Liberation of Auschwitz, 80 Years On: From Sorrow to Song

Plus, book excerpt: "Winding Paths to a Wounded God" - Four possibilities for understanding God in light of the most ungodly event of all time.

Monday is International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Auschwitz was liberated 80 years ago, on January 27, 1945.

Also see this list of dozens (actually hundreds) of excellent books about the Holocaust.

Here is a packet containing detailed responses to five common Holocaust denial claims.

Click here for a timeline and facts about the Holocaust (MyJewishLearning)

What was Auschwitz? (Encyclopedia of the Holocaust)

From Sorrow to Song

The 20th-century Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote, "There are three ways in which we respond to sorrow. On the first level, we cry; on the second level, we are silent; on the highest level, we take sorrow and turn it into song." 1

These responses to tragedy mirror how Jews have responded to the Holocaust over the past eight decades, from overwhelming grief to numbed silence. Today, as we commemorate the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the time has come to turn the sorrow into song - in a sense, to “embrace” Auschwitz.

Let me be clear: There was nothing good about the Holocaust. What happened during the period of Nazi hegemony over Europe was the nadir of human history. No other event is remotely comparable. It is difficult to conceive of an atrocity so maliciously designed and meticulously carried out on so vast a scale.

I've spent the better part of my career as a rabbi and writer trying to reframe Judaism in positive terms. For me that means steering the conversation away from the Holocaust, lest my own faith wither on the vine. This historic black hole poses questions that are unanswerable, eclipsing centuries of Jewish achievement, nurturing neurosis. It gave us an excuse to hate, and it gave our children an excuse to opt out of being Jewish altogether: Who would want to be part of such a hopeless, hapless people?

But recently I've discovered that the opposite is true. Judaism is being interpreted anew through the prism of this epochal event. We are hearing the first stirrings of a song.

I spelled this out in my book, Embracing Auschwitz: Forging a Vibrant, Life-Affirming Judaism that Takes the Holocaust Seriously, published by Ben Yehuda Press.2

Throughout Jewish history it has become axiomatic that approximately 7-8 decades after an enormous disaster, new creative expressions of faith have surfaced. Just as Jews traditionally rise from mourning a loved one on the 8th day 3, so do we rise collectively from trauma as we reach the eighth decade.

That’s the approximate span of time that passed after the first temple was destroyed in 586 B.C., when King Cyrus restored hope to a Jewish people who had already begun adapting their religion to the new realities of residing in exile by the rivers of Babylon. The second temple’s construction was completed in about 515.

Eight decades after the massacres of the First Crusade in 1096, dramatic changes began to revolutionize Jewish philosophy and law - Maimonides completed his commentary on the Mishna in 1168 and his great law code, the Mishna Torah, in 1180. Approximately 80 years after the expulsion from Spain in 1492, which displaced 200,000 Jews and resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, Jewish life was replanted in Safed, Palestine, and it came to full flower with the works of the Kabbalists and the publication of the great law code, the Shulchan Aruch, in 1565.

The year 1648 was a dark one for Eastern European Jewry, as a Cossack revolt killed upwards of 100,000 Jews. Almost exactly 70 years later, Israel Ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov, introduced Hasidism to Polish Jews. In early Hasidic literature, the Baal Shem Tov's followers saw a direct historical link from the ordeals of 1648 to their teacher's ministry, asserting that this charismatic leader "awakened the people Israel from their long coma and brought them renewed joy in the nearness of God."

Now, eighty years past the liberation of Auschwitz, we have a new opportunity. What needs to happen?

First, Jews need to embrace the obligation to be surrogate witnesses as the last group of actual witnesses departs.

Elie Wiesel said that to listen to a witness is to become one. What Jews were charged to do at Sinai - to be pillars of morality, a nation of priests - now takes on an added urgency. All Jews need to learn how to tell the witnesses' stories with love and conviction and with bursting pride at their incomprehensible acts of heroism and faith.

This historic black hole known as the Holocaust poses questions that are unanswerable, eclipsing centuries of Jewish achievement and nurturing neurosis. It gave us an excuse to hate, and it gave our children an excuse to opt out of being Jewish altogether. Who would want to be part of such a hopeless, hapless people?

Second, we need to recognize that the Holocaust has taken its place at the very core of what it means to be Jewish.

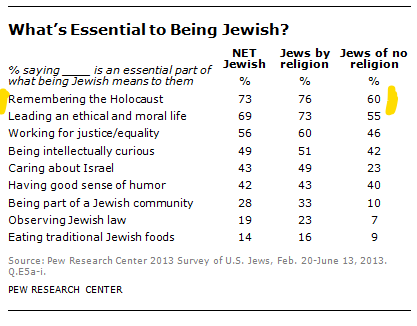

The 2013 Pew survey of American Jewry asked, "What does it mean to be Jewish?" providing respondents nine suggested Jewish activities and attributes from which to select those deemed "essential." Just 19% chose "Observing Jewish law." By far the leading answer was "Remembering the Holocaust," at 73%.

You can't get three-quarters of American Jews to agree on anything, not even what to put on a bagel. If there is to be a core to our self-image as Jews, it is far more likely to come from Auschwitz than from Sinai. We know as well that Israeli Jews and American Jews don't agree on much these days, but when Israeli Jews were asked the same question, the result was nearly identical.

The Holocaust, in short, is our greatest common denominator. Any expression of Judaism to emerge from the modern era must have the Holocaust at its core, or it will not be authentic.

But just as it cannot deny the abyss, any modern expression of Judaism must also speak to the need to affirm joy, beauty, renewed life and at least the possibility of a responsive divinity, or it will not survive.

The Torah of Sinai, the backbone of rabbinic Judaism, now has a companion narrative that I call the Torah of Auschwitz, sacred teachings and practices that have begun to coalesce into a canon, enabling us to confront the darkest demons of eight decades ago. At the same time, this narrative is filled with positive and life-affirming lessons for the entire world.

Just as the evil perpetrated by the Nazis has no historical parallel, so, too, does the valor of the Holocaust era dwarf anything we have ever seen, even in the Bible. When it comes to pure courage and unfathomable love, Joshua, Miriam and David can't hold a candle to the stories of Janusz Korczak, Mordecai Anielewicz and Hannah Szenes. The prophetic proclamations of Jeremiah and Isaiah are mirrored - and perhaps surpassed - by the immortal words of such modern-day prophets as Primo Levi and Viktor Frankl.

As for Oskar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg and over 11,000 Righteous Gentiles honored at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial, the modern-day Righteous Gentile really has no parallel in the Hebrew Bible. When the Israelites were slaves in Egypt, no one offered to take them in. (Okay, Pharaoh's daughter took in baby Moses, but that's it.)

How can we not burst with pride at the poetry, the scraps of food shared; the secret Seders; the impossible escapes; the artwork of the beautiful children of Terezin; how the victims were able to maintain their dignity and humanity in the most inhuman conditions, protecting their loved ones - even somehow falling in love?

If there is to be a core to our self-image as Jews, it is far more likely to come from Auschwitz than from Sinai.

Anne Frank, so eternally appealing is her very ordinariness, has already become a universal symbol of innocence and steadfast optimism in the face of pure evil, eclipsing ancient heroines like Ruth and Esther in our collective imagination. She has inspired multiple dramas, films and novels and drew 1.3 million visitors to her secret annex in Amsterdam in 2016 alone. The Torah of Auschwitz that is now emerging will feature her wisdom as its book of Proverbs and Elie Wiesel's "Night" as its Book of Job.

The Torah of Auschwitz 4 has already transformed religious practice and biblical interpretation. The injunction to remember the evil perpetrated by Amalek, recorded in the Book of Deuteronomy, has metamorphosed into the post-Holocaust rallying cry, "Never again."

It is said that every Jew, past, present and future, stood at Sinai. Every Jew also stood, metaphorically, in those gas chambers as well. It didn't matter whether you were male or female, traditional, liberal or secular, born Jewish, converted to Judaism or married to a Jew - or even merely the grandchild of a Jew. The Holocaust has given us a common point of departure, a place where we were all present, even if we weren't. Jewish unity, to the degree that it can be reestablished at all, is attainable only in the context of that shared experience and the affirmation that Auschwitz must never happen again.

Given that we now have the massive wounds to tend to post-October 7, for us and for those around us, it becomes even more essential that we find ways to integrate the enormity of the Holocaust into our story, rather than rejecting or downplaying it. It is who we are.

When Jews invoke Auschwitz, the world listens - because we were there. Many hate us for that, especially if they fetishize fascism. Others admire us. But everyone listens.

Let us sing.

I present here a full chapter from Embracing Auschwitz: Forging a Vibrant, Life-Affirming Judaism that Takes the Holocaust Seriously, in which I present four possibilities for understanding God in light of the most ungodly event of all time. I pose these more as questions than answers, in the hope that the conversation can continue to nurture a new sense of faith, both among those who profess to believe and those who don’t.

Chapter Nine

THE BOOK OF UNRELENTING QUESTIONS

Winding Paths to a Wounded God

We’ve got God the artist and the standup comic. God laughs, God creates, God peeks through randomly. But can any of these Gods save?

The experience of the Holocaust stands alone in history, a godless counterpoint to all things sacred. Alongside the majestic peaks of Sinai and Zion, our view now includes this man-made mountain of children’s shoes, empty luggage and echoing shrieks, a clump of human refuse that dwarfs everything around it, taller than Sinai, more imposing than Zion, more insurmountable than Everest.

Throughout this book, I’ve addressed the issue of God somewhat peripherally, offering a few possibilities for understanding the divine in light of the most ungodly event of all time. I’ve suggested equating God with the life force within all living creatures (chapter one), as a source of vision (chapter four), and as a purveyor of unity (chapter seven). But the Torah of Auschwitz is a human-centric document. It is a fool’s errand to attempt to explain God’s ways in a Holocaust setting. As Rabbi Irving (Yitz) Greenberg has explained, any theological explanation for the Shoah must consider the specter of living babies being thrown into flames. If your understanding of God can survive that and still be coherent, all power to you.

The great Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai presented the matter succinctly in his 1999 poem, “After Auschwitz.”

After Auschwitz, no theology:

From the chimneys of the Vatican, white smoke rises --

a sign the cardinals have chosen themselves a Pope.

From the crematoria of Auschwitz, black smoke rises --

a sign the conclave of Gods hasn't yet chosen

the Chosen People.

After Auschwitz, no theology:

the inmates of extermination bear on their forearms

the telephone numbers of God,

numbers that do not answer

and now are disconnected, one by one.

After Auschwitz, a new theology:

the Jews who died in the Shoah

have now come to be like their God,

who has no likeness of a body and has no body.

They have no likeness of a body and they have no body.

Even Amichai, the inveterate skeptic, seeks a theological basis for a world that can include both God and the Holocaust. We are drawn to theological speculation as moths to a flame. Some say we have a “religious instinct,” asserting that if there were no God we would be compelled to invent one. Whether or not that’s true, it’s worthwhile to explore new ways to imagine God, ones that do no shame to the memory of the abandoned martyrs.

While humbly acknowledging that post Holocaust God-talk is often a fool’s errand, allow me to offer some theological saplings from which a post-Auschwitz theology might germinate (somehow that word seems inappropriate), with the understanding that these are not intended to be comprehensive treatises, but simply kernels to provoke thought:

The God of Toyota and the God of Chelm

In the spring of 2010, as I prepared to face the enormity of Auschwitz for the first time on the March of the Living, that annual gathering of thousands of Jewish teenagers in Poland, it occurred to me that since the Shoah, rabbis have become like Toyota salesmen. At that time Toyota was going through an existential crisis, having had to recall 7.5 million vehicles because gas pedals were getting stuck and people were dying as result. The company was faced with a branding catastrophe.

Let’s play this analogy out. What, after all, is religion selling but a product once universally revered but now questioned. The myth has been detonated, the brand exposed. Just as the 2010 Toyota crisis evoked memories of a time when “Made in Japan” was considered derogatory (meaning cheap, fake, laughable), after the Holocaust, the “Made at Sinai,” Torah suddenly feels too fragile and cheaply designed, like the postwar version of “Made in Japan.”

To be frank, we clergy have been trained too well to contain the damage, having been taught numerous diversionary strategies when the Holocaust comes up, enabling us to refocus the question (“Where was God? Well, where was MAN?”) or simply foster a perpetual state of denial (“We can’t know God’s ways”). Some have chosen to relinquish some of God’s omnipotence, others go much farther. But for the most part, we hammer home the message that religion still has an important function to serve, even if there’s a gaping hole under the hood.

Some deny that the hole exists, clinging naively to pre-Auschwitz fantasies. It is astonishing how many otherwise intelligent, modern, skeptical Jews still adhere to the old, omnipotent “what-me-worry” patriarchal Santa-God in the sky, slickly packaged by various groups, as if the Holocaust had never happened. But most rabbis, while not denying the seriousness of the challenge, prefer to set the questions aside and punt, suggesting that maybe the next generation will gain the insight to solve the problem. I for one, have become an expert punter.

Over the decades, there have been noteworthy attempts to deal with this dilemma. Some, like Richard Rubenstein, writer of the existentialist treatise, “After Auschwitz,” have been powerfully honest. Radical theologies like his proliferated in the ‘60s, during the so called “Death of God” era. Since then, God has managed to survive quite nicely, thank you, while those bold theologies have yellowed with age.

Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971) offered that “God” is simply a metaphor for God, in other words, we shouldn’t get too hung up on any name or particular image of what God looks like or does. Harold Kushner, in “When Bad Things Happen to Good People,” offered a post-Holocaust notion that God can no longer be seen as omnipotent, but that God is found in the love that enables us to recover from tragedy. I lean in that direction, but it sounds a bit too convenient for us to be able to mold God in our image, according to our current theological needs, while divorcing God from the responsibility of evil. It makes God sound too clever by half, parsing responsibility onto some other god over there.

Many Jews are choosing more Kabbalistic imagery, which imagines God more as a system of forces, or emanations, in a carefully balanced yin-yang type of universe.

Many are groping for a metaphor that allows for a more complicated, wounded deity, or at the very least a not-so-omniscient one, or perhaps a preoccupied one, or one who was simply asleep on the job. The question of Auschwitz remains as vivid as ever, but after seven decades, many seem to be tiring of asking why and have given up on God altogether.

The Torah of Auschwitz compels us to continue that unrelenting questioning and not to give up on God so easily, whether or not God has given up on us.

Toyota eventually solved their branding problem, but if they hadn’t, one wonders whether the marketers would have eventually worn us down by constantly repeating old canards.

Would we all have started believing in their product again, even without discernable evidence of improvement? Would we have eventually tired of asking the questions?

Is the same true of God? Would we go back to clinging to naïve superstitions, simply because they are more comfortable than the yawning, hopeless abyss that awaits those who dabble in a godless universe?

Would we eventually accept intellectually comatose rationalizations like the one made by an Ultra-Orthodox rabbi in Israel, who claimed that God caused a bus accident to occur because a mezuzah hanging on a passenger’s door at home was not kosher?

Perhaps the antidote to such spurious speculation is to leave the realm of logic altogether – though without abandoning our skeptic’s scalpel. Perhaps the answer is to accept a dash of madness with our theology.

In 2010, the day after I marched at Auschwitz with the teens 5, my group stopped off on the way to Warsaw in a quaint town called Chelm, which for Jews is the eternal capital of absurdity. Chelmites are mythical Jews from a real town, known for their propensity to take logic to its bizarre extreme.

Two men of Chelm went out for a walk, when suddenly it began to rain. "Quick," said one.

"Open your umbrella."

"It won't help," said his friend. "My umbrella is full of holes."

"Then why did you bring it?"

"I didn't think it would rain!"

A New York based Klezmer group named Golem wrote a song about a Chelmite who leaves on a journey to Warsaw, gets lost and ends up back in Chelm. "He's so stupid that he thinks he's actually in Warsaw,” bandleader Annette Ezekiel told SPIN.com. “The moral is, any place can be any place else – it doesn't matter where you are.”

But for me it mattered a lot, that this journey from Auschwitz, the darkest place in Jewish history, led directly to Chelm, the most absurd. Chelm was the place where I could wash and purify my hands after visiting the countrywide graveyard that is Poland, a way station before heading to Jerusalem for the second part of the March.

Two points about Chelm: First, for the storytellers, laughter provided a great outlet from hunger, poverty and hatred, of which the Jews of Poland had no shortage. But rather than laugh at real people, the genius of these storytellers was that they invented a mythical community to laugh at. Yes, the people of Chelm were not really bumbling idiots. Not only is that practical (as opposed to laughing at Poles, who might have responded by killing them), it is far more ethical to make fun of fake people than real people. So instead of telling Polish jokes, Jews told Chelm jokes.

Second, Chelm might hold the key to our getting beyond the theological quandaries of our age. If the commanding voice of Auschwitz has muffled the God of Sinai for the time being, maybe we need to pay more attention to the God of Chelm. The Yiddish aphorism, “ Man plans, God laughs,” just might be the most apt theological response to an age of absurdity. It’s not that God is laughing at us, simply that God has taught us that laughter is the only way one can respond to a world of unfathomable evil and unspeakable tragedy, while clinging to life and dignity.

Maintaining some semblance of sanity requires a modicum of insanity; it’s an art we’ve been perfecting for centuries, ever since we figured out how a poor peasant living in rags could be transformed into royalty through the simple act of lighting candles, drinking wine and blessing bread on a Friday night. If that isn’t a little taste of madness, what is?

The first Jewish kid, whose life was replete with tragedy, was nonetheless named laughter (Isaac). We’ve been re-living Isaac’s story ever since.

Whatever enables us to escape from a bitter and unjust reality can help to preserve our essential humanness. Jews were quixotic long before Quixote, waving at windmills and looking perfectly ridiculous while clinging to their dignity in the most undignified of settings.

Elie Wiesel often told this Holocaust-based modern midrash about the significance of flailing at windmills in the ancient, corrupt city of Sodom:

“One day a Tzadik (righteous person) came to Sodom; He knew what Sodom was, so he came to save it from sin, from destruction. He preached to the people. "Please do not be murderers, do not be thieves. Do not be silent and do not be indifferent."

He went on preaching day after day, maybe even picketing. But no one listened. He was not discouraged. He went on preaching for years. Finally, someone asked him, "Rabbi, why do you do that? Don't you see it is no use?"

The first Jewish kid, whose life was replete with tragedy, was nonetheless named laughter (Isaac). We’ve been re-living Isaac’s story ever since.

He said, "I know it is of no use, but I must. And I will tell you why: in the beginning, I thought I had to protest and to shout in order to change them. I have given up this hope. Now I know I must picket and scream and shout so that they should not change me."

And picking up on this theme of absurdity, Woody Allen6 ends his classic film, Annie Hall with a similar story containing a perfect message for the Torah of Auschwitz:

“A guy walks into a psychiatrist's office and says, hey doc, my brother's crazy! He thinks he's a chicken. Then the doc says, why don't you turn him in? Then the guy says, I would but I need the eggs. I guess that's how I feel about relationships. They're totally crazy, irrational, and absurd, but we keep going through it because we need the eggs.”

Despite the near impossibility of accepting theological explanations for God’s silence during the Holocaust, we still need the eggs – we still need to struggle with a notion of God, and the possibility of a just universe and a hopeful existence. And who says we can’t struggle and giggle at the same time?

The God Particle

Here’s another God-option from the Torah of Auschwitz.

In October of 2012, on the night that Hurricane Sandy roared in, two giant trees sandwiched my house and pierced the garage roof. It felt like the world itself was crashing down, as if I was witnessing before my eyes an undoing of Creation’s primal act. In Genesis, a wind brought about a separation of earthly and heavenly waters, and then a separation of water from dry land. But with Sandy, the waters of the deep appeared to be reclaiming that coastline and undoing that initial act of separation. It felt apocalyptic.

During that season of Sandy, I did some exhaustive research on the Mayan Apocalypse – which was subject to immense speculation late that year. According to an ancient Mayan prophecy, the world was scheduled to come to an end on December 21. On the plus side, had that prophecy come true, Jews would have been able to squeeze in all eight days of Chanukah (sorry, no Christmas). On the minus side, the world would have ceased to exist.

But my research turned up a different vision. According to Guatemalan author Carlos Barrios, that fated date of December 21, 2012 marked not the end of time as Hollywood would imagine it, but the beginning of a change in consciousness, when “a new socioeconomic order will arise in harmony with Mother Earth.” These beliefs all revolve around the winter solstice coinciding with the Earth’s being located at a point of particular balance, midway through the Milky Way.

What we have with the Mayans, then, at least in some people’s estimation, are cycles of creation and destruction, leading not to an apocalypse, but rather to a time of eternal peace and bliss – a better time, not an end time at all.

It all sounds very, well, Jewish. Midrash Genesis Rabbah cites Rabbi Abahu’s claim that God created numerous universes prior to the creation of this one. Each time that God created a universe, something went wrong and the experiment was discarded. But when this one was created, God looked around and saw that it was very good. Our version of the cosmos was a keeper. This one God could work with.

What a great story. It teaches us that for the ancient rabbis, not even God could determine in advance whether a given world would work out. There were apocalypses aplenty. But this teaching leads inevitably to the question, why has this world has not been destroyed? And the answer is either 1) it hasn't been destroyed yet; or 2) because this time, for this cosmos, creatures called human beings have entered into the picture, and they’ve demonstrated a capacity to grow and adapt. This midrash adds that the entire cosmos possesses the same innate ability to regenerate.

A few years ago, scientists reveled in the discovery of the Higgs Boson, or so called “God particle.” In my layman’s understanding, this subatomic particle somehow takes mass and propels it into energy. It drives everything forward, and in doing so, it enables existence to happen.

Maybe this little particle, seen from a more theological standpoint, is also that microscopic spark of divinity that pushes us to get up when we’ve fallen, like that panic button seniors wear. Even if we are physically unable to rise from the floor, there is something pushing us to live on. We’ve got the God particle. And we’ve learned that not only is it in our DNA, it’s in our every atom. It’s implanted into the workings of the universe.

So despite the Holocaust and all the inexplicable evil around us, God imbedded within us a gift that no prior creation received, the gift of a second chance…and a third, and as many chances as we need, to rise from the ashes.

There is something in our makeup that keeps pushing us forward.

In chapter two I spoke about that inner drive to “choose life” that propelled the Candy Man and Elijah Girl, the same one that lends sweetness to the freezing carrot and has boosted the against-all-odds revival of the Jews of Budapest. Here I’m going one step beyond that conscious will to live; I’m suggesting that the drive is not a choice at all, but something embedded within us, and I give that life-force a name. For lack of a better one, I call it “God.”

Even if we are physically unable to rise from the floor, there is something pushing us to live on. We’ve got the God particle. And we’ve learned that not only is it in our DNA, it’s in our every atom. It’s implanted into the workings of the universe.

The survival instinct goes beyond free will. We recognize that when we try to hold our breath until our bodies force us to submit and breathe. Even after Auschwitz, there is something pushing life forward. It is the God particle, and it is in us all.

The Shadow of God

In the Torah of Auschwitz, the path back to God is littered with shattered dreams, flavored with a strong sense of the absurd mixed with a pinch of wonder. We remain attuned to the possibility of an orderly universe, despite all that we have witnessed.

Borrowing from a term utilized by physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn, Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi sees our new era as a “Paradigm Shift,” post monotheistic, post patriarchal, more universal and syncretistic. One might quibble with the details, but it’s clear that we have entered a time of theological creativity, equaled perhaps only by the Axial Age twenty five centuries ago, when theological giants from Buddha and Jeremiah to Confucius and Homer changed everything.

If we allow ourselves to be swept up by these new winds, maybe the scent of sanctity might be sniffed through the swaying treetops. Maybe God can appear to us again – and if not God, or even a crescent of the eclipsed God, perhaps the shadow of God.

Betzalel was the leading artist of the Torah of Sinai and designer of the tabernacle in the wilderness, mentioned first in Exodus. His name means “in the shadow of God.” It is through the mind of the artist that a new sanctuary will be designed, allowing us, if we are fortunate, brief glimpses of the divine silhouette.

It says in the Talmud (Avot), "In a place where there is no humanity, try to be human.”

And how do we do that? We don our smock, we pick up the brush, and we begin to paint a picture of such beauty and goodness that it could survive even its own destruction. Even if we are swallowed up by the evil around us, as Anne Frank did, the art remains, her words remain, rising above even the smoky pyres of Bergen-Belsen; much as occurred during the Hadrianic persecutions of the second century, when Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion, wrapped in a Torah scroll while being burned at the stake, exclaimed, “The parchment is being burned but the letters are flying free!”

The art becomes the affirmation, and within that affirmation glows the penumbra of God’s shadow.

Numerous stories of transcendent artistry have emerged from the Holocaust.

In March of 2018 in the southern development town of Yeruham, Israeli schoolchildren performed lost music written by Jews during the Shoah. An article in Ha’aretz describes how conductor Francesco Lotoro chastened his musicians, consisting of twenty teenagers dressed in jeans, sneakers and T-shirts, “to convey the desperate passion and dramatic tension of a tango written in the Nazi death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“Der Tango fun Oshwientschim”– as the anonymous Yiddish song is titled – is part of the core repertoire of this orchestra, which is dedicated to playing music composed during the Holocaust.

The article describes how Lotoro “has made it his life’s mission to find, preserve and popularize music that was composed by Jews and other prisoners during World War II – from entire operas written on toilet paper in Nazi camps to love songs created by POWs from all sides of the conflict.” He’s salvaged 8,000 musical compositions created by Jews during that darkest of times in the darkest of places.

Lotoro cites the example of the imprisoned Czech composer Rudolf Karel, who wrote down a nonet (composition for nine instruments) and a five-act opera on toilet paper using medical charcoal, which he received because he was suffering from dysentery.

His works were smuggled out by a friendly guard, but Karel ultimately succumbed to exposure and dysentery in Terezin just two months before the end of the war in Europe.

“The paradox is that we have more music created in Birkenau, where there was extermination by gas, than in Auschwitz I, where there were also Poles, Soviets and it was a different kind of captivity,” Lotoro told Haaretz. “Where there is more danger of death, you create more music,” he says.

The art becomes the affirmation and within that affirmation glows the penumbra of God’s shadow.

Robert Mapplethorpe once said, “When I work, and in my art, I hold hands with God.”

The Torah of Auschwitz sees art as a path toward a restoration of the Sacred, as we join Betzalel in continuing to defy the darkness by designing sanctuaries, making music, writing poetry and dancing.

The great Isaac Stern, of blessed memory, was performing a concert in Jerusalem during the Gulf War in 1991, and he was interrupted by a siren warning of an Iraqi Scud missile attack.

After the audience put on gas masks, Stern returned to the stage and played a selection from Bach. He refused to wear a gas mask, in effect daring Saddam Hussein to silence the music.

Artists in extremis live in the shadow of God. But of all the artistic responses to catastrophe, none can match what I saw in Washington State. The canvas was Mount St. Helens and the artist - the artist in the shadow of God – was God.

On May 18th, 1980, the eruption of Mount. St. Helens in southwest Washington changed more than 200 square miles of rich forest into a gray, lifeless landscape. The lateral blast swept out of the north side at 300 miles per hour creating a 230-square mile fan shaped area of devastation reaching 17 miles from the crater. With temperatures as high as 660 degrees and the power of 24 megatons of thermal energy, it snapped 100-year-old trees like toothpicks and stripped them of their bark. The largest landslide in recorded history swept down the mountain at speeds of 70 to 150 miles per hour and buried the North Fork of the Toutle River under an average of 150 feet of debris. The massive ash cloud grew to 80,000 feet in 15 minutes and reached the East Coast in 3 days, circling the earth in 15 days. 7,000 big game animals, 12 million salmon, millions of birds and small mammals and 57 humans died in the eruption. Before the blast the mountain stood 9,677 tall. It now stands at 8,363 feet. A thousand feet of mountain is no more. Talk about destruction!

So, when I went there with my family in 2003, I expected to find an eerie moonscape, but I saw something absolutely amazing instead. The land around the mountain is slowly healing.

There is new growth everywhere, trees and moss and animal life. What in Auschwitz and Dachau had looked grotesque and manipulative (see chapter eight), like tampering with evidence at a crime scene, here looked astonishing and perfectly natural.

In fact, life returned to Mount St. Helens even before the search for the dead had ended. National Guard rescue crews looking for human casualties during the week after the 1980 eruption found that flies and yellow jackets had arrived before them. Curious deer and elk trotted into the blast zone just days after the dust settled. Helicopter pilots who landed inside the crater that first summer reported being dive-bombed by hummingbirds, which mistook their orange jumpsuits for something to eat. A whole new ecosystem began to emerge. Peter Frenzen, the chief scientist at Mount St. Helens, put it best, "Volcanoes do not destroy," he said, "they create."

As I looked out on all this creative destruction, I finally understand how Jews developed their proclivity for confronting madness with lightless, and absurdity with artistry. We inherited it from the God who renews Creation each day. Never was that more evident to me than at Mount St Helens.

So, to ask whether God’s brand has been permanently dented by the Holocaust is to ask the wrong question. Would you buy a used Toyota from this deity? Perhaps not. But the gift of artistry, which is a shadowy reflection of divine inspiration, has granted us the courage to stare directly into that gaping hole in the chassis and chuckle at the absurdity of it all, while gasping in amazement that, despite everything, we are alive. And if we are alive, there, in some manner, must be miracles, after all.

4) The Eclipse of “The Eclipse of God”

On the last Sunday of August, 2005, while Hurricane Katrina was battering the southern coast, I set out from Westchester airport on a flight to Chicago for the wedding of a close friend, which I would have the double pleasure of attending and performing. The plane pulled out to the runway about fifteen minutes late. No problem. We waited there another 15 minutes or so. That seemed a little strange, considering no other planes were landing or taking off. Finally the pilot got on the speaker and let us know that there had been some alarm lights blinking; it was probably a false alarm, he had seen this a few times before, and they needed to get a mechanic on board just to make sure.

An hour later, with passengers beginning to get restless, the pilot came on again. He told us it looked bad – that he was going to have to set the wheels in motion to have the flight cancelled. Mass hysteria followed as the cellphones came out and people frantically began making alternative arrangements. I just sat there. I felt terribly about the wedding but knew I was powerless to do anything about it. My friend is a rabbi – I wondered if Illinois law would allow him to perform his own wedding. But there was something in me that just wouldn’t let me panic, something reassuring me that things would turn out all right in the end.

A few minutes later, the pilot came on again. “Someone must really want you to get to Chicago. The problem has been solved and we’ll be departing in just a few minutes.”

Now I faced another dilemma – do I really want to take off for Chicago in this plane?

Again, I was calmed by an inner sense that things would be OK. We took off over two hours late and I made it to the wedding just in time.

As we were flying, I was speaking with the woman in the row behind me and we talked about the pilot’s line that someone wanted us to get to Chicago, and how surreal the whole experience had been. Was it all just coincidence or part of some master plan? Did Someone really want me to be at that wedding? Or was there another person on that plane with an even more important task, perhaps a task that that person was not even aware of? “It seems so odd.” I said.

The woman looked at me and replied, “You know the old saying, ‘Is it odd or is it God?

I did not reveal my secret identity. But I thought about the simplicity of the catchphrase – one that has been popularized by Twelve Step groups – and how it leaves so little room for a middle ground. And although I’m usually a bonafide shades-of-grey kind of guy, when I thought about it, she was right. Either everything is completely random, or it’s all part of some divine scheme.

For a Boston Red Sox fan like me, October 2004 was redemptive. Side by side in my office hang photos of Boston and Jerusalem. My exilic existence has been marked by a constant yearning for redemption in both of my ancestral homes. For one that meant a thriving Israel, freed from fear. For the other, for most of my life, it meant a Red Sox World Series championship.

Through the misty sky on Wednesday night, October 27, 2004, a ruddy moon glowed from behind the earth's shadow. At the precise time of the lunar eclipse, the Red Sox won the World Series. Some called this definitive proof that there is a God. 7

Too many things broke right for the Sox that year, too many of their prior indignities were undone in uncanny ways, for their improbable victory not to have somehow been written in the stars. Even before that season began, the Sox had couched this campaign in religious terms, unfurling a huge "Keep the Faith" banner above the Western Wall – I mean the Green Monster.

This would at last be the season when their 86-year-old “Curse of the Bambino” would be lifted. Their epic, seven game series with the Yankees played out these redemptive themes, carrying the Sox and their fandom from the brink of disaster to the greatest comeback seen since the Exodus, climaxing with the parting of the Red Sea, which is what Cardinal fans called their packed stadium. It all seemed so biblical.

True to my fatalistic Red Sox roots, I had expected yet another loss, a continuation of what Martin Buber called, in his classic 1952 essay, "The Eclipse of God," "the still unredeemed concreteness of the human world in all its horror." Buber’s paper, written shortly after the Holocaust, was an effort to rummage through the ashes for some way of understanding the incomprehensible and reconciling himself to a world without an operational deity.

But a half century after Buber, I witnessed the eclipse of Buber’s eclipse, and it was happening on my TV screen in real time. There was an actual lunar eclipse going on during the fourth and final World Series game, and the cameras kept focusing on that disappearing and reappearing moon over and over again. It was simply too God to be odd.

Among the dozens of congratulatory e-mails and calls I received the day after the Eclipse of the Curse, this message stood out: "In this world of so much discouraging news, how wonderful to have something to cheer about! The eclipse underscored this night of sports history and affirmed the importance and joy of believing in your dreams against all odds."

So against all odds, was it God?

And so, you might ask, how can we believe in a God so capricious as to allow millions to die in gas chambers and yet align stars to help a baseball team? Wasn’t this concept of “believing in your dreams against all odds” now officially dead, having been incinerated at the same place as one third of my people?

The Torah of Auschwitz leaves that question unanswered, but offers as consolation the absurdity of Chelm, the embedded God particle, the distilled, the silhouette of Betzalel’s divine artistry and the capriciousness of an occasional sublime breakthrough – what we in the religion biz call a hierophany. Maybe a slivered corona of an eclipsed orb can peek through from time to time, and maybe a dormant deity can somehow awaken too. We’ve got God the artist and the standup comic. God laughs, God creates, God peeks through randomly.

But can any of these Gods save? Can any of these theologies account for babies being tossed into the flames?

In a word, no.

As we continue to call out into the void, from time to time we can hear something faint coming back. Sometimes the Joban call is answered. Sometimes, inexplicably, the Universe listens.

In the end, we are left with unrelenting questions, and no true answers. While the Torah of Auschwitz might give us glimpses of the artist-formally-known-as-God, the focus always returns to us. We can never prove whether God is best understood as a shadowy artist, a stand-up comic, a life force within us or the corona of an eclipsed heavenly orb.

And so, you might ask, how can we believe in a God so capricious as to allow millions to die in gas chambers and yet align stars to help a baseball team?

But despite all evidence to the contrary, Elie Wiesel, the great prophet of the Torah of Auschwitz, the one who will be recalled as long as Jeremiah and who had every reason to succumb to despair, said this in a 2006 interview with Time:

“(Albert) Camus said, ‘Where there is no hope, one must invent hope.’ It is only pessimistic if you stop with the first half of the sentence and just say, There is no hope. Like Camus, even when it seems hopeless, I invent reasons to hope.”

We cling to hope and invent reasons to hope, if not for some manifestation of a traditional God, than at least for a notion of Ultimate Justice; because we desperately need the moral foundation laid out at Sinai. In that sense, we need God because no human being should ever be allowed to usurp that divine role. We need God to prevent extremists from perverting religious imagery to horrific ends. But should God tarry, we need the courage to take matters into our own hands and bring justice to our world.

If Heschel were alive to see Elon Musk’s antics this week, which go way beyond is now infamous sieg heil, I think he’d be thrown right back to the crying! Thankfully the ADL has seen the error of its ways. Maybe because they realized that Musk was laughing at them - and at all Jews. See also Saturday’s beut: Elon Musk tells far-right AfD rally there’s ‘too much focus on past guilt’ in Germany. Which caused me to wonder: Is Trump planning a blanket pardon of the Third Reich?

The end of the seven day mourning period (“shiva” means seven) depends on several factors, but assuming that the burial takes place in a traditional manner, as soon after the death as possible, say, one day after the loved one’s passing, shiva would end on the 8th day after the death, the 7th after burial.

Read and listen to my 2017 High Holiday sermon cycle that introduced the concept of a Torah of Auschwitz and led to my book. See also a digest of “mitzvot from the Torah of Auschwitz” in my discussion guide to the book.

I sent back daily dispatches when I accompanied a March of the Living group in 2010. What they might lack in polish they make up for in a sense of immediacyand our adventure unfolded, with more unexpected twists and turns than the Holocaust Tour of the current film, A Real Pain. Daily links are below. Photo Album 1, Album 2, Album 3, Album 4

This was written before the most recent revelations about Woody Allen became known - I still feel it valid to include it, though with some trepidation.

My son Ethan, 13 at the time, was ready to give up on God altogether if the Sox were swept by the Yankees. Evidently God was listening. See the article I wrote about it.

I'll reply, Sharon, because comparing current events to the Holocaust is a radical distortion of history on so many levels. Saying "Jews" here in itself is proof that, in this form, anti-Zionism is in fact a form of antisemitism. Otherwise, since I do not want to run away from these accusations but rather face them head-on (just as I have never hesitated to criticize some actions of the Israeli government head-on), I want to share an article from the American Jewish Committee that takes this on directly and persuasively. I share it here but please understand that I do not wish to dignify these accusations by continuing a debate on this topic in this space. I'll be happy to address anything privately and do hope you'll continue to read my posts. But - for you and others - please do not echo these grotesque comparisons in this space. One reason I wrote today's post, in fact, is because many people loosely throw around the term "Holocaust" without really knowing what happened. Holocaust education is an important priority of mine, and I do thank youn for enabling me to clarify one of the key reasons why. Here's the article: 5 Reasons Why the Events in Gaza Are Not “Genocide” - https://www.ajc.org/news/5-reasons-why-the-events-in-gaza-are-not-genocide