Before I begin, since this posting speaks to the topic of human beings playing God, it bears mentioning that the most extreme example of that kind of hubris is the kind of regime change that is happening now in Venezuela. To be clear, whatever you think of Venezuela or its abducted leader (spoiler - he’s bad), regime change ALMOST ALWAYS FAILS (and it’s not exactly a small sampling).1 I’ve dealt with this topic at other times (most recently recalling Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982).2 To be continued…

Let’s start this Waymo piece with this breathtaking view of San Francisco and the Golden Gate, a sacred intersection of natural beauty and human ingenuity.

On a recent trip to San Francisco, my son Ethan, who lives there, prevailed upon me and my wife to take a ride in a Waymo, those driverless cars that are all the rage, soon to appear in a city near you, which represent the next wave of A.I.’s takeover (if you are a skeptic) or salvation (if you’re a true believer). They are the latest examples of how technology can simultaneously appear sublime and specious, revealing both a hint of our Godlike power while exposing our limitations and ultimate powerlessness.

I’m going to share my impressions of the Waymo experience with you, but first, some personal background:

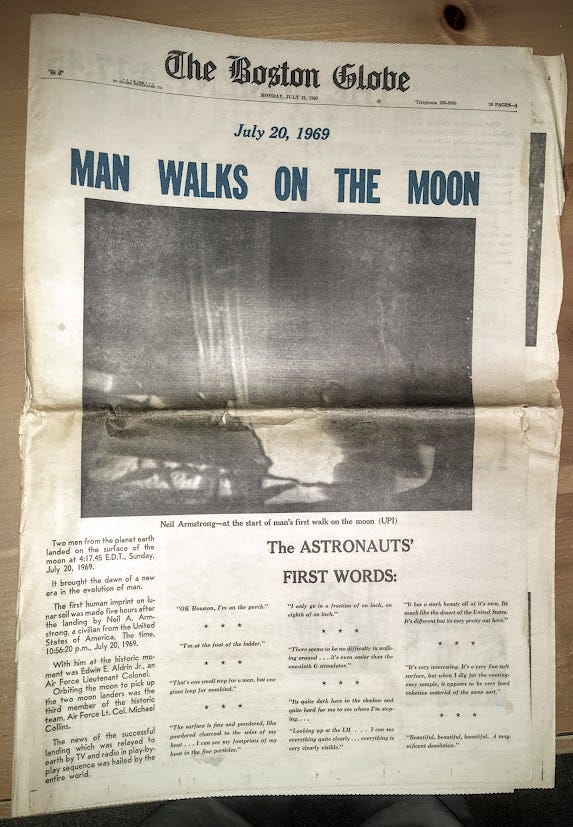

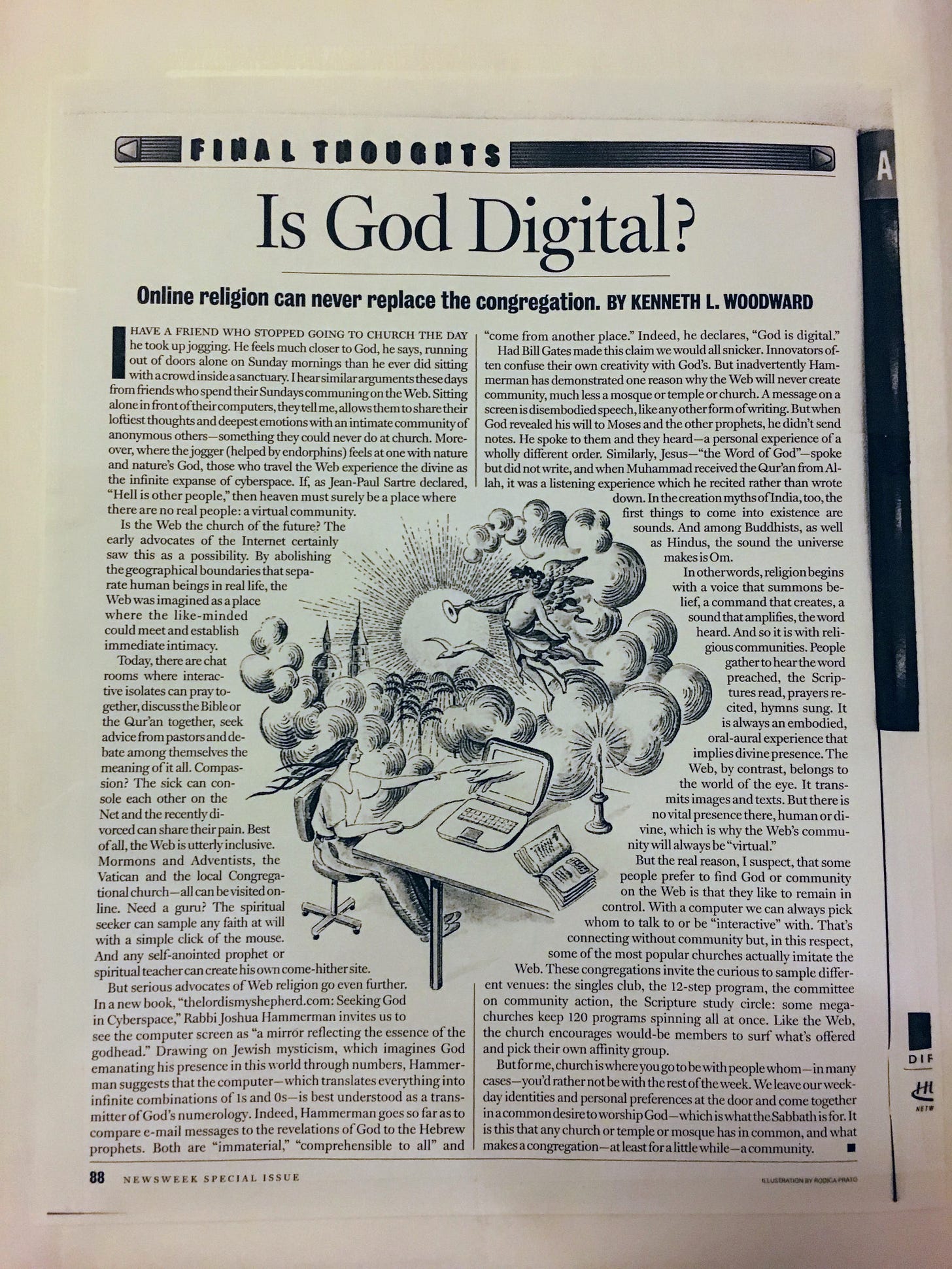

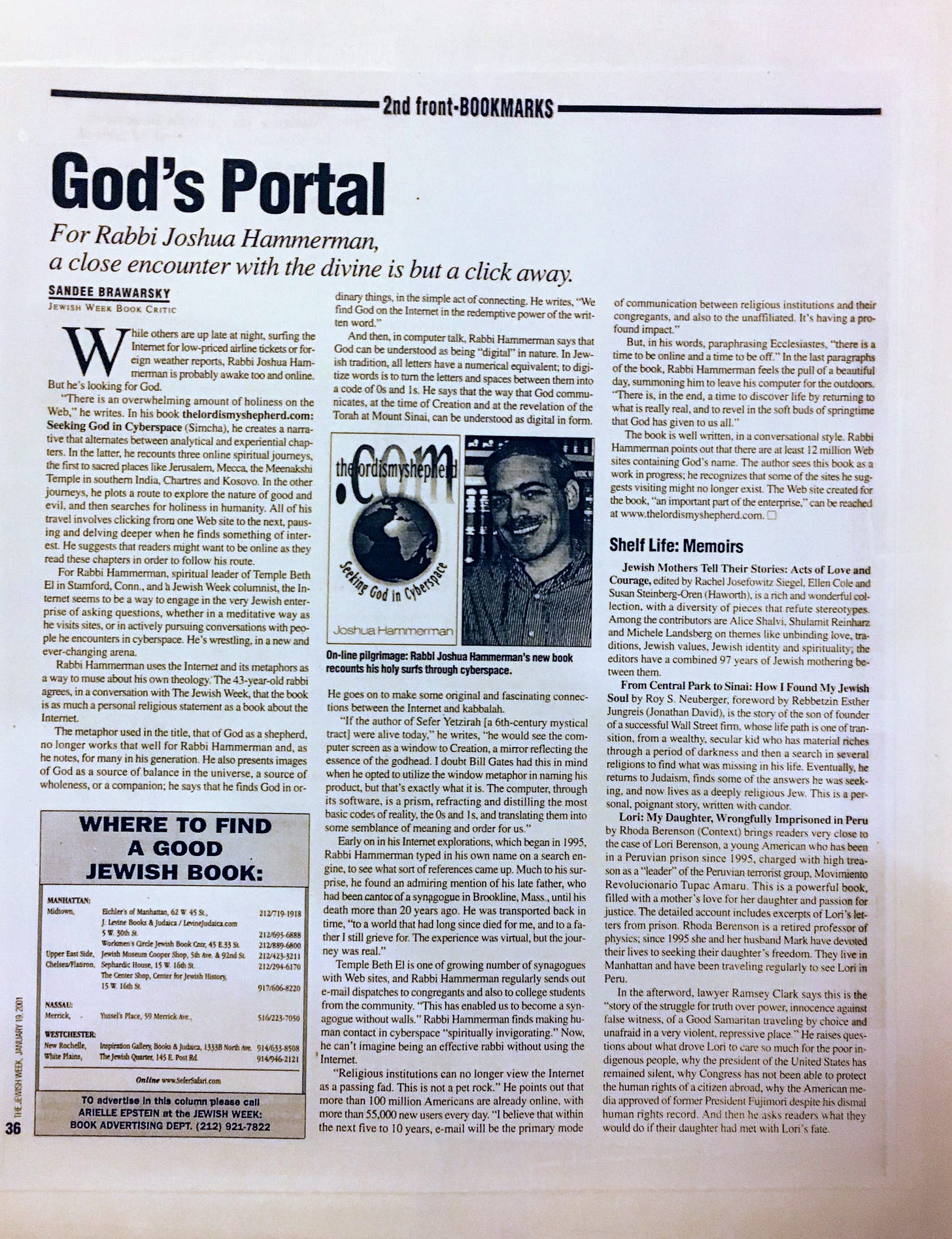

I’ve oscillated between skeptic and enthusiast when it comes to technological breakthroughs, but mostly I’ve gravitated toward the latter. I loved the moon landing as a child3, and swooned over the internet. In 2000 (now a quarter century ago) I wrote a book about finding God online, called thelordismyshepherd.com: Seeking God in Cyberspace, in which I boldly - or naively - declared that “God is digital.” To read excerpts from that book, click HERE and HERE4.

Here’s what I wrote in the book’s introduction:

I’ve found sanctity online. I've also found God in my VCR instruction manual. And in my home videos, my cell phone, my beeper, my remote control, my cable box and television screen. I've encountered God in the Hubbell telescope and the space shuttle, in my microwave oven and in a cloned sheep called Dolly. How I see God in these other technological phenomena is the subject for a more broad-based book; yet in some sense, a deep search for God on the Internet, the subject of this study, is a microcosm of the larger issue. And it is necessary to spend some time dealing with the general question of God and technology before we enter sacred cyberspace. Through my search for God on-line, I've discovered danger signals along the journey. God can be found on the internet, but God can also be lost there.

But when compared to prior innovations like the internet, artificial intelligence is a different “animal” entirely. A.I. is built on a premise that what appears artificial can approach, if not surpass, what is human, that a mechanical construct can fool us into believing that it is sentient; that it can learn from its mistakes, absorbing the wisdom of its - and all our - collective experience.

The wisdom of the hive has become a hot topic lately with the series Pluribus, the highest rated in the history of Apple TV, which describes the takeover of humanity by just such a collective mind, transmitted through DNA coding from another planet, which becomes a fountain of bliss for nearly the entire population of the planet. But happiness comes at the cost of our autonomy and individuality. It can be contended that A.I. leads us in that direction, and so does religion, which at times calls upon us to cede personal autonomy and trust only the Supreme Being, to metaphorically place God behind the wheel.

I feel fortunate that in the case of Judaism, even the choice to cede some autonomy must be a reasoned and autonomous choice, a covenant entered into - and continually reaffirmed - voluntarily.

And religion has a major role to play in making sure that we don’t make a god out of the works of our hands.

Especially now, when groupthink is so rampant, we must stand up for the primacy of personhood.

That said, as long as we recognize the dangers and limitations of thinks like the internet and A.I., technology can indeed improve the quality of our lives, and even save lives, and as such, it can be embraced.

In fact, when I explored Jewish views on technology for my book about the internet, I found that among rabbis through the ages, even the staunchest traditionalists understood that God gifted us powers of reason so that we would use them. They understood that when the first humans were instructed in Genesis to assert dominance over God’s creation, the Bible greenlit technological innovation.

Rabbi Avraham Ya’akov of Sadigora said this in the 19th century, an age that witnessed an exponential rate of innovation that rivaled our own:

“You can learn something from everything:

From the railway – we learn that one moment’s delay can throw everything off schedule.

From the telegraph we learn that every word counts.

And from the telephone we learn that what we say Here is heard There.”

It’s interesting that the modern Hebrew word “artificial” (Melachuti) comes from the biblical word “Melacha,” which means “creative work,” the kind of work done by God in fashioning the universe, the type of work that God ceased on Shabbat.

It’s noteworthy that the work done by humans in building God’s sanctuary, as described in Exodus, is also called Melacha. Melacha is godlike work, but when people engaged in it in construction the sanctuary, they were not actually creating a cosmos, but an artificial facsimile of it, the shadow of a cosmos, the Genesis Creation in miniature. 5

There’s nothing wrong with imitating the divine, as long as neither we humans nor our creations - including our collective wisdom - are elevated to divine status, and as long as we do not confuse what is man-made from what is not.

Sitting in the backseat of a driverless car was an ineffable experience for me, not dissimilar from how I felt the first time I went online.6 But it was also a reminder of the dangers of turning this magical chariot into a golden calf.

Riding the Waymo

I was nervous getting into the car but had trust, not in the technology, nor in God’s plan for me, but in my son, who had been in these driverless cabs a number of times. Still, as we prepared to embark on my maiden Waymo voyage from our restaurant to our hotel through heavy traffic, all I could think of was the scene from the comedy “Foul Play,” (one filled with racial stereotypes that would not pass muster these days), in which Japanese tourists find themselves in the midst of a high-speed car chase through those very same streets.7

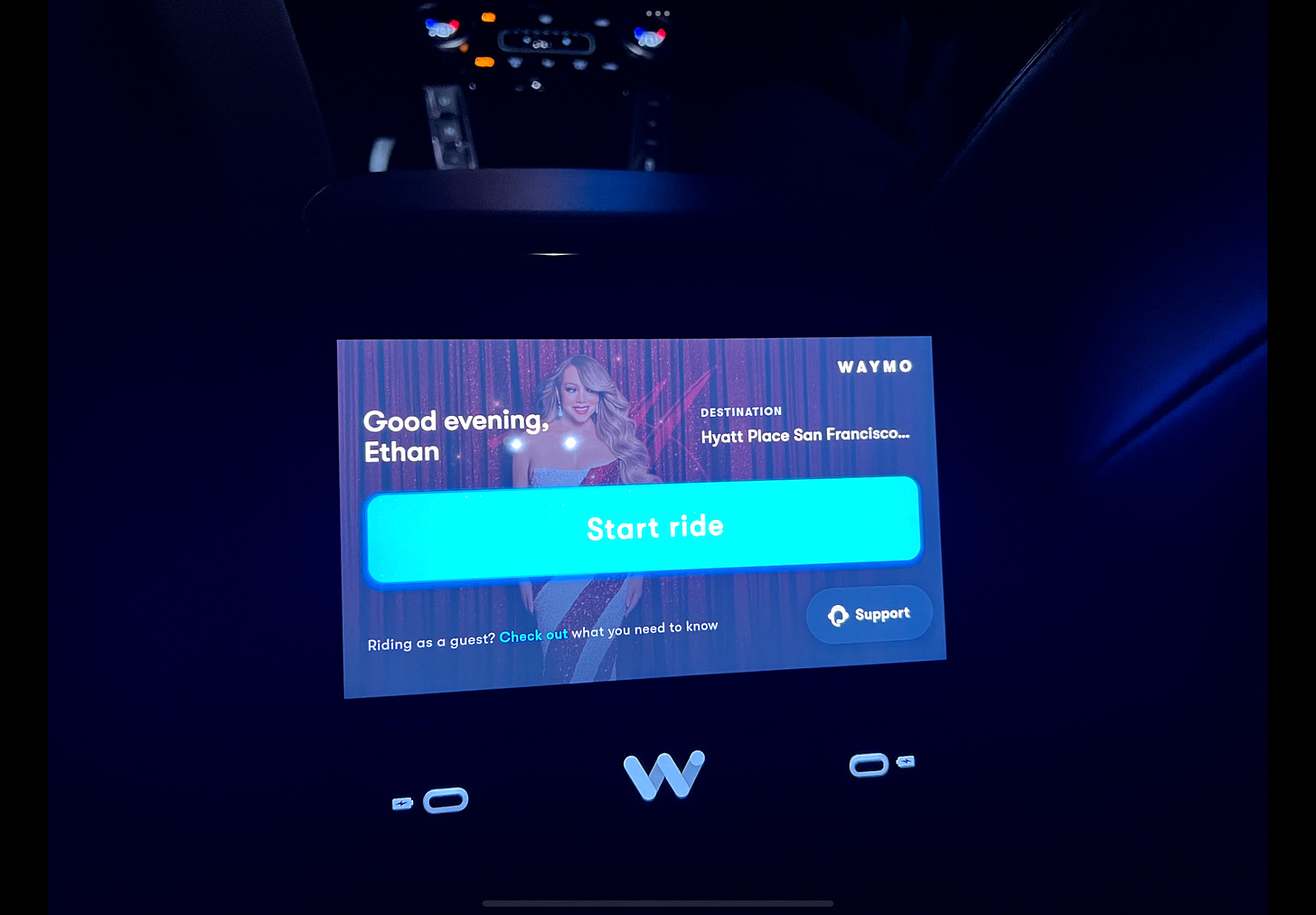

The car waited on a safe corner for my son, who had booked the trip through his account and the Waymo app.

His initials were illumined on the car’s roof and his first name appeared on the dashboard screen. All he had to do was push the Start Trip button - cheerfully anthropomorphized by an image of Mariah Carey, to begin the trip.

It started to drive and immediately began playing music from Ethan’s Spotify playlist - but then it abruptly stopped when Ethan asked it to.

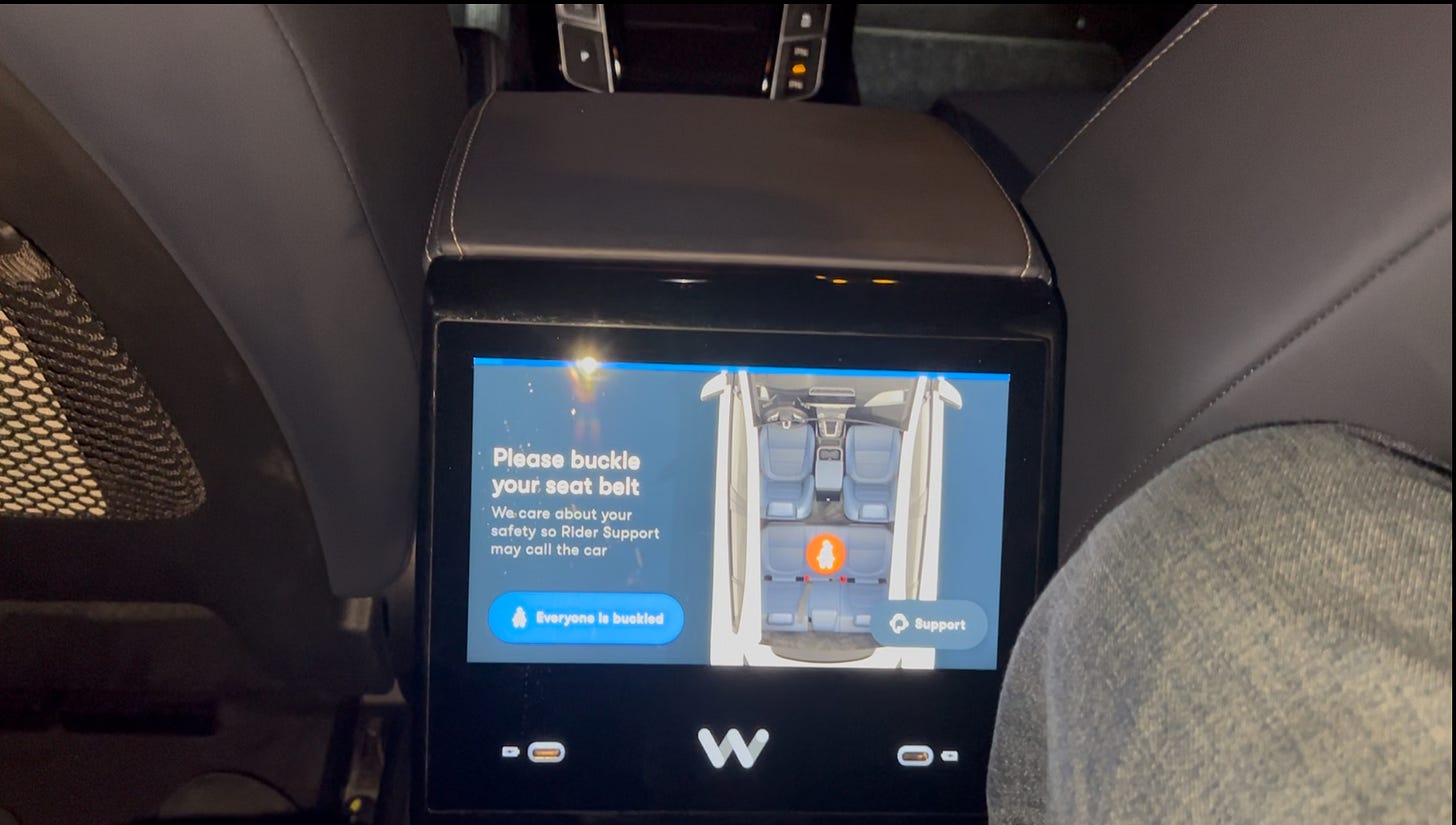

And the Waymo came to a halt and wouldn’t continue driving until I was asked to buckle my seat belt. If a human driver pulled over like this it might have ruffled some feathers among the passengers. But in the Waymo I obediently followed directions, knowing that there would be no room for negotiation.

I had to buckle my seatbelt or the trip would not proceed.

Once that was done, we were on our way. Here you can watch the Waymo’s expertly accomplished left turn:

Here it is, taking a right.

And here it is backing up - yes, backing up - to avoid being caught in the middle of an intersection after the light turned red.

Inadvertently we programmed it to take us to the wrong Hyatt, which we only noticed when the trip was nearly complete. Ethan opened the app and plugged in the new address and the Waymo changed course immediately, without sacrificing safety by attempting to lurch over two lanes or, heaven forbid, attempt a U-turn on Market St. No complaints from the “driver,” but the price instantly went up.

At one point, a human-driven car was parked illegally right in front of us in the left lane, so the Waymo had to shift over to the center lane, where heavy traffic was moving along fairly briskly and no one was letting us in. So it waited patiently, and when there was a small opening, it leapt (another awkward anthropomorphism) at the opportunity. I didn’t capture that move on my phone because, frankly, my eyes were closed.

Waymo cars are guided by an integrated radar-based system, with sensors and cameras both inside and on top of the car, which gives it always a clear, sharp 360-degree view, something no human ever has when behind the wheel. Plus, it has millions of miles of collective experience (and according to the company, billions in simulation) to fall back on. It sees everything with ultra-clarity: traffic, pedestrians, signals, road conditions, and, I must add, mischief-makers in the back seat trying to test it, make out or vandalize.

What it couldn’t see was a beloved cat named Tik Tok a few weeks ago, who was unfortunately killed by a wayward Waymo.

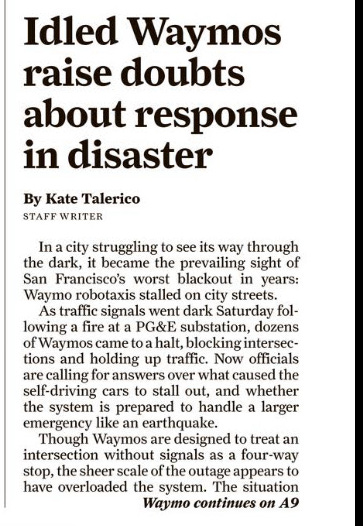

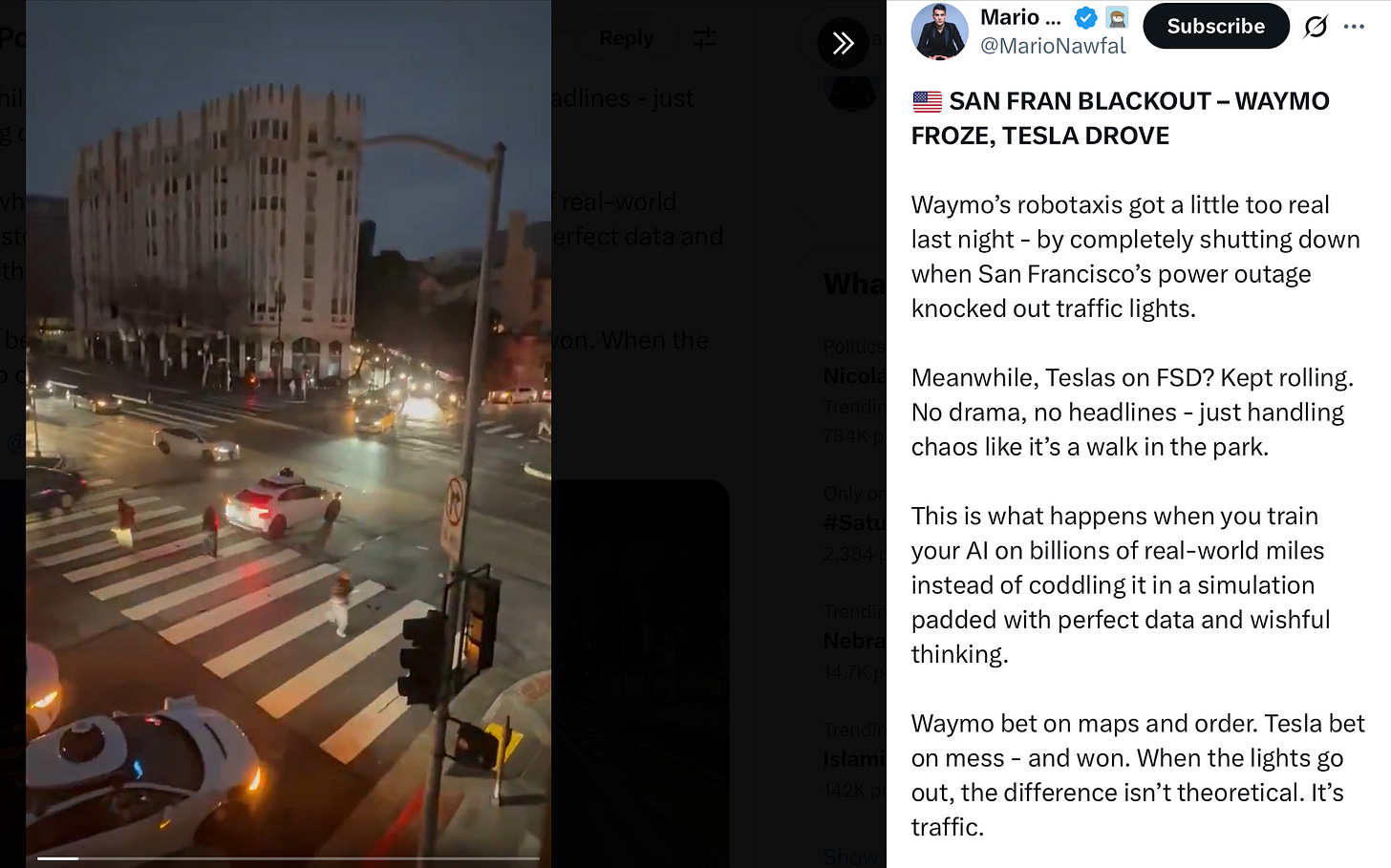

It also couldn’t see this coming: the massive power failure that hit San Francisco just before Christmas, which turned out to be its Kryptonite. While cars with human drivers managed to escape the ensuing mayhem, Waymos were left powerless and paralyzed by this sudden outage, a reminder of what would happen to the whole country if the Russians or Chinese were ever to shut down our power grids.

The montage of sleeping Jaguars on the streets of San Francisco was as jarring as those stalled elevators in Manhattan during the northeast blackouts of ‘65, ‘77 and ‘03.

Blackouts are always humbling moments that remind us of the limitations of our power - literally and metaphorically - and in the case of San Francisco’s, at a time when we are so tempted to place hubris, rather than a human, behind the wheel, we need to place our faith in a Higher Power.

We are not in control of our destiny.

But while we must continually remind ourselves that our power in not infinite, neither is it infinitesimal. For in our hands lies the power of life and death, of good and of evil, of severity and compassion. Who shall live and who shall die – the power is in our hands. We can topple dictators, and we can build a car that can drive better than individual people can, without sacrificing our cats.

Alphabet, which owns Waymo, has declared that they’ve solved the power outage problem, as was to be expected. Of course this hive-like creation would learn and improve from this collective experience. So things will be much better the next time there is a massive blackout. Mazal tov. But what happens when there is a directed attack just on these driverless cars, right after America has fallen in love with them?

There is also a human element that was definitively missing on my Waymo ride: Sure we were free to talk about anything without fear of embarrassment (though it’s safe to say every move was on camera). But it was so strange to not have any feedback from the driver.

Can a Waymo complain about the cost of toilet paper, or talk about its missing family back in Ukraine, or why it thinks Pelosi or Trump or Ronald Reagan is bad for America? Can it complain about the Knicks or show you a secret shortcut that avoids the Van Wyck and lands you at the best pizza place in Queens (Amore, if you really want to know - I learned that from Joe Gelb, of blessed memory, who used to drive me to JFK all the time)?

Sure we don’t have to tip the Waymo, but maybe we want to tip because it feels good to thank a human. And it sort of feels good to know that your driver cares about not getting a ticket, even if it means sliding through that yellow light that never seems to be synchronized with the next one. And it sort of feels good to know that your driver, whether due to empathy or self-preservation, wants you to be safe. A human driver, unlike the Waymo, has a stake in my survival - even if the Waymo appears, at first, to be more proficient at getting us from here to there, and has a billion miles more experience in doing so.

And what of all those drivers who will soon be out of work, just so I can enjoy my driverless jaunt? Is this joyride truly a producer of joy? Is replacing people really the recipe for happiness? Am I happier pumping my own gas than people were back when service stations really meant service, when the Texaco guys came rushing to check the oil?

Which one is better? Back to the Future, circa 1955?

Or the sterile, unpeopled pile of metal the movie’s sequel imagined a service station would look like in 2015?

A.I. is built on a premise that artificiality can appear real, that a mechanical construct can fool us into believing that it is sentient. It can even save lives (unless you are Tik Tok the cat).

But as we learned when the lights went out in San Francisco, even when A.I. learns from its mistakes and spews out more irrelevant fun-facts, it is still artificial, like the Bible’s sanctuary in the wilderness, which brought us a little closer to God and summoned sanctity into our world; but the minute the people thought they were in the divine driver’s seat they built themselves a golden calf, and God provided a ready reminder of who is really behind the wheel.

Technological innovation is inherently neutral. It can be good if it enhances what is real, what is human and what is truly alive, and it can be bad if it doesn’t. Technology can be a window into sublimity. But A.I. is also one of the greatest threats to our civilization 8

In the end, we must stand up for the primacy of the individual, rational, sentient, imperfect, human, human being. For, as Joe Gelb showed me a hundred times while getting off the Van Wyck at Linden Blvd to save us twenty minutes, enough time for a heavenly slice at Amores, that is what makes life worth living.

And now for something completely different….

Jewish Perspectives on the Messiah

Here’s a complete recording of a Zoom seminar I led for the leadership of the New England Lutheran Synod in December, as part of their Advent preparations. During the presentation, I discuss a packet on Jewish messianism that you can access here or download below.

Since the end of WW2, “the U.S. expanded the geographic scope of its actions beyond the traditional area of operations; Central America and the Caribbean. Significant operations included the United States and United Kingdom–planned 1953 Iranian coup d’état, the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion targeting Cuba, and support for the overthrow of Sukarno by General Suharto in Indonesia. In addition, the U.S. has interfered in the national elections of countries, including Italy in 1948,[1] the Philippines in 1953, Japan in the 1950s and 1960s,[2][3] Lebanon in 1957,[4] and Russia in 1996.[5] According to one study, the U.S. performed at least 81 overt and covert known interventions in foreign elections from 1946 to 2000.[6] According to another study, the U.S. engaged in 64 covert and six overt attempts at regime change during the Cold War.[7]

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States has led or supported wars to determine the governance of a number of countries. Stated U.S. aims in these conflicts have included fighting the war on terror, as in the Afghan War, or removing supposed weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), as in the Iraq War.

And that’s just the U.S.

Incidentally, the name of chief artist who built the sanctuary in the Wilderness, Betzalel, actually means, “In the shadow of God.”

It was late in the summer on 1995 when I first connected to the Web. I was playing around with this new supernatural toy from a company called “Gateway,” when suddenly the pearly gates opened, and I was in what they call a chat room. I looked up at the top of a pretty blank screen and saw that there were only two names there, and one of them was me. Well. not really me, but my screen name. Hamrab.

The other person was called Whalermouth. I tried to figure out what that meant, but then figured that if that other person was trying to do the same with my name he’d be having a hell of a time. It wasn’t worth trying to shake the anonymity.

Then, my four-year-old son Ethan noticed some words on the screen. “Hello, Hamrab, tell me if you are there.”

My God, it talks! The computer was talking to me. Or really, some completely unknown yet distinct person, with the image of God, yet totally unseen and unheard, someone was reaching out to me as a human being in this most inhuman of environments. What was I to do?

I wasn’t ready for this. Do I answer? Do I let on that I’m really there? Well, I typed in, “Hamrab says hello.” Totally flustered, and not wanting to get involved with anyone who would call himself Whalermouth, I clicked my way out of the room and to a local weather report. It was an easy click, much easier than hanging up the phone on all those solicitors who call at dinner time. Too easy, in fact. Because the human factor had been so masked by words on a screen. I’m not even sure why I said hello in the first place.

The fact that my son was there is not in itself significant, except that, well, you see he had helped me to turn the thing on. You know someday, maybe when he’s 16, he’ll be able to hit a baseball further than his old man. And someday, like maybe when he’s six, he’ll be a few technological light years ahead of me. But that’s OK, because I know that my parents, when they were my age, were just pleased as punch that they could get decent black and white reception of Milton Berle if the rabbit ears were turned in the right way. That was the extent their technological prowess, back in those good old days when gophers were pesky animals, the net was what you caught flies in on a hot summer day, and the web, well that was where Dad had to string up his son’s baseball glove. Even Dad’s glove had a web. Even granddad’s.

God is all over the Internet, because of the net, because of the web. These are the metaphors for the Sacred that resonate in this age: the images of universal connection.

Here’s the aforementioned “Foul Play” clip:

A.I. would actually be funny… if it weren’t going to destroy us all.

But aside from being funny, can it take on other overtly Jewish characteristics? Can it kvetch? I asked ChatGPT to generate a brief paragraph of kvetching, and here’s what I got.

Ugh, I can’t believe how ridiculously hot it is outside. And of course, my air conditioner decides to stop working right when I need it the most. The traffic today was a nightmare, too—so many reckless drivers cutting me off and making my commute unbearable. Oh, and don’t get me started on the never-ending chatter by the water cooler and stream of emails flooding my inbox. I swear, it’s like they multiply when I blink! Is it too much to ask for a day where everything goes smoothly for once? I’m just so tired of all these little annoyances piling up. Sigh.

Sigh? When did you ever hear a Jew say “sigh?” Unless we’re talking to a guy named Sy, we never say “sigh.”

And “ugh?” What Jew ever says “ugh?” It sounds like something that you would read in a comic strip – Peanuts or the Lone Ranger. And “Don’t get me started” is right out of Billy Crystal’s “Mr. Saturday Night.” And chattering? Who chatters? You chatter over finger sandwiches made of cucumbers, and not a pastrami at Katz’s Deli. Jews don’t chatter. We kvetch!

And in order to kvetch authentically, you need to be sitting down on one of those couches with the plastic covers like my grandmother had.

So, this A.I. generated kvetch sounds about as authentic as Billy Crystal channeling Eeyore, by way of Charlie Brown. It might as well have said, “Good grief!”

No comments:

Post a Comment