”

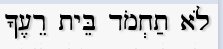

Samayach b’chelko (being content with your lot) is a prime Jewish value derived from this Talmudic passage from tractate Avot:

That whole passage is as brilliant as anything produced by the rabbis, both for how it rolls off the tongue with a dazzling instinct for literary turn-of-phrase (it was written to be memorized) and its ethical impact. If only Donald Trump had this chapter at his bedside during his first marriage rather than Hitler’s speeches, the nation would be in far less peril right now.

The psalm cited in this passage (128:2) states that the person who rejoices in fruit of their labors “shall be happy AND shall prosper.” Why the redundancy? The Talmud teaches that the verse refers to happiness and prosperity in both this world and the next. I’m no expert in the afterlife, but I can say that a significant number of the eulogies I write quote this passage. If someone was clearly satisfied by what they had while alive (including family, friends, and minimal possessions), that person will be recalled with deep fondness, reverence and love long after their death. And that, in Judaism, defines, at least in part, immortality.

Now Trump has made it clear that he wants to be a champion of religion, and the Bible in particular, which he has called his “favorite book,” even though he had trouble naming his favorite verse. So let’s put that to the test.

2. The tenth commandment teaches self-control

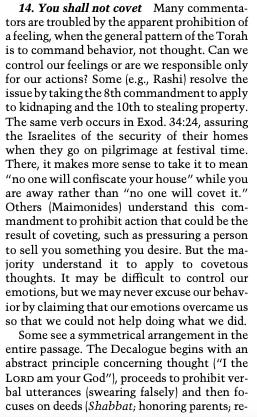

Coveting may itself be an emotion, but commentators emphasize that it is an emotion strong enough to lead to impulsive action. According to one Hasidic leader, the tenth commandment is less a prohibition than a promise, the natural result of following the other nine.2 If you don’t kill, lie or steal, and if you respect the Sabbath, your parents and God, you are very unlikely to succumb to jealously or rapaciousness. You’ll automatically fall into line, in good way.

3. The tenth commandment prohibits seizure of another person’s home - or homeland.

It says not to covet your neighbor’s house. The commentator Sforno uses a biblical reference to explain why,3 reminding the reader that the ancient Israelites had to make pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year, and that God promised them (Exodus 34:24) that “none of our neighbors will covet our land while we are engaged in” those journeys. God agreed to act as an ADT Home Security system for the tribes, but the best way to keep your home safe, God instructs, is not to covet theirs.

That lesson seems especially relevant these days, with homes and homelands perpetually under attack, and the President of the United States treating families with thousand-year ties to various homelands like pawns on a chessboard.

Just a word here about Gaza, a quick but needed excursus. I have made it clear in a previous piece that Trump’s plan for ethnic cleansing is appalling. Let me also be clear that under no circumstances should Hamas be allowed to represent the Palestinian people ever again. What they did on October 7 was in fact genocidal in intent - the goal being to kill all Jews. Genocide is still in their platform. It has never been in Israel’s.

For those seeking a clear understanding of some of the salient issues involved here, I highly recommend the new book, On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence and Justice, by Adam Kirsch. It’s short, clear and readable, brilliantly argued without being condescending. You can also see him on a number of videos and podcasts, including one below from the Hoover Institute. 4

For a Palestinian perspective (which also includes Kirsch’s rebuttal), I recommend this New Yorker podcast. If you don’t have time for Kirsch’s brief book, read Michael Walzer’a superb review, which summarizes the main points.

Kirsch speaks of the ideology of settler colonialism much in the way we think of the tenth commandment, emphasizing that key word “rapacity” as a craven coveting attributed to colonialism while offering a critique of contemporary theorists Sai Engler and Gerald Horne, stating (pp. 59-61):

What’s distinctive about settler colonialism as a tool of political analysis is that it sees all types of social injustice as flowing from a single source: the rapacity of European settlers…For the ideology of settler colonialism, the insatiable demand for more - more power, more land, more resources, even more knowledge - is not heroism, but rapacity, as when Horne refers to “rapacious colonialism” or Englert to “rapacious… settler hunger.” This rapacity is the nexus between colonialism and the "interlocking forms of oppression" it sponsors. And taking for granted that he should grab as much of the world as he can, the settler assumes that no one else has rights that need to be respected.

He goes on to demonstrate that an ideology that sees the world in this way can justify almost any form of retribution, up to and including October 7. When we are looking back to find the original deeds of ownership, ultimately no one really owns the house that we covet. And, as Kirsch explains, when it comes to Israel - Palestine, both peoples can lay legitimate claims to being indigenous, wronged and not colonizers.

And yes, rapacity seems to be the word of the day. Everything wrong in the world can be traced to those who take and they take and they take.

But peace will only appear in that tiny gap between what we want so badly and what we nonetheless won’t take, in spite of those overwhelming urges.

Peace won’t come until we covet it - peace itself - more than we covet our neighbor’s house. Peace might come when people stop debating names like West Bank vs. Judea and Samaria (reportedly next on Trump’s agenda) and instead call it both - or neither. I often go with a generic “the Territories,” (Shtachim - שטחים) as many Israelis have done over the years, or possibly the “Disputed Territories.”5

What’s in a name? Many Jews born in the pre-1948 period call themselves “Palestinians,” because they lived in what was called Palestine. The significance of names is temporal and fleeting, which is why God cannot be pinned down to a single, time-bound, knowable name. You can take that to the bank - the West Bank - and park it in the Gulf… of whatever. Maybe we change the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of Tonkin, just for fun. It is foolhardy to be so obsessed with ownership that you need to own not just the thing, but the name of the thing. But it’s the home itself, by whatever name, that should not be seized, rapaciously or otherwise.

And while we are talking about the seizure of homes, houses of worship are fighting back against the invasion of their sanctuaries - spiritual bastions of security for vulnerable parishioners. Just today more than two dozen Christian and Jewish denominations and associations sued to protect their houses of worship from rapacious attack. God, the ineffable, is fighting back.

4. The tenth commandment prohibits “grabbing them by the XXXXX” or even wanting to.

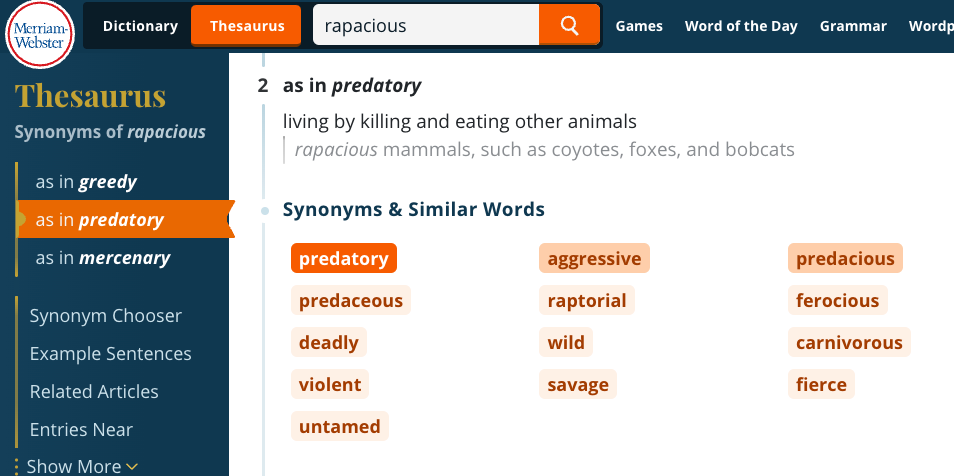

The medieval commentator Abraham Ibn Ezra spelled it out in a manner both medieval and quite contemporary, with an Oedipal hint of Freud.6 He writes:

The intelligent person will therefore neither desire nor covet. Once he knows that God has prohibited his neighbor’s wife (or his own mother) to him she will be more exalted in his eyes…. He will therefore be happy with his lot and will not allow his heart to covet and desire anything that is not his. For he knows that that which God did not want to give him, he cannot acquire by his own strength, thoughts, or schemes. He will therefore trust in his creator, that is, that his creator will sustain him and do what is right in His sight.

Ibn Ezra felt that even feelings as strong as lust are under our control. Others did not agree, saying that this commandment only spoke to acting on those feelings, not the lust, gluttony or greed themselves.

But in the end, our president is nothing more than a toddler at an ice cream stand. If his first words weren’t “I want,” that’s because he was speaking to a father who would never give him what he really wanted anyway. All his “I wants” to his dad came down to “I want to be loved.”

5. Coveting is far more fundamental than a simple struggle with materialism. It brings into question our trust in God.

This Christian perspective comes courtesy of Crosswalk.com:

Both the Old and New Testaments of the Bible regard coveting as a sin because it is an unhealthy desire for what others have, which can lead to further wrongdoing and is contrary to a life of contentment, gratitude, and trust in God…. Coveting, a sin inextricably tied to our want, is a corruption of what was created in us to be the mechanism that draws us to the Lord. Our want is the door through which we enter into satisfaction in God. Coveting turns our attention from our good Provider and fixates it on anything of lesser value. It leads us to believe that we can be satisfied in creation apart from the Creator.

It then plants seeds of distrust. We begin asking questions of the Lord. Is he really good if he hasn’t given me all I want? Does he really know what’s best for me?

In all of this, we are questioning truths fundamental to our salvation.

That message is also seen back in the Talmudic tractate Avot (4:21): Envy and desire and ambition drive a person out of the world.7

I saw the same message in several other Christian sources: The more you covet worldly goods, the more you risk losing the spiritual ones - including and especially God.

You don’t want to lose God, do you, Mr. President?

6. Every major religion condemns selfishness, lust and greed. Coveting is a no-no, all across the world, and for all time.

Take a look at The Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts (a treasure for any comparative religion nut like me). I’ve extracted the parts on coveting in the footnotes.8 It’s impressive how central this issue is to so many faiths.

Planning a trip to see your best bro Modi in India, Mr. President? Going to see Xi in China? No matter where you travel, you will be entering a “No Covet Zone.”

Here are a few examples from world religions:

There is no crime greater than having too many desires;

There is no disaster greater than not being content;

There is no misfortune greater than being covetous. Taoism. Tao Te Ching

What is that love which is based on greed?

When there is greed, the love is false. Sikhism. Adi Granth, Shalok, Farid, p. 1378

O my wealth-coveting and foolish soul, when will you succeed in emancipating yourself from the desire for wealth? Shame on my foolishness! I have been your toy! It is thus that one becomes a slave of others. No one born on earth did ever attain to the end of desire.... Without doubt, O Desire, your heart is as hard as adamant, since though affected by a hundred distresses, you do not break into pieces! I know you, O Desire, and all those things that are dear to you! The desire for wealth can never bring happiness. Hinduism. Mahabharata, Santi Parva 177

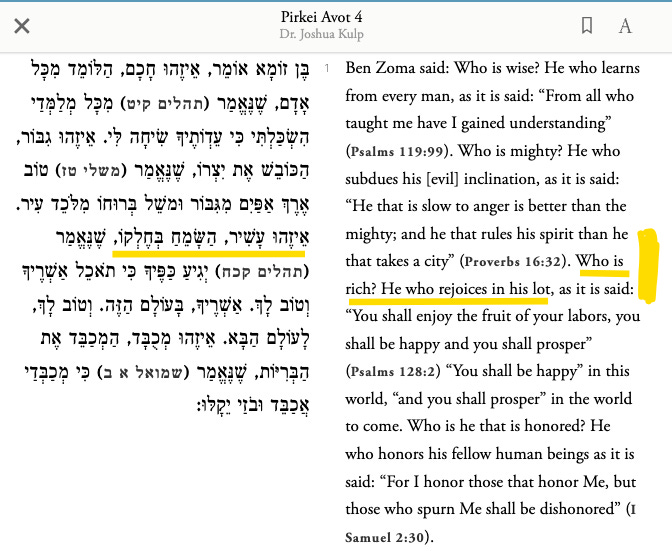

7. There are different ways to covet, and the commandment prohibits pressuring someone to sell you something they don’t want to sell.

The Ten Commandments appear twice in the Torah, and a different word for “covet” is used each time (the word lo, which appears in both versions, means “thou shalt not”). In Exodus it’s lo tachmod and in Deuteronomy, lo titaveh. Here’s how Jewish law differentiates between the two - one is more about action and the more about thought - and how rabbis codified which concrete acts fall under the rubric of lo tachmod (source: halachapedia). You can see how so much can be derived from a short Hebrew commandment, and how much it can mean for our lives - and our politics.

Read through these laws and think about Greenland, Gaza and the Gulf.

Ignore some of the sexist and parochial touches here and try to get at the essence of what it really means not to covet. (Incidentally, Poskim are rabbinic authorities who rule on case law).

And so, President Trump, anyone who really loves the Bible - and isn’t just lying about it before God - will certainly want to obey the tenth commandment! That means, quite clearly, not forcing Denmark to sell Greenland and not forcing Gazans into exile so you can develop beachfront property or steal a vineyard like King Ahab, or whatever it is you want to do. Just because you covet something, that is not license to act on it - to take and to take and to take.

I’m talking to you, Mr. President.

Mr. President?

Sforno: The object you covet should be considered by you as so utterly unattainable that you will not even begin to hatch schemes of how to acquire it. This is the promise made by God in Exodus 34:24 that none of our neighbors will covet our land while we are engaged in making the pilgrimages to Jerusalem. Once you begin to covet something belonging to someone else it is only a short step to committing robbery. (compare Joshua 7:21 where Achan ben Carmi who had become guilty of such robbery admitted that it all began with his coveting the items which he stole and hid.)

Here’s a transcript of a key section of that lecture (beginning at 45:20):

When Hamas fires rockets into Israel, that's also resisting settler colonialism because it's resisting a country that also does not deserve to exist and should not be there.

Some of the book, towards the end, I sort of try to get into the question of why. I think that's a bad framing for the Israel Palestine conflict. Now, I started writing this book after October 7 and wrote it in about six months. As you can see, it's a short book in order to sort of have this enter into the discussion as quickly as possible. And so that means that the war in Gaza was changing a lot while I wrote it. And I don't discuss the war in Gaza in any detailed way in the book. Obviously, the sort of emotional and political grievance or the sort of fuel of the anti-Israel protest is the death and suffering of people in Gaza.

So there's no ultimate way to defuse that sentiment or to fuse that kind of protest without some sort of peaceful resolution of the current conflict, and ideally over the long-term.

And that's something that I don't, and I don't know who does see as any kind of imminent prospect. So that is not something that I get into in the book. What I do get into in the book is the way that seeing this conflict through the lens of settler colonialism shapes the way that people think and talk about it. I'll give just one example.

One of the sort of shibboleths on the left in talking about the Israel Hamas war is that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. And by shibboleth, I mean, if you will not say that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza, you will not be allowed into any progressive spaces or increasingly into spaces like a book panel at a literary festival, where the other two writers on your panel say, I won't appear with a Zionist, by which they mean someone with a Jewish last name, which is something that has happened a lot. I'm in New York, this kind of thing happens every week.

There's a new example of this. Sometimes it's very ironic, you had an anti-Zionist Jewish writer trying to have a book event at a bookstore in Brooklyn. The manager of the store wouldn't let him in because he was a Zionist, by which he just meant that he was Jewish. Now, seeing the war in to say that what's happening in Gaza is not a genocide is, in a way a sort of disgraceful and obtuse thing to say, because it sounds like you're saying you haven't killed enough people yet for it to be a genocide, and that I don't care about the people who have died there.

And I understand that that's not a position that anyone wants to be associated with.

However, I think it's notable that, as I say in the book, I quote some people that on October 7, there were a lot of people who said this was justified resistance against a genocidal state. In other words, before there was a response, before there was an invasion of Gaza, the idea was Israel is a genocidal state, therefore, this is resistance to genocide.

And I think that if you look at the history of the Israeli Palestinian conflict, if you define genocide to mean the attempted destruction of people, that that is not an empirically tenable description of that conflict.

One way of thinking about it is if you think of the settlement of North America as an example of genocide.

In the 75 years after the pilgrims Puritans settled New England, the native American population is estimated to have fallen by about 90% in 75 years, mostly because of disease. If you look at Israel and Palestine, the Palestinian Arab population in that entire territory has gone. Has grown by about 500% in the last 75 years, from about 1.3 million to more than 7 million today.

In fact, between the river and the sea, to use the slogan that we all know, the Jewish and Arab populations are about equal, about 7 million each.

So clearly, there has not been an attempt to commit a genocide of Palestinian Arabs.

The one reason why that idea is so sort of instinctively plausible to many people is that settler colonialism is genocidal by definition. The discourse of settler colonialism is about genocide. There's a quote by Patrick Wolf to that effect as well, that when we talk about settler colonialism, we're talking about genocide. And you can see how, looking at the fate of aboriginal Australians or Native Americans, that that idea might be more plausible. Although I would say just as a sort of further complication, actual historians of Native America, I think, tend to resist the idea of settler colonialism because they know that, in fact, the story of that war between different peoples lasted over many centuries, and there were different moments at which different groups and entities had the upper hand.

It was not a genocide in the sense that the Nazi Holocaust was a genocide in which, in the space of four years, 6 million people were exterminated. That, of course, is the event for which the term genocide was invented.

But in the world of settler colonial studies, the term genocide has been sort of redefined.

Or the extension is the term has been extended so that a genocide is not only the physical annihilation of a group of people, it's the destruction of a people's culture and way of life. And so by that definition, as one person, I think, from the University of London, Damien Short, I think is his name, says it's not actually necessary for anyone to die for there to be a genocide, because a genocide is a structural process in which a people loses its way of life, its language, and its culture. So, for example, things that have been described as genocidal in this context are national parks, because a national park maintains the sovereignty of the settler society over indigenous land.

So a national park is an instrument of genocide, or even more particularly, mining is an instrument of genocide because it's about violating the land that the settler colonial society has occupied.

So when all of those ideas are in the air and the sort of equation of settler colonialism with genocide is almost intuitive and taken for granted, when a war does break out between Israel and Hamas, the idea that it's a genocide is very ready to hand and was adopted very quickly.

So to finish, and this is how the book finishes as well, I don't want to be and wouldn't want to be in the position of denying the injustices that are at the root of the idea of settler colonialism.

What I think is important to sort of look at and to think about is how do we respond to historical injustice, especially if we are legatees of it in some way, beneficiaries of it in some way.

There are numerous arguments that could be made and that I have heard people make and sometimes gotten into myself. One is that this is a discourse that looks exclusively at the history of English speaking countries founded by European colonists, plus Israel, and not the entire rest of world history. Which is mostly the case, although there are some people in settler colonial studies who do, and we'll say, for example, the Japanese occupation of Manchuria was settler colonialism.

But the idea that you might look at the history of the world and say, well, why do people from North Africa into Central Asia practice Islam? That's because of settler colonialism. Why is Russia the biggest country in the world? That's because of settler colonialism. In essence, the entire history of the world is the history of conquest and settlement and cultural destruction and change and imposition.

So to single out these particular countries for study, at the very least, is ahistorical. And to single out Israel in particular, as the one country in the world today where there is an active conflict against settler colonialism, where a country deserves to be destroyed, I think is unjust. It's an injustice.

It also leads to certain ways of thinking and talking that I think are very parallel to classic anti-Semitism and anti-Judaism.

You would not believe how many disputed territories there are in the world. Click here and start counting. It will take a while.

See Ibn Ezra’s complete commentary on that part of the verse below:

THOU SHALT NOT COVET. Many people are amazed at this commandment. They ask, how is it possible for a person not to covet in his heart all beautiful things that appear desirable to him? I will now give you a parable. *Which will aid you in understanding the commandment that prohibits coveting. Note, a peasant of sound mind who sees a beautiful princess will not entertain any covetous thoughts about sleeping with her, for he knows that this is an impossibility. This peasant will not think like the insane who desire to sprout wings and fly to the sky, for it is impossible to do so. Now just as a man does not desire to sleep with his mother, although she be beautiful, because he has been trained from his childhood to know that she is prohibited to him, so must every intelligent person know that a person does not acquire a beautiful woman or money because of his intelligence or wisdom, but only in accordance with what God has apportioned to him. Indeed, Koheleth states, yet to a man that hath not labored therein shall he leave it for his portion (Eccles. 2:21). Furthermore, our sages taught, children, life, and sustenance are not dependent upon a person’s merits but upon the stars. *Mo’ed Katan 28a. The intelligent person will therefore neither desire nor covet. Once he knows that God has prohibited his neighbor’s wife to him, she will be more exalted in his eyes than the princess is in the eyes of the peasant. He will therefore be happy with his lot and will not allow his heart to covet and desire anything which is not his. For he knows that that which God did not want to give him, he cannot acquire by his own strength, thoughts, or schemes. He will therefore trust in his creator, that is, that his creator will sustain him and do what is right in His sight.

Commentary on Avot by Joshua Kulp: Rabbi Elazar Ha-kappar said: envy, lust and [the desire for] honor put a person out of the world. This saying is parallel to the saying of Rabbi Joshua which we saw in mishnah 2:11, “Rabbi Joshua said: an evil eye, the evil inclination, and hatred for humankind put a person out of the world.” It may even be that Rabbi Elazar is interpreting Rabbi Joshua’s statement. An evil eye causes a person to be envious, lustfulness comes from the evil inclination and hatred for humankind stems from an overwhelming desire to rise above everyone else, hence a pursuit of honor. These things “put a man out of the world”, meaning they interfere with his ability to function in this world and they cause him to lose entrance into the world to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment