Mensch•Mark For Elul 19: Sharp Discussion with Students - Pipul HaTalmidim

Vigorous dialogue is a hallmark of Jewish learning. But how does one argue with a populist, especially one bent on spreading Big Lies?

About the Mensch•Mark Series

The Talmudic tractate Avot, 6:6 provides a roadmap as to how to live an ethical life. This passage includes 48 middot (measures) through which we can “acquire Torah.” See the full list here. For each of these days of reflection, running from the first of Elul through Yom Kippur, I’m highlighting one of these middot, in order to assist each of us in the process of soul searching (“heshbon ha-nefesh”).

Today’s Middah:

Sharp Discussion with Students - Middah Pipul HaTalmidim

URJ’s Take:

Text

"Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina said: What is implied by the verse 'Iron sharpens iron' (Proverbs 27:17) It tells you that just as one piece of iron sharpens another, so two scholars sharpen each other's mind by discussion of the Law." (Sefer Ha Aggadah - Legends of the Jews, 428:260)Commentary

Intense debate and discussion have a long history in Jewish tradition. As early as the book of Genesis we read of Abraham debating with God the destiny of the citizens of Sodom and Gomorrah. It was through debate that Abraham learns that there are no righteous people in these cities and therefore they do not merit being saved.The middah of pilpul hatalmidim teaches two values: the value of debate and the value of learning with others.

Debate sharpens one's mind and makes the subject under discussion clearer. As the Text asserts, "iron sharpens iron." Spirited and learned discussion elevates one's thinking. It pushes one to higher realms of learning, thinking, and understanding.

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch taught,

"Isolation is incompatible with Jewish knowledge; it is only by association with living sages, in close communion with associates, and by the clarity of thought and judgment that can be attained by teaching it to disciples that the knowledge of Torah can be nurtured and allowed to flourish." (Chapters of the Fathers, Hirsch p.105)

Simply put, one must combine a relationship with sages, a closeness with colleagues, and sharp discussion with students in order to tap all the resources of Torah knowledge. (Pirkei Avos, ArtScroll, p. 415)

Rabbah bar Bar Hanah said:

"Why are words of Torah likened to fire, as in the verse, 'Is not My word like fire? says Adonai' (Jeremiah 23:29) To teach you that just as fire does not ignite itself, so words of Torah do not abide in one who studies alone."

Simply put, we are to be samayach b'chelko—satisfied with our portion from the effort we expend in life whether it is in acquisition of material possessions or acquisition of skills and knowledge not the number of possessions we have or the level of learning we achieve. It is in the doing, not the acquiring, that satisfaction and happiness are to come.

My Take: How to argue against populism and the Big Lie

I happily lend this space to the late, great Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, who labeled Korach as the “first populist.” Even when Rabbi Sacks - who died of cancer in 2020 - wrote this in 2018 he could not have imagined what we would be dealing with just a few years later - a violent insurrection instigated by a Big Lie in Washington and a Prime Minister of Israel trying to cling to power by libeling his opponents as traitors. As it becomes more and more common to see leaders in supposedly "safe" democracies following the autocrat’s playbook, the lessons of Deuteronomy become more relevant than ever before. (And if you need a primer on how to recognize when autocracy is winning out, read this from Timothy Snyder).

Take it away, Rabbi Sacks! See the original essay here.

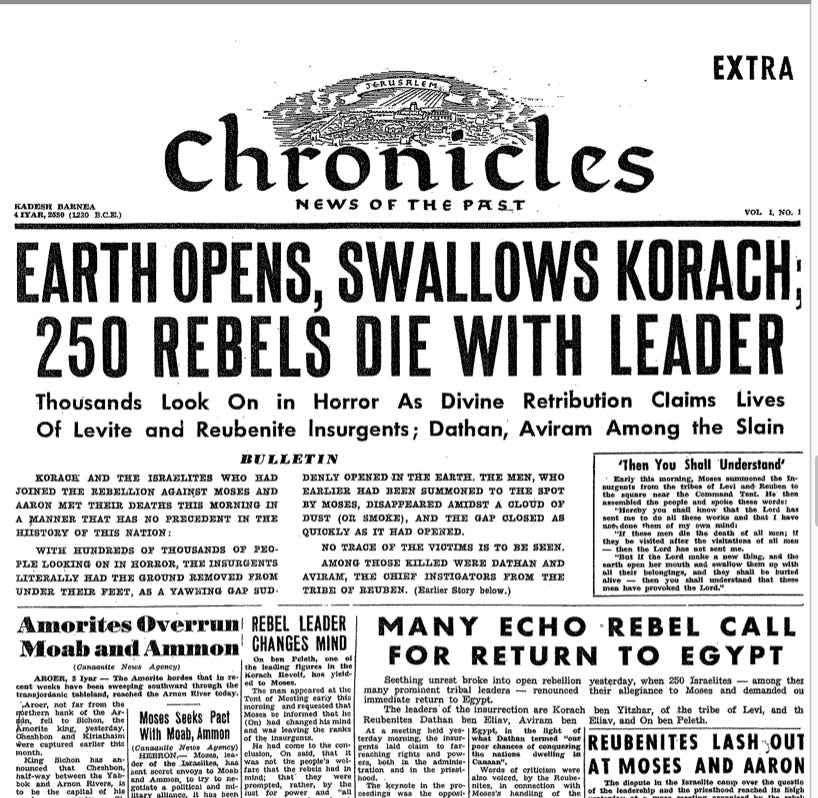

The Korach rebellion was a populist movement, and Korach himself an archetypal populist leader. Listen carefully to what he said about Moses and Aaron: “You have gone too far! The whole community is holy, every one of them, and the Lord is among them. Why then do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of the Lord?” (Num. 16:3).

These are classic populist claims. First, implies Korach, the establishment (Moses and Aaron) is corrupt. Moses has been guilty of nepotism in appointing his own brother as High Priest. He has kept the leadership roles within his immediate family instead of sharing them out more widely. Second, Korach presents himself as the people’s champion. The whole community, he says, is holy. There is nothing special about you, Moses and Aaron. We have all seen God’s miracles and heard His voice. We all helped build His Sanctuary. Korach is posing as the democrat so that he can become the autocrat.

Next, he and his fellow rebels mount an impressive campaign of fake news – anticipating events of our own time. We can infer this indirectly. When Moses says to God, “I have not taken so much as a donkey from them, nor have I wronged any of them” (Num. 16:15), it is clear that he has been accused of just that: exploiting his office for personal gain. When he says, “This is how you will know that the Lord has sent me to do all these things and that it was not my own idea” (Num. 16:28) it is equally clear that he has been accused of representing his own decisions as the will and word of God.

Most blatant is the post-truth claim of Datham and Aviram: “Isn’t it enough that you have brought us up out of a land flowing with milk and honey to kill us in the wilderness? And now you want to lord it over us!” (Num. 16:13). This is the most callous speech in the Torah. It combines false nostalgia for Egypt (a “land flowing with milk and honey”!), blaming Moses for the report of the spies, and accusing him of holding on to leadership for his own personal prestige – all three, outrageous lies.

Ramban was undoubtedly correct[3] when he says that such a challenge to Moses’ leadership would have been impossible at any earlier point. Only in the aftermath of the episode of the spies, when the people realised that they would not see the Promised Land in their lifetime, could discontent be stirred by Korach and his assorted fellow-travellers. They felt they had nothing to lose. Populism is the politics of disappointment, resentment and fear.

For once in his life, Moses acted autocratically, putting God, as it were, to the test:

“This is how you shall know that the Lord has sent me to do all these works; it has not been of my own accord: If these people die a natural death, or if a natural fate comes on them, then the Lord has not sent me. But if the Lord creates something new, and the ground opens its mouth and swallows them up, with all that belongs to them, and they go down alive into Sheol, then you shall know that these men have despised the Lord.” (Num. 16:28-30).

This dramatic effort at conflict resolution by the use of force (in this case, a miracle) failed completely. The ground did indeed open up and swallow Korach and his fellow rebels, but the people, despite their terror, were unimpressed. “On the next day, however, the whole congregation of the Israelites rebelled against Moses and against Aaron, saying, ‘You have killed the people of the Lord” (Num. 17:6). Jews have always resisted autocratic leaders.

What is even more striking is the way the sages framed the conflict. Instead of seeing it as a black-and-white contrast between rebellion and obedience, they insisted on the validity of argument in the public domain. They said that what was wrong with Korach and his fellows was not that they argued with Moses and Aaron, but that they did so “not for the sake of Heaven.” The schools of Hillel and Shammai, however, argued for the sake of Heaven, and thus their argument had enduring value.[4] Judaism, as I argued in Covenant and Conversation Shemot this year, is unique in the fact that virtually all of its canonical texts are anthologies of arguments.

What matters in Judaism is why the argument was undertaken and how it was conducted. An argument not for the sake of Heaven is one that is undertaken for the sake of victory. An argument for the sake of Heaven is undertaken for the sake of truth. When the aim is victory, as it was in the case of Korach, both sides are diminished. Korach died, and Moses’ authority was tarnished. But when the aim is truth, both sides gain. To be defeated by the truth is the only defeat that is also a victory. As R. Shimon ha-Amsoni said: “Just as I received reward for the exposition, so I will receive reward for the retraction.”[5]

In his excellent short book, What is Populism?, Jan-Werner Muller argues that the best indicator of populist politics is its delegitimization of other voices. Populists claim that “they and they alone represent the people.” Anyone who disagrees with them is “essentially illegitimate.” Once in power, they silence dissent. That is why the silencing of unpopular views in university campuses today, in the form of “safe space,” “trigger warnings,” and “micro-aggressions,” is so dangerous. When academic freedom dies, the death of other freedoms follows.

Hence the power of Judaism’s defense against populism in the form of its insistence on the legitimacy of “argument for the sake of Heaven.” Judaism does not silence dissent: to the contrary, it dignifies it. This was institutionalized in the biblical era in the form of the prophets who spoke truth to power. In the rabbinic era it lived in the culture of argument evident on every page of the Mishnah, Gemara and their commentaries. In the contemporary State of Israel, argumentativeness is part of the very texture of its democratic freedom, in the strongest possible contrast to much of the rest of the Middle East.

Hence the life-changing idea: If you seek to learn, grow, pursue truth and find freedom, seek places that welcome argument and respect dissenting views. Stay far from people, places and political parties that don’t. Though they claim to be friends of the people, they are in fact the enemies of freedom.

No comments:

Post a Comment