In This Moment

Shabbat-O-Gram, Oct 23, 2020

TBE Hebrew School in 2020: The New Normal

Mazal tov to Camryn Laichtman, who becomes Bat Mitzvah this Shabbat morning

Shabbat Shalom!

As we fight off the next wave of the virus - and Stamford is now classified as a "yellow" zone - a shout-out to all those who are fighting off virus fatigue, which is natural to feel after all these months. If we remain vigilant, we will save lives.

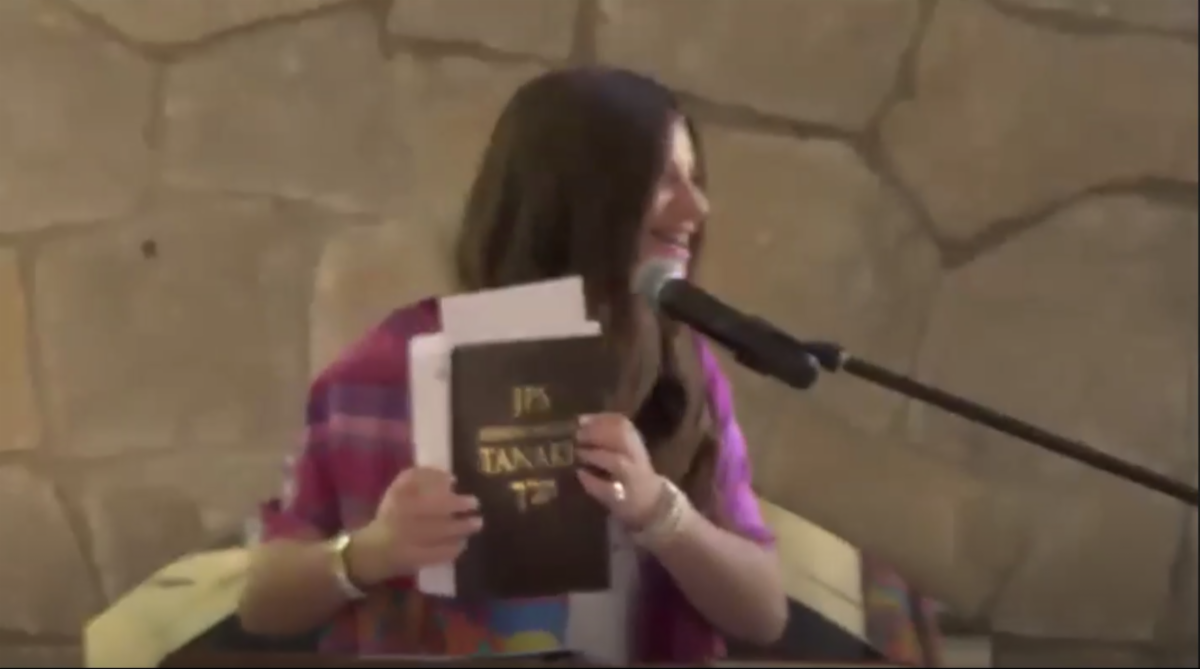

Meanwhile, undaunted, we forge ahead. Mazal tov to Camryn Laichtman, whose bat mitzvah takes place this Shabbat. Sydney Kassel, last week's week's bat mitzvah, did us proud (as they all do!). You can see some photos, video and the text of her d'var Torah here. Below are some screen grabs from the service. Notice how we magically transported to her home her kiddush cup and Tanakh through the space-time continuum - without benefit of a DeLorean!

Some required reading:

The Covid-19 pandemic will be outlasted by the grief pandemic - and no one is preparing for it - an important article co-written by TBE's own Gabi Birkner (of "Modern Loss" fame)

An Urgent Call to Action - Sign the Petition Here

A Blessing for Fall Foliage

In this week's portion of Noah we read of the sign of the rainbow, which was given by God as a promise never to destroy the earth again.

The Bible believes that all natural events are invested with divine portent. The rainbow isn't the only natural phenomenon that is given some sacred meaning. Think of thunder, earthquakes, eclipses and, in this portion, floods. All of these are controlled by God and serve some historical or morally instructive purpose. They are signs of God's rulership over the natural order. The ancients gave the rainbow its name - in Hebrew it is simply a bow - because they considered it to be God's bow of war, but the Torah transformed it into a symbol of peace.

While we may no longer directly connect it to God, the sense of peace that we feel when we see a rainbow is analogous to how our ancestors must have felt. The storm is over, the threat is gone, and there will be no more great floods. How beautiful it must have appeared - and how beautiful it remains.

What prompted all of this contemplation on my part were a couple of drives that I made recently to enjoy the foliage of fall in New England. So much has been taken from us this year, but I wouldn't let Covid take autumn away too. So, with the Jewish holidays mercifully over by Columbus (Indigenous Peoples) Day this year, I spent a couple of free days driving around New England. I spent a full day in Litchfield County, checking out places like the old bridge at Lovers Leap Park, with its heartbreaking story of star-crossed lovers, a morality tale for our times.

And as I checked out the spectacular, changing trees, New England's gift to the world, I wondered, Is there a blessing for foliage? As we learn from "Fiddler on the Roof," there is a blessing for everything - except this. There's a blessing when witnessing flowering fruit trees in the spring. There's a blessing upon smelling fragrant shrubs, herbs and fruit. There is a blessing upon seeing things of striking beauty. But there is no specific blessing for fall foliage.

The great columnist Russell Baker called October the one month "where man and nature are most nearly in harmony." But Judaism knows nothing from October, And the Hebrew month we are now in is noted for Its lack of holidays. It's called Marheshvan, "bitter Heshvan" for precisely that reason.

The reason why there is no blessing for fall foliage is quite simple: our ancestors never witnessed it. Israel gets some color in the spring when the desert flowers bloom, but Israel's spring is noted more for its wonderful fresh smells than its appearance. And they don't have anything approaching what we call fall. I would assume that Babylonia's autumns are nothing to write home about either, which is why the Talmud is silent about the type of miracles nature has blessed us with this month.

If we were to compose a new blessing for fall foliage, it would need to emphasize how all of God's creations are unique and capable of producing exquisite beauty. For months upon months the trees are barely distinguishable, each producing leaves of similar color and texture. Then suddenly, like Cinderella at the ball, each tree explodes in color, producing a collage that no other can duplicate, and then each bears its branches and goes to sleep for the winter at its own pace, not feeling any particular need to keep pace with the others.

People are like trees. We all possess the capacity for spectacular beauty. Rarely are we inclined to let these possibilities float to the surface we prefer to remain safely embedded in the crowd, protected by the masses. But each of us has his or her day, and like the tree, each of us knows when that day is at hand. When our time comes to take that leap into the unknown, alone, we summon up the strength to do so.

Trees also teach us about the nature of glory. It is fleeting and yet it is real. For half a year trees build up to this blazing show, growing leaves, biding their time, swaying to and fro, as if rehearsing for this one moment. And when that moment finally arrives, after all the anticipation and fanfare, it is over in a matter of a few days. One wonders whether it is all worth it. Or is it all just vanity of vanities, the fruitless striving to achieve immortality?

It is worth it. What would our lives be like without the fall? Where would we be without the trees? As fleeting as the show may be, it is equally spectacular, and the memories of fall live on long after the last leaves have been raked. The glory may be momentary, but the beauty lives on, through memory.

There is a lot we can learn from the spectacular colors of the trees; they are for us what the rainbow was for Noah.

So here is my prayer for the foliage:

Blessed are You O Lord our God who gives each of Your creations the potential for individual greatness and momentary glory, and the capacity to record that glorious moment in memory as a permanent inspiration. Blessed are You, God, Who enriches our lives with spectacular color.

AJC Survey of American Jews

The American Jewish Committee's annual survey of American Jewish Opinion sheds light on the perspectives of American Jews regarding election-related issues, including the most important topics in their voting preference, which candidate would do a better job on key issues facing the U.S., and their choice in candidate. See the JTA's write-up of the report, the AJC press release, and an analysis of the findings. Beyond the pure presidential politics, if you read the AJC analysis, one thing that is clear is that there is an ever widening gap between Orthodox and non-Orthodox American Jews and between American Jews and Israelis - and a decline in concern for Israel among American Jews.

For comparison to prior years, see past AJC surveys of American Jewish opinion: 2019, 2018, 2017, and 2016.

Here is the current survey:

My blog post from the Times of Israel:

In the wake of President Trump's refusal to disavow white supremacy at last month's first presidential debate, the Jewish Democratic Council released a powerful 30 second ad making the direct comparison between Trump's tactics and the rise of fascism in 1930s Germany. Many cried foul, including the Anti-Defamation League, though prominent Jews like historian Deborah Lipstadt and former ADL director Abe Foxman sympathized with the ad's message.

So the question that has hovered over political debates and cocktail party conversations for decades once again came to the fore: Is it ever appropriate to use Holocaust analogies, and if so, when?

Yes it is appropriate, when done judiciously and respectfully and when necessary.

In my house, back when my kids were growing up, we had the Anne Frank Rule.

One night during a school vacation, my family was engaged in a stimulating round of "Apples to Apples" - that popular game where a rotating judge picks a descriptive card (like "refreshing," or "feh!") and other contestants select cards that they hope the judge will consider the best possible match (like "Passover" and "Alan Dershowitz"). Naturally, we were playing the Jewish version.

This particular game was one of our all-timers. It came down to the final hand, with my two sons and me each having a chance to win. With the game on the line, we doubled the stakes and pulled out two descriptive cards: "odd" and "offensive."

My sons played "Crown Heights," "my bedroom," "J-Date" and "Dennis Prager." I suppose any of those could have been the best match. But I held the trump card in my hand. You see, I had just drawn "Anne Frank." We have a little rule in my family, one suggested to us by a close friend. Whoever plays the "Anne Frank" card automatically wins that hand. No questions asked. The idea is that it would be offensive to Anne's memory, and by extension, all Holocaust victims, for Anne to lose to, say, "Joan Rivers" or "potato kugel."

But here, the exact opposite would be occurring. Anne would win for matching "odd" and "offensive." How could we shame her in this way?

I succumbed to that logic and pulled back the card. I lost the battle but won the war, as my family then engaged in a dialogue about how, just as Anne's is no normal card, the Holocaust is not just any old piece of the Jewish identity puzzle.

The "Anne Frank Rule" applies to our culture writ large just as it works for "Apples to Apples." Once the Holocaust is invoked in an argument, it usually is game, set and match-but only when the subject is raised at the proper time and by the proper person, and only if it is not overused. The Holocaust has been brought into so many political arguments, on all sides of the spectrum, that a new rule was created: Godwin's Law, stating that if a discussion continues long enough, inevitably someone or something will be compared to Hitler, which ends the discussion.

The Shoah offers numerous potential lessons that can be applied to contemporary situations, but it's debatable as to which analogies "work." Comparing any concession in international negotiations to the appeasement at Munich, for instance, is a tactic that has been so overused that its potency has been drained. Google "Netanyahu" and "Munich," for instance, and you get over 1,080.000 results. And President Trump was totally out of line when he recently compared New York City's crackdown on Orthodox Jewish anti-lockdown demonstrations to Nazi-era roundups.

So the Holocaust card, like the Anne Frank card, must be played sparingly and with due deliberation.

But in the Trump era, all bets are off.

When the Holocaust-related term "Concentration Camps" was used in July of 2019, in describing the crowded and squalid detention facilities used by the Trump administration for asylum seekers and other refugees at the U.S.-Mexican border, the U.S. Holocaust Museum cried foul. I winced a bit myself. But in an essay for Slate, Yale historian Timothy Snyder explained how and when Holocaust analogies are not only appropriate, they are necessary.

"To forbid analogies makes the Holocaust irrelevant to future generations. If an American child can identify with Anne Frank, an American child might ask what it is like for immigrant children to be separated from their parents. To forbid analogies is to forbid learning, and to forbid empathizing . . . The point of historical comparisons is not to seek a perfect match- which can never be found-but to learn how to look out for warning signs."

Even Michael Godwin, the originator of Godwin's Law tweeted after Charlottesville that his law had met its match in the Trump era. "By all means, compare these (expletive)-heads to the Nazis," he wrote. "Again and again. I'm with you."

The use of the Shoah in conversations about refugees or hate groups is completely appropriate, especially in light of the hundreds of thousands of Jews who were turned away at the door to freedom, including-it must be noted-the family of Anne Frank, whose father Otto sought to bring his family to America. Had she survived, Anne Frank would have turned 90 last year-and she could have lived a perfectly uneventful, happy life.

Holocaust analogies should be used sparingly, to be sure, but when used appropriately, there is no question as to who has the moral authority to play that card. Jews do.

I've never been a big fan of calling the Jews a "chosen people." Still, I never saw the concept as a signal of superiority, but rather as a summons and a responsibility, to bring Sinai's vision of holiness, justice and love to the world. Chosenness still calls on us to strive to repair the world, as it did at Sinai; but now our moral voice has been amplified 10 times over by historical experience. When Jews invoke Auschwitz, the world listens - because we were there. Many hate us for that, especially if they idealize fascism. Others admire us. But everyone listens.

We need to hold the Anne Frank card close to our vest, play it when necessary, and appreciate the moral power of its message.

And that message has never been more relevant than right now.

Shabbat Shalom.

Rabbi Joshua Hammerman

No comments:

Post a Comment